By Sven Mikulec

We’ve always found the tagline of George Lucas’ American Graffiti, the nostalgic story of being young and innocent in a small Mid-Western American town, to be a bit curious. Why did Lucas and his people choose the words “where were you in ’62” if the movie came out in 1973? Only 11 years had passed, what happened within that specific time frame to make ’62 seem like forgotten history? Why is the year significant, what events might have happened for the year to stand out like that? The answer is: nothing happened. But the events that followed it changed America and the world forever, and in collective memory of the American people 1962 remained a peaceful, innocent, untarnished time they could look back at with love, nostalgia and sorrow in their hearts. On a dreadful November afternoon in 1963, President Kennedy was assassinated during the infamous Dallas motorcade, which also signified the loss of all hope that the United States would pull out of Vietnam. The bloody conflict in the Far East continued, the government continued to spend billions of dollars to finance a military confrontation doomed to fail from the very get-go, Americans continued to come back to their families in wooden boxes. In ’68, the murders of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Bobby Kennedy further traumatized the American society. The Civil Rights Movement, the sexual revolution, women’s liberation… American culture experienced a shock, the confidence of the people in their democratically elected leaders started to crumble down in fear, anger and paranoia, the society suffered from disintegration and division, and every single person lost their innocence and was faced with the harsh circumstances of political and social turmoil that made ’62 seem a few centuries away.

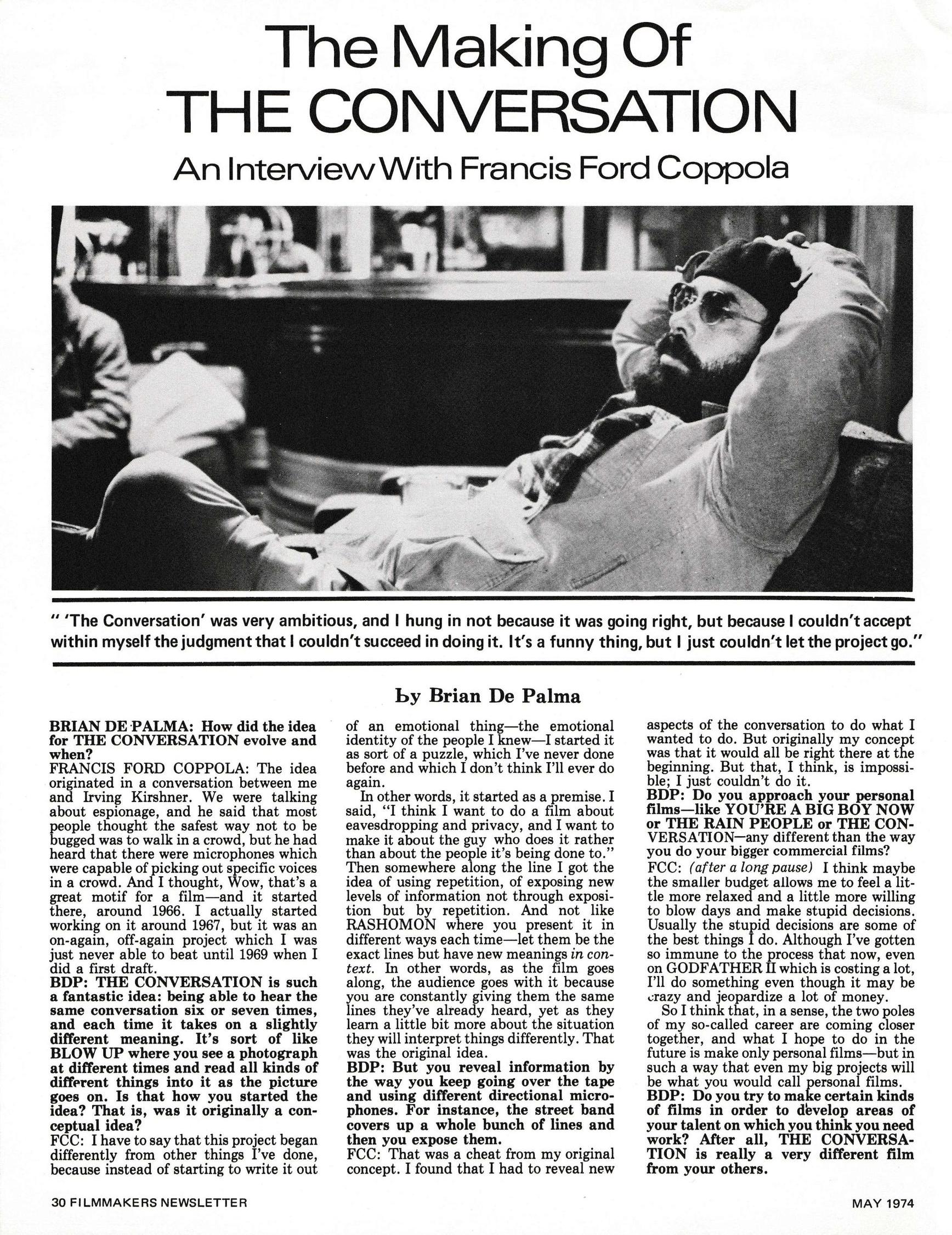

It is this feeling that Lucas’ film emulates so well. Semi-autobiographical and openly sentimental, American Graffiti is the love letter that Lucas wrote to his youth, as well as to the youths of millions of his compatriots. For all of us who didn’t have the chance to get drunk, ride around and chase girls in the lazy evenings in small towns around the States, American Graffiti is a historical document, a piece of fiction powerful enough to bring to life the emotional state of naive youth before the traumatic shitstorms of the 1960s started to take place. Written by George Lucas, Gloria Katz and Willard Huyck, produced by the great Francis Ford Coppola, starring an group of actors who would build their careers in the years that immediately followed the release of this film, American Graffiti is a cinematic endeavor whose strength and significance greatly surpassed the simple fact that the project helped Lucas finance his Star Wars dream come true. It was a box office hit, sure, but the memory of its financially impressive numbers fade away, while the nostalgic sentiment and the visible love and passion Lucas poured into this project remain. American Graffiti is a monumental film for American history and culture.

A monumentally important screenplay. Screenwriter must-read: George Lucas, Gloria Katz & Willard Huyck’s screenplay for American Graffiti [PDF]. (NOTE: For educational and research purposes only). The DVD/Blu-ray of the film is available at Amazon and other online retailers. Absolutely our highest recommendation.

Loading...

Loading...

George Lucas Interview, Academy of Achievement.

When I was doing American Graffiti I was still struggling with my ‘I don’t want to be a writer’ syndrome. I had some good friends of mine that I wanted to write the screenplay, but it took me like two years just to get the money to do a screenplay. And I got a little tiny amount of money and—which I had to go actually to the Cannes Film Festival to get on my own. So finally I got this money. I called back and I said, you know, “I got the money. We can start working on the screenplay.” And they said, “Oh, we don’t want to do that now. We’ve got our own low-budget picture off the ground and we can’t write it.” I said, “Oh no.” I said, “What am I going to do? I am in Europe and I’m not going to be back for like three months and I want to get this thing off the ground.” So they recommended another student from school that I knew pretty well. I had a story treatment that laid out the entire story scene by scene, so I called him over the phone from London and I said, “Do you want to do this?” And he said, “Okay.” The person I was working with at that time as a producer made a deal with him for the whole money because there wasn’t very much. It was so tiny that he could only get him to do it for the whole amount of money. When I came back from England, the screenplay was a completely different screenplay from the story treatment. It was more like Hot Rods to Hell. It was very fantasy-like, with playing chicken and things that kids didn’t really do. I wanted something that was more like the way I grew up. So I took that and I said, “Okay. Now here I am. I’ve got a deal to turn in a screenplay. I’ve got a screenplay that is just not the kind of screenplay I want at all and I have no money.” And, I spent the very last money I had saved up to go to Europe to make the deal, so I had nothing. That was a very dark period for me so I sat down myself and wrote the screenplay.

After I did American Graffiti, and it was successful, it was a big moment for me because I really did sit down with myself and say, “Okay, now I am a director. Now I know I can get a job. I can work in this industry, and apply my trade, and express my ideas on things and be creative in a way that I enjoy. Even if I end up doing TV commercials or something, or I fall back into what I really love is documentaries. I’ll be able to do it. I know I can get a job somewhere. I know I can raise money somewhere. I know I can do what I want to do.” That was a very good feeling. At that point, I’d made it. There wasn’t anything in my life that was going to stop me from making movies. —George Lucas Interview, Academy of Achievement

“This is a very informative documentary that features many interviews and other footage of the cast and crew for the film. Any true fan of the film should be thrilled with what is offered to watch here. This clocks in at 78 minutes, more than enough time to explain many aspects of the film, from Lucas’ first conception to it’s theatrical release.” —Rhyl Donnelly/IMDb

George Lucas discusses the making of his film American Graffiti; how the film affected audiences in the early 1970’s, and about his friendship and working relationship with Francis Ford Coppola.

A Legacy of Filmmakers: The Early Years of American Zoetrope, narrated by Richard Dreyfuss, illuminates the creation of Francis Ford Coppola’s landmark San Francisco film company American Zoetrope, set against the changing landscape of American cinema in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

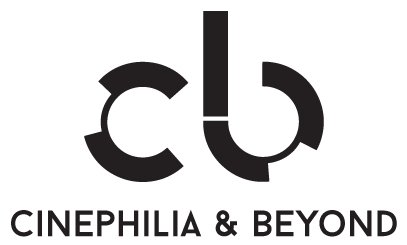

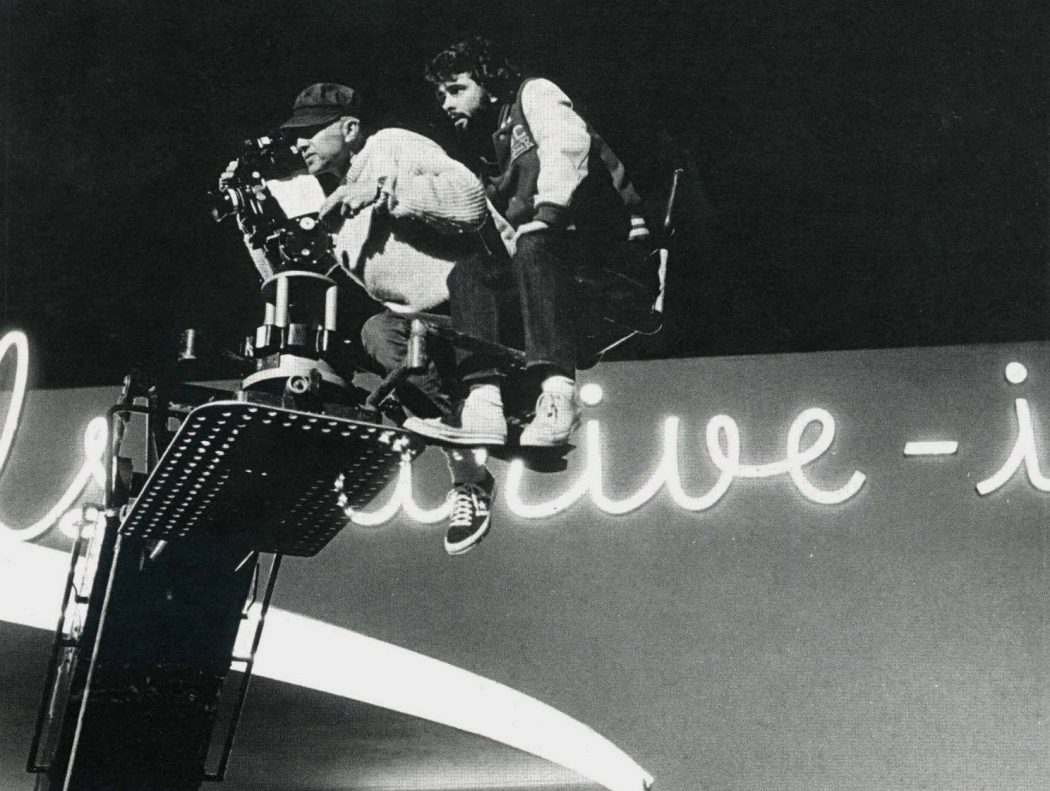

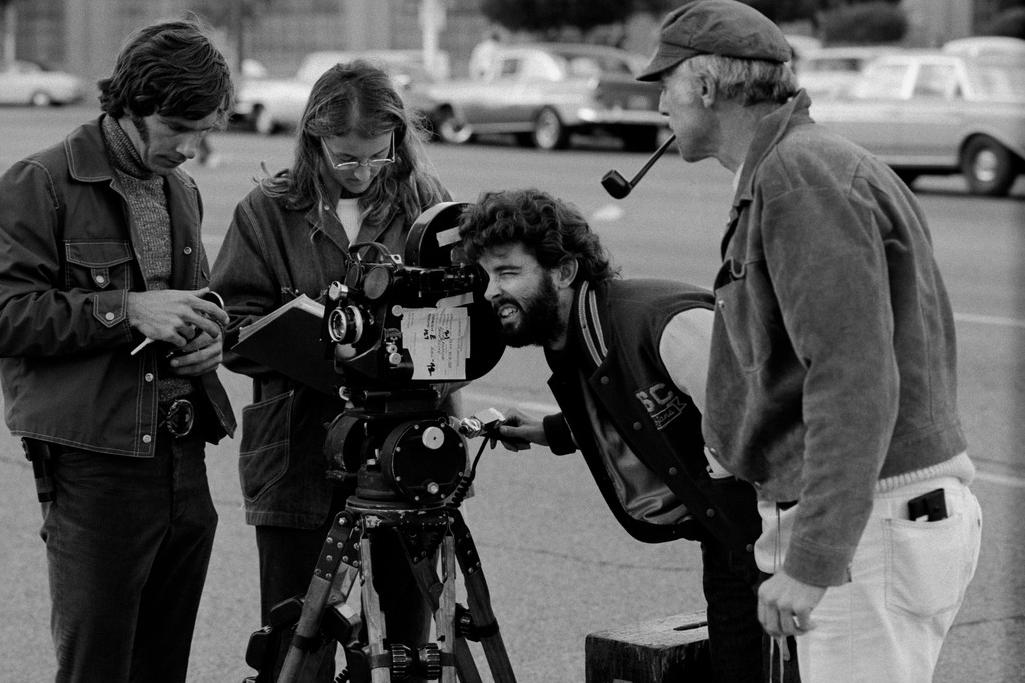

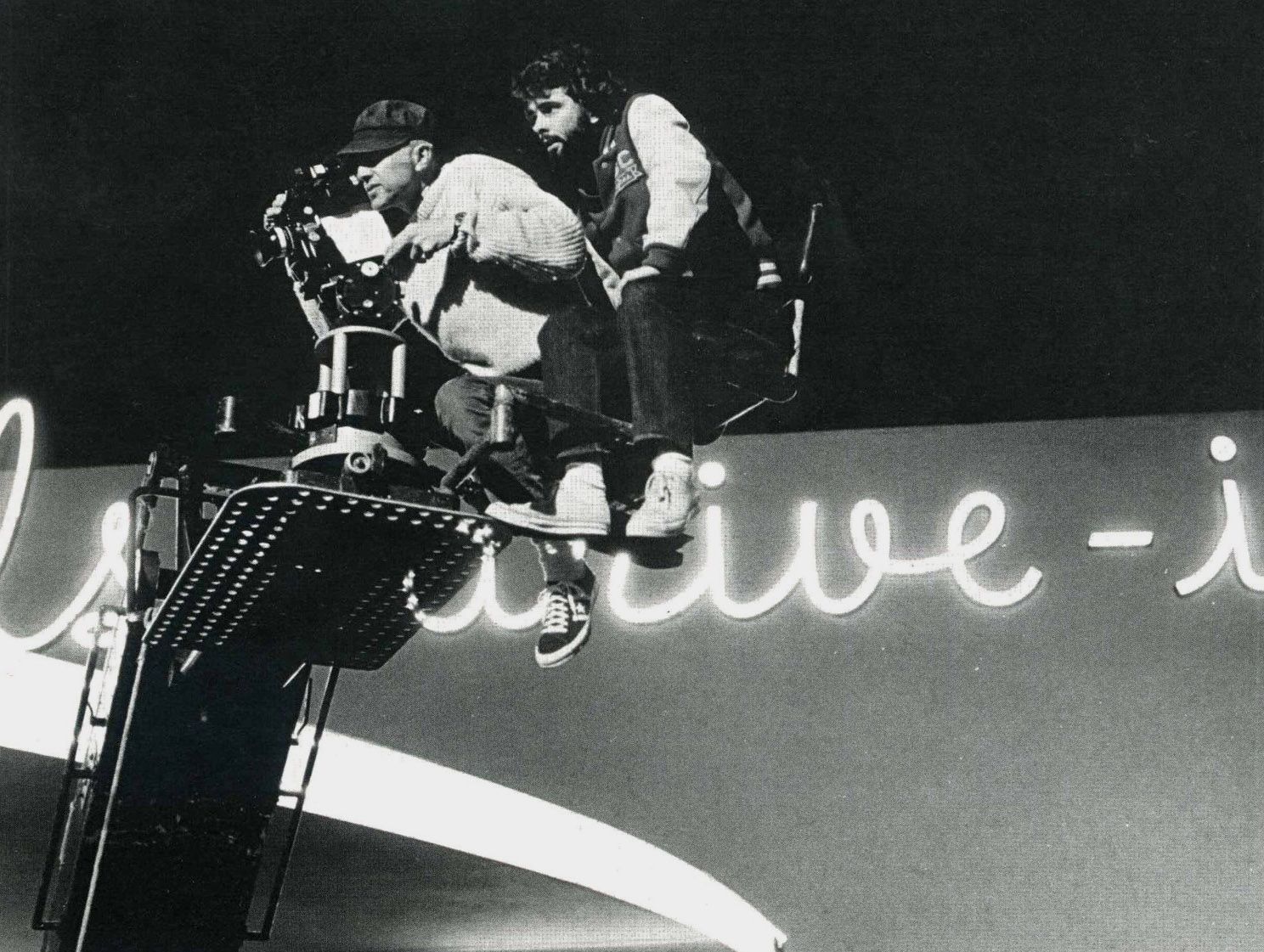

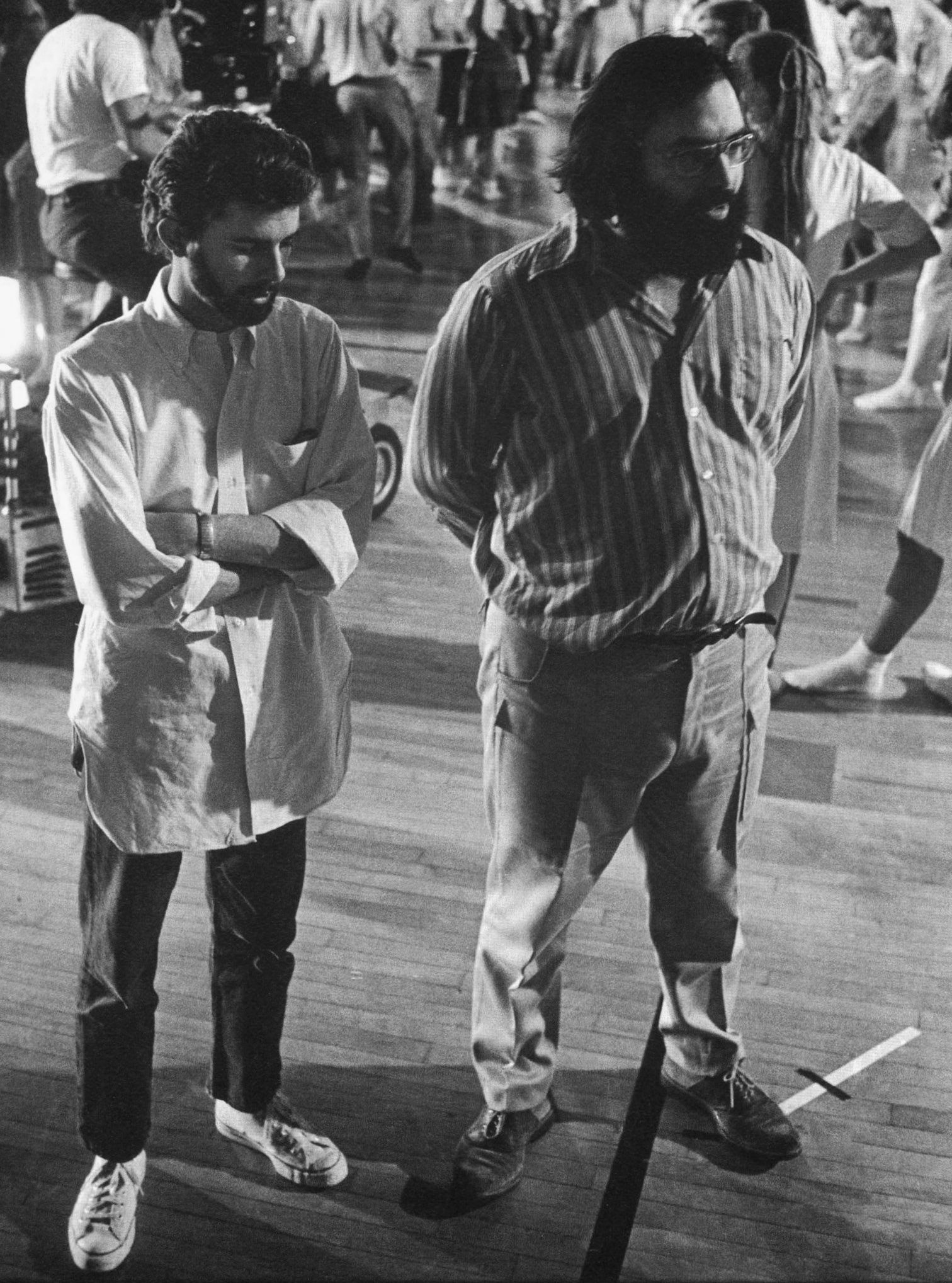

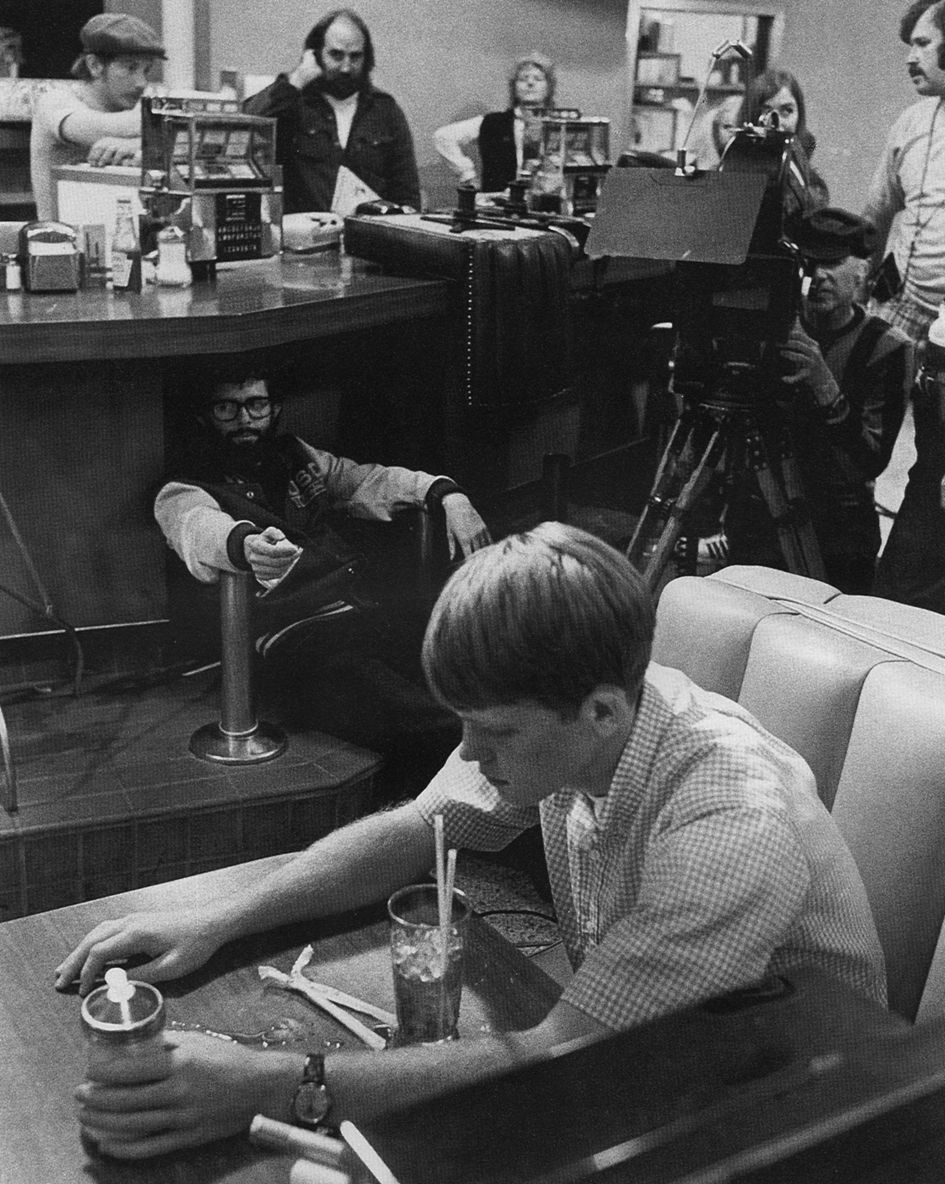

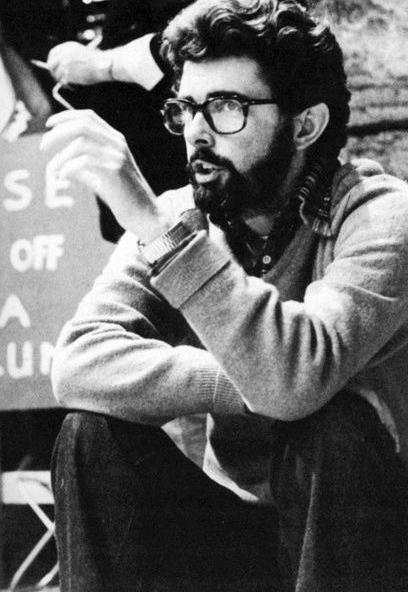

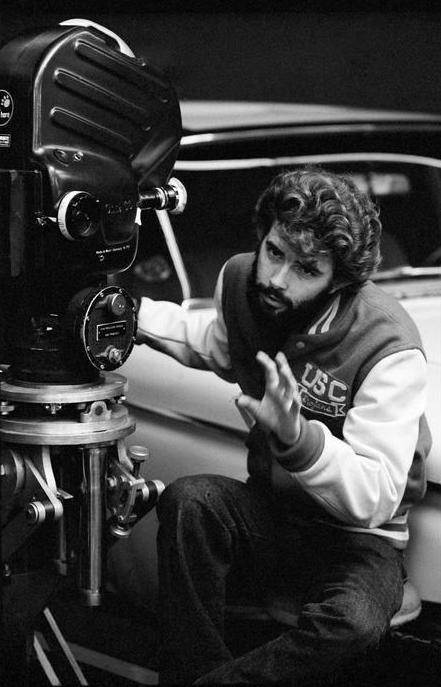

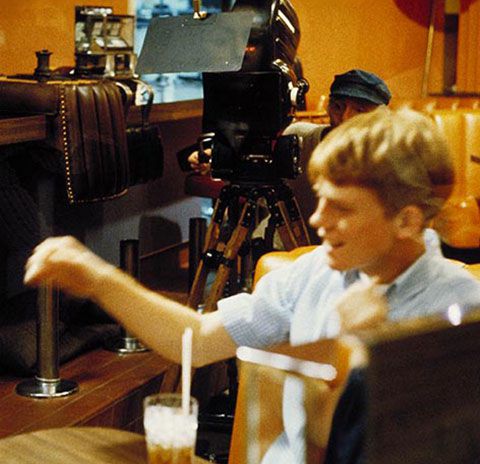

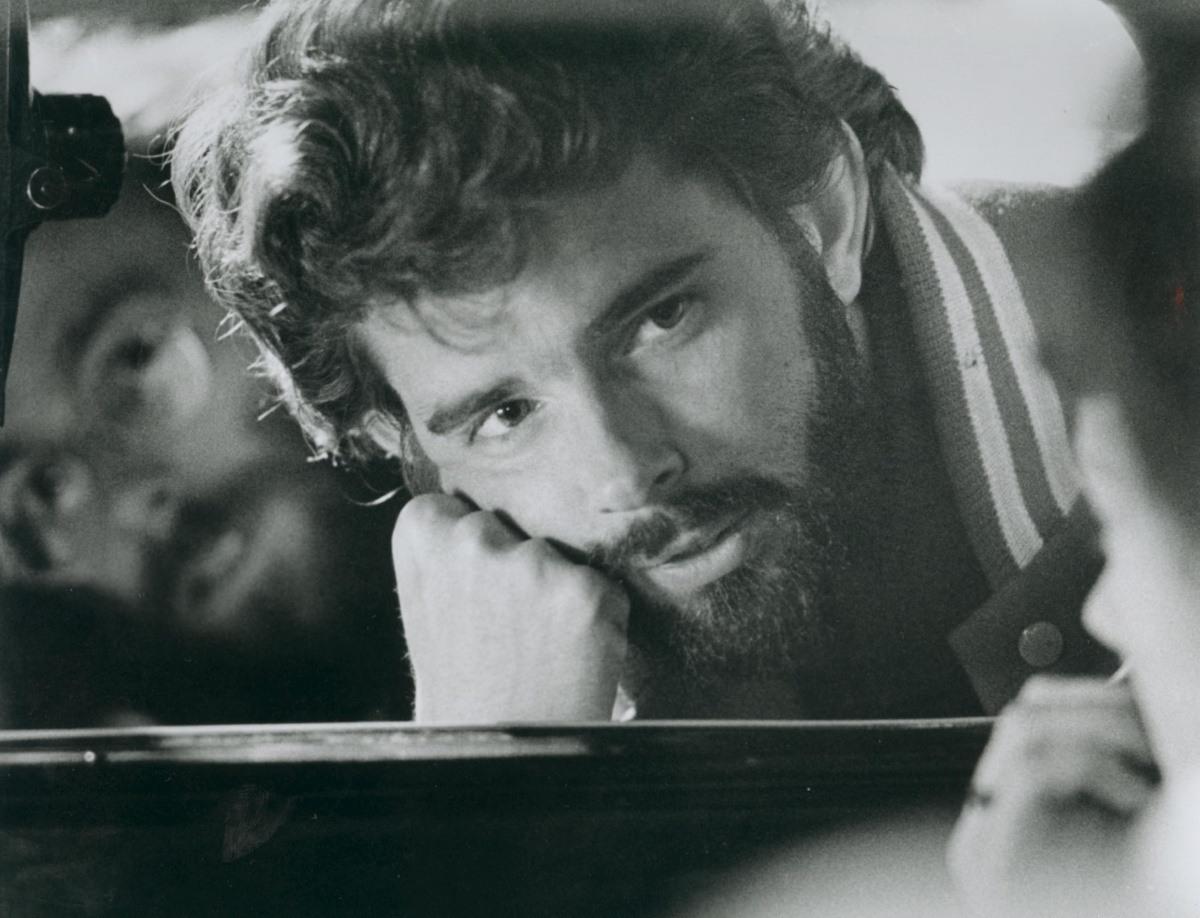

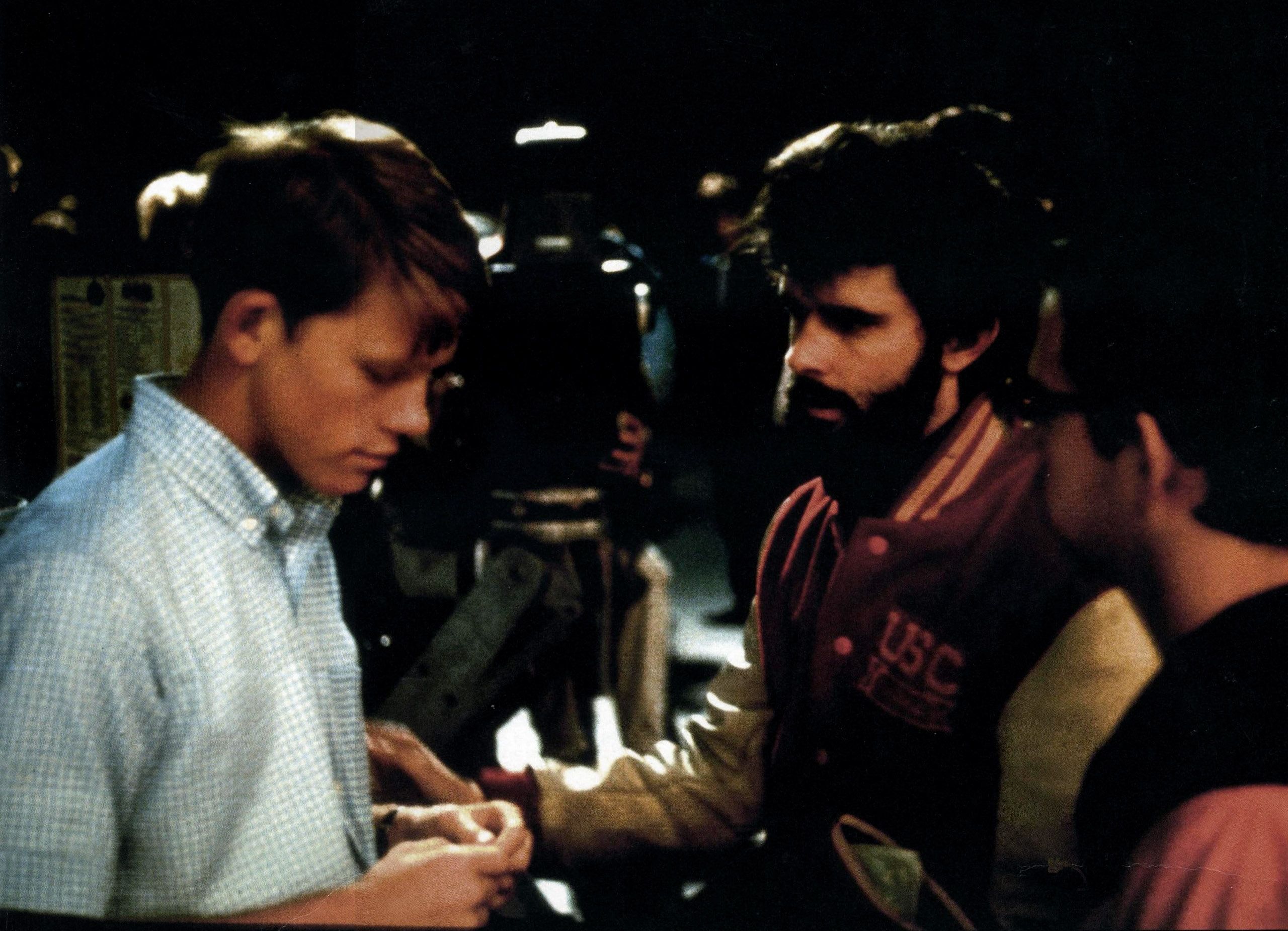

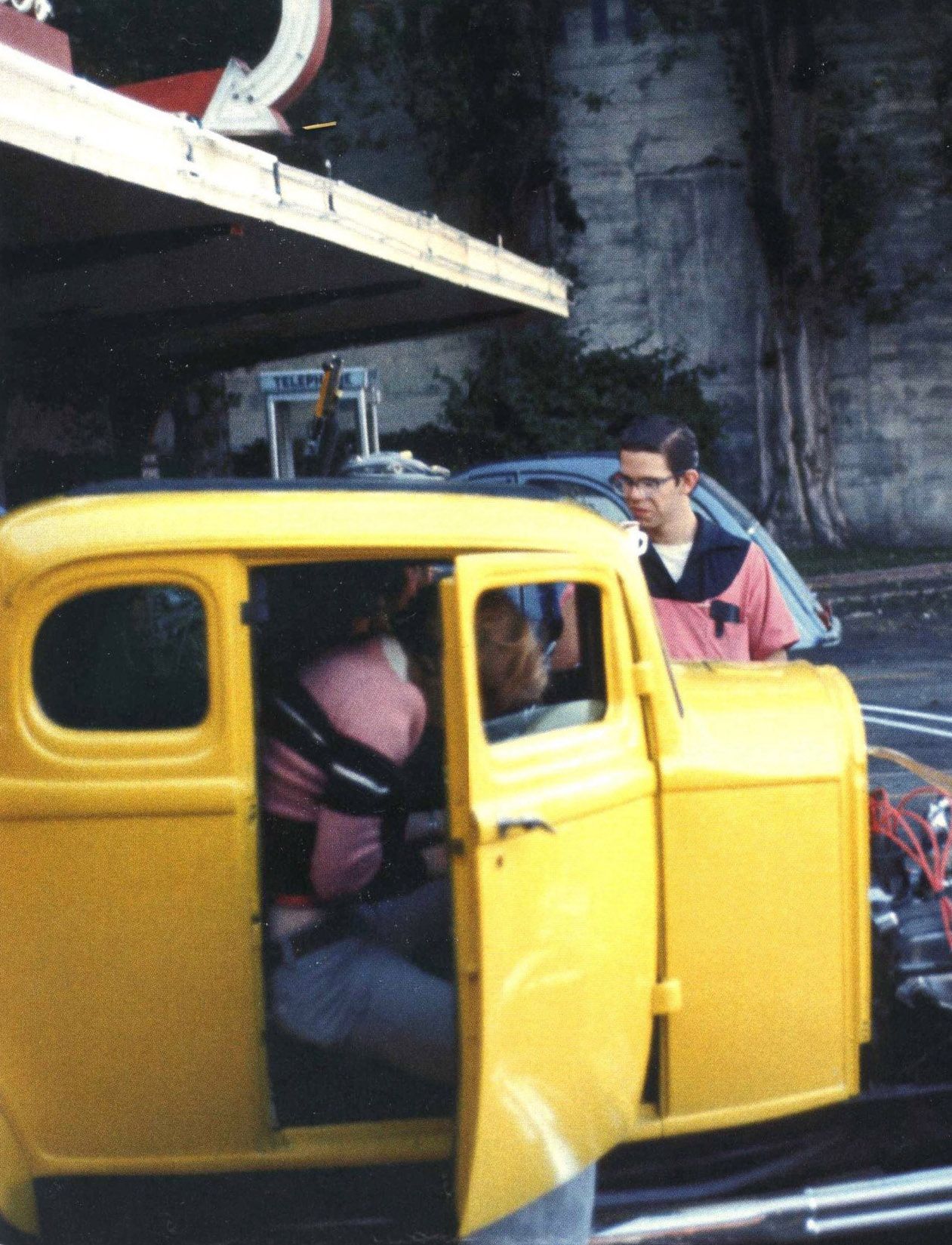

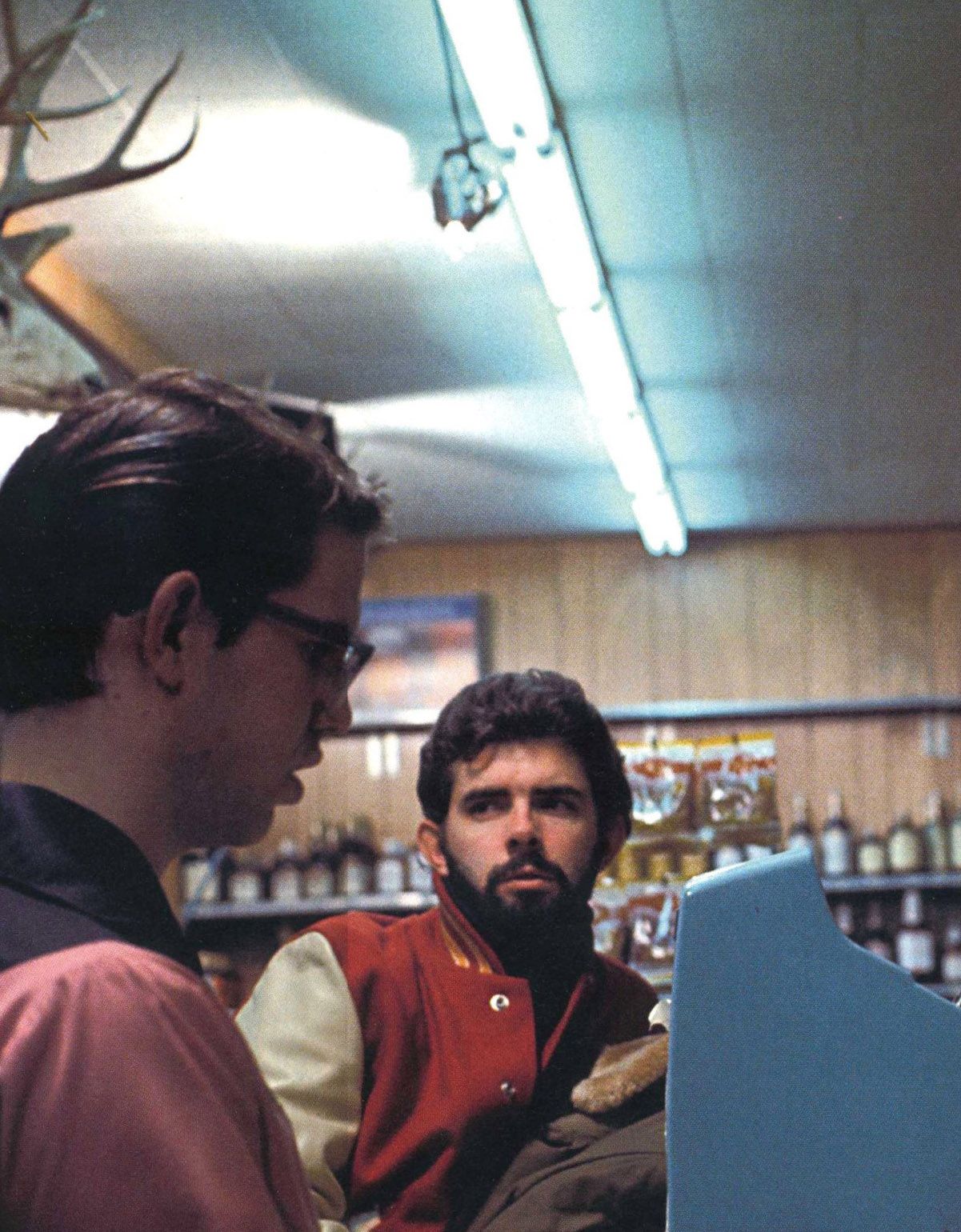

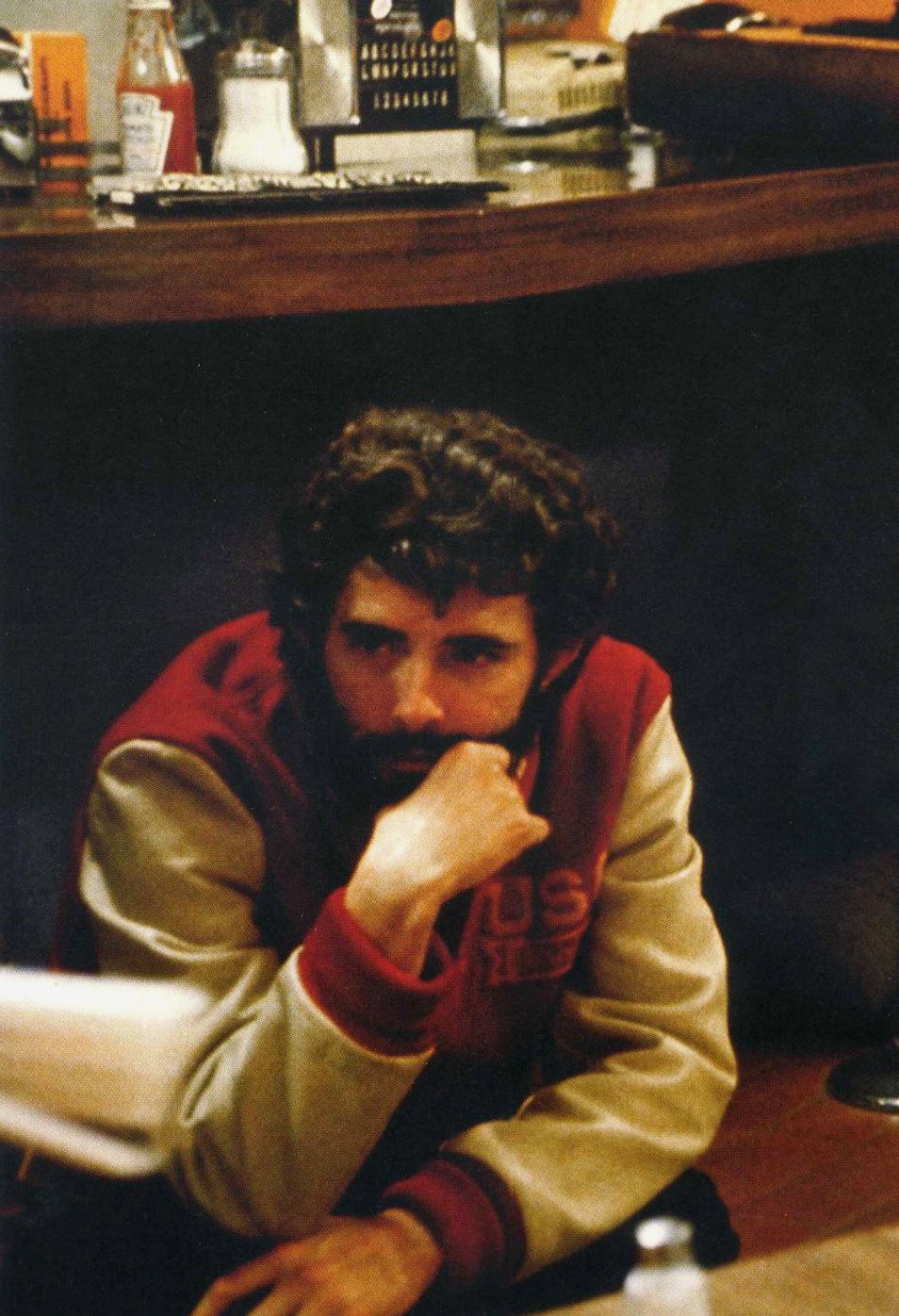

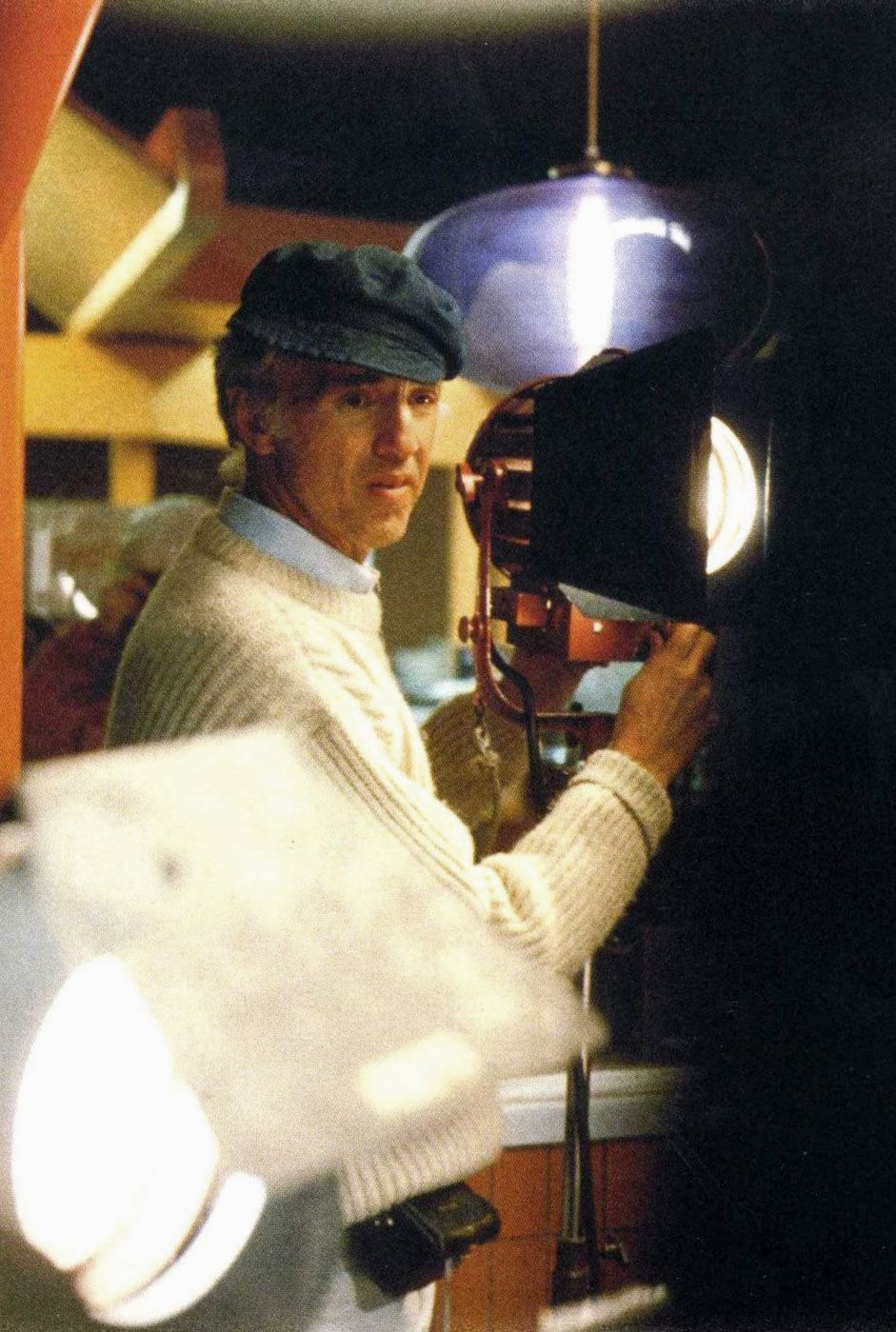

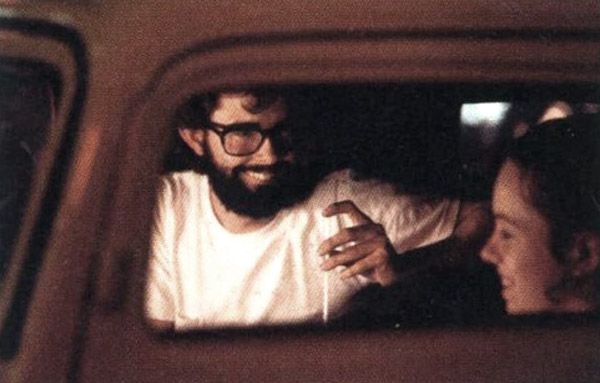

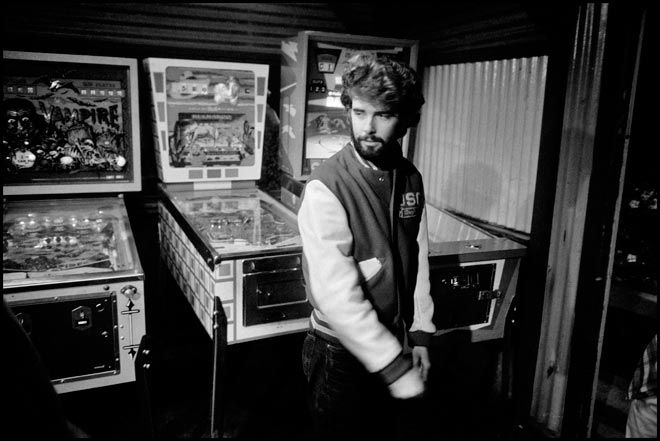

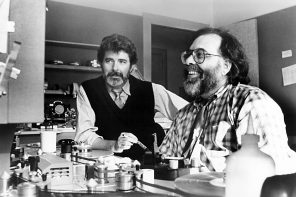

Here are several photos taken behind-the-scenes during production of George Lucas’ American Graffiti. Photographed by Paul Ryan & Dennis Stock (Magnum Photos) © Lucasfilm Ltd. Intended for editorial use only. All material for educational and noncommercial purposes only.

We’re running out of money and patience with being underfunded. If you find Cinephilia & Beyond useful and inspiring, please consider making a small donation. Your generosity preserves film knowledge for future generations. To donate, please visit our donation page, or click on the icon below:

Get Cinephilia & Beyond in your inbox by signing in

[newsletter]