By Sven Mikulec

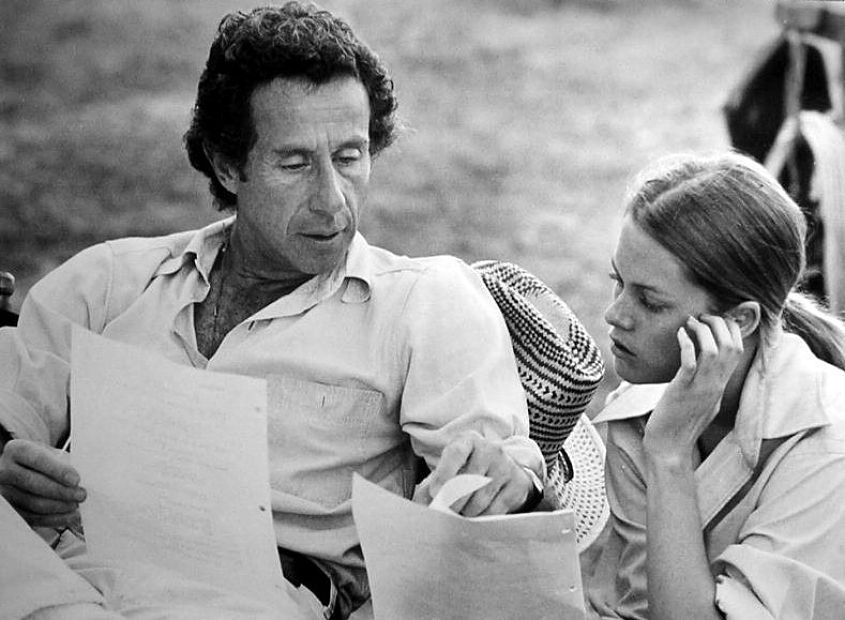

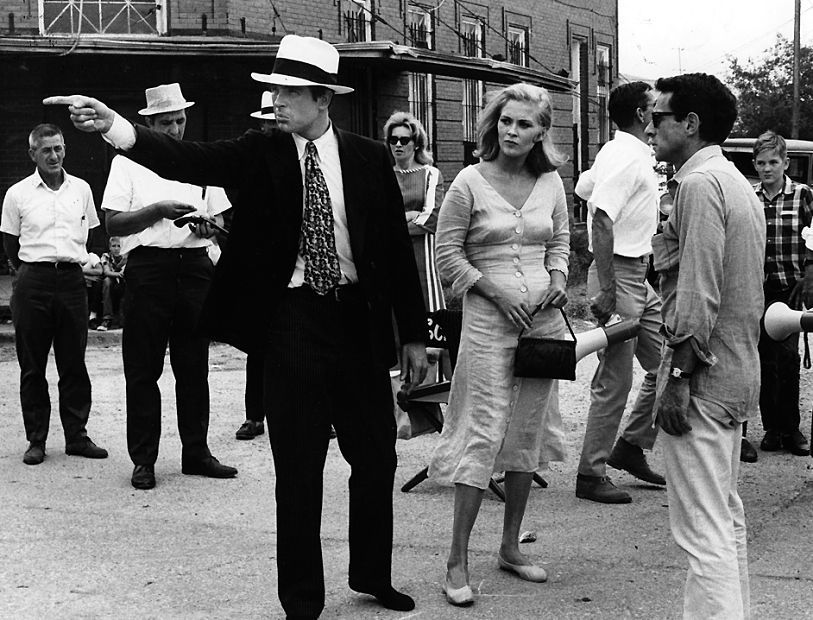

Whenever Arthur Penn’s name is mentioned, most people probably think of Bonnie and Clyde. The Beatty-Dunaway biographical crime film perhaps remains the most critically acclaimed part of the director’s resume, but a lot of people still remember his somewhat less flashy, slightly puzzling and definitely more intriguing noir called Night Moves, labeled by some as one of the best films you’ve never seen. The story of a private detective hired to find a missing teenager, struggling to understand the overwhelming, seemingly unconnected events around him, crippled by his limited knowledge and old-school methods that rarely bring him any closer to his goal, is a wonderfully shaped little thriller carried on the shoulders of fantastic Gene Hackman and a cunningly staged comment on the post-Watergate paranoia and despair of the American society.

Every frame is riddled with loneliness, frustration and anxiety, while the protagonist serves as an almost complete opposite of all those ingenious private eyes we’d seen in classic film noir. Hackman’s Harry Moseby is no Sam Spade or Philip Marlowe: he’s devoted but confused, definitely not in charge of events that unfold in front of his usually oblivious eyes. He’s a paper boat in a pool full of enthusiastic children, impotently watching the waves swerving him from one side to the other. The audience is just as bewildered as Harry: Alan Sharp’s aptly written screenplay makes sure of that. Night Moves demands, and deserves, multiple viewings, and every single one of them is equally rewarding.

A monumentally important screenplay. Screenwriter must-read: Alan Sharp’s screenplay for Night Moves [PDF]. (NOTE: For educational and research purposes only). New 2017 1080p HD remaster created from 4K scan from the original camera negative is available at Warner Archive Collection and other online retailers. Absolutely our highest recommendation.

Loading...

Loading...

Moral ambiguity, mixed motives, irony and sex. According to Scottish screenwriter Alan Sharp, these are the ingredients a story needs to make a decent screenplay. ‘All the things I’ve written are pastiche, and I get work because I’m a reliable craftsman. It’s like being a plumber: you come in, do a tidy job, and you’re not a prick to deal with, so people hire you again.’ Others had a far higher opinion of Sharp’s achievements. British film critic Trevor Johnston, declared him ‘Britain’s greatest living screenwriter,’ a man so gifted that his first five scripts were filmed back-to-back during the early 70s. —Screenwriter was one of ours

Sharp was very clear about his role as a writer. ‘I’ve no desire to be a producer,’ he said, ‘I have no skill in raising bucks’ and when asked whether he would change anything about his career so far he replied no, not a thing. ‘For writers just starting out, I would ask, ‘Do you like writing?’ If the answer is yes, I then say ‘just write, as much as you can’. It’s an excellent notion to get some wheels on your chariot. If there’s a story you like, just write it up and see how it feels. It’s not illegal until you do something with it.’ Sharp said he can write screenplays with relative speed, as compared to a novel, adding that there are not that many people writing totally original material. ‘You may as well copy,’ he said. He enjoys writing but admitted there are times when the writing process can be a real grind and offered a word of advice—‘persevere.’ —Writer’s Room: Alan Sharp

Night Moves Revisited: Scriptwriter Alan Sharp Interviewed by Bruce Horsfield, December 1979, Film Quarterly, Vol. 11, No. 2, 1983. Thanks to Eugene.

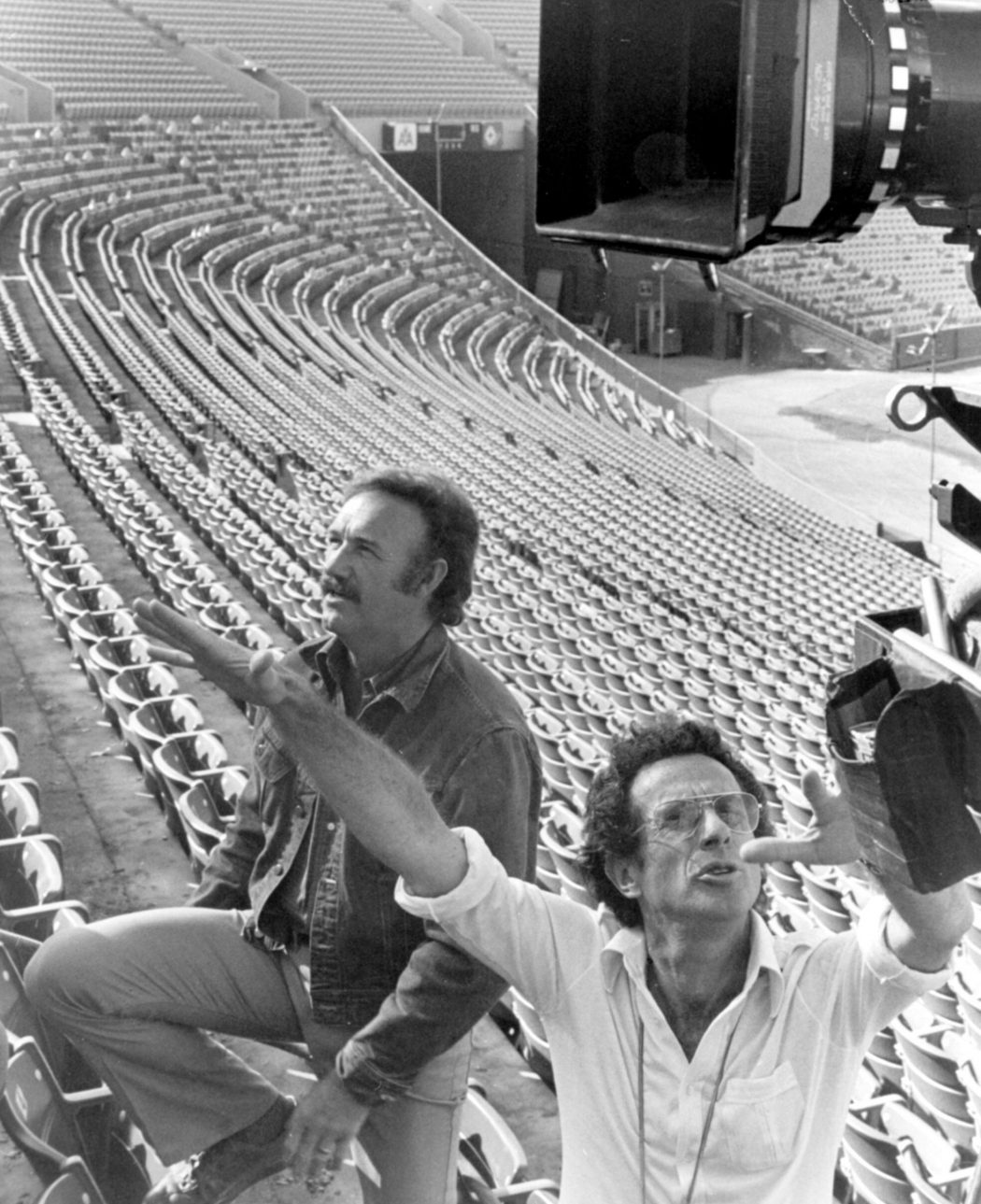

The importance of a singular, guiding vision: an interview with Arthur Penn by Gary Crowdus and Richard Porton.

Another characteristic of your work is the subversion of traditional genre expectations, such as in Night Moves. That film seems to have some parallels with Blowup because both films deal with the elusiveness of the truth. The Harry Moseby character, like David Hemmings’s character in Blowup, is never really sure of what the truth is.

Penn: I hadn’t thought of that, but it’s perfectly acceptable. I think we were trying to do something just a little more than that, which was to say that in the detective film genre, the detective eventually solved the crime. I mean, Bogart eventually found it out, however painful it was, and Mary Astor was sent up. In Night Moves we were trying to say, “Wait a minute, maybe the enemy is us. Maybe Moseby’s vision is blocked by his need to have a friendship with this stunt man, who was taking advantage of that friendship.” That was the only other sort of quietly psychological aspect that we were adding to that form. It’s a pretty dark and despairing film, and I guess I was feeling that way.The paranoia links the film to Mickey One in a way.

Penn: Yeah, maybe, but it was much darker than Mickey One, which had a kind of youthful hope. In this film, when someone asked, “Where were you when Kennedy was shot?,” the reply was, “Which Kennedy?” That was really the capsule of our lives at that point.There are echoes of the Kennedy assassination in the enormous conspiracy that devolves toward the end of the film.

Penn: Yeah, and, you know, I had worked with both Kennedys. I had served as a TV advisor to Jack Kennedy’s campaign. During the Nixon‑Kennedy debates we were in the Kennedy camp using the medium in a way we thought made for a better presentation. Later I started working with Bobby. I went down to Washington and we did one radio commercial. We were then going to do a whole bunch of radio and TV stuff as soon as he came back from California, and of course he never did.So Night Moves was a very personal film?

Penn: It was personal in that respect, but it’s also despairing in that I just felt, “Oh God, this country…” I mean, those assassinations—Jack Kennedy, Bobby Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Jr.—were just crushing to people who’d been involved in those movements. I’d been in the Civil Rights movement up to my ears.Dede Allen has described your shooting method as one of providing “top to bottom editorial coverage.” Would you explain what she means by that?

Penn: Well, it’s lots of coverage, but I don’t shoot that much film in relation to other directors, not by a long shot. I think what Dede is saying is that once the actors and I have rehearsed it and gotten the scene, then I don’t waste any time shooting alternate angles. I cover it tight, tight, tighter, because I believe that for editing to really work you need to have the material to alter the rhythm of a scene. As you know, we shoot out of sequence, for economic reasons. I defy you, no matter how good you are, to know on the second or third Tuesday of the movie what that last scene is really going to be like if you haven’t gotten there yet. You have to give yourself material so that when you’re in the editing room, and you suddenly see the scene, now in context, you don’t have to say, “Oh shit, why didn’t I shoot that?” My first reaction to The Left‑Handed Gun was, “Oh, why didn’t I cover it. I was right there but I didn’t do it. I’d love to be in on Paul Newman’s eyes right now but it can’t be there because I don’t have the shot.” That’s why in The Miracle Worker, when I filmed that long fight scene, I covered it every possible way because I wanted to be able to control the rhythm. You see, that’s a nine-minute scene, so it’s gotta start, it’s gotta pick up tempo, it’s gotta move, it’s gotta pick up hostility, you have to take it up the line, up the line, UP THE LINE, to a point, finally, of capitulation. I can do that in the theater because I see the whole scene in the context of the play but on a movie, in the third week of production, I can’t do it. That’s what I think I brought into Dede’s life because I said, “Dede, we’re just going to have to learn to understand my rhythms, and I’m going to provide a ton of material so that we can really change rhythm from what the scene seemed to be when we read it to when we shot it,” and, by God, that has stood us in good stead.You’ve obviously had a very good working relationship with her.

Penn: Dede’s a first‑rate editor, she’s made an awful lot of mediocre directors look very good. She brings a wisdom and dedication to it that almost nobody else I know has. She’s a nut when it comes to the editing process. She’s tenacious, she won’t quit, and she finds solutions. Look at all the people she’s trained—Steve Rotter, Jerry Greenberg, Richie Marks—they’re the prominent editors of our time. All the Academy Awards go to people who trained with Dede, but she never got one. —An interview with Arthur Penn

Penn was a critic of commercial filmmaking from the outset. Presciently, he told the French film magazine Cahiers du Cinéma in 1963, about Hollywood: “As far as I can see, the place is killing itself. Pretty soon it’ll be churning out only blockbusters and TV series. That’s all, no more actual films. Eventually the corporations turning out forty or fifty films a year will make only four or five.” In an address to students at Dartmouth College in 1968, Penn disparaged the “structured clichés” accepted as the “norm” in studio films—“a norm,” he added, “that on the very first day I stepped onto a film set I found myself in opposition to.” To an interviewer in 2004, Penn commented that the Hollywood studios had “become small parts of huge corporations, and all they are really interested in is showing a profit, and consequently, profit in their terms means a film which can play all around the world, which means, essentially, a film not being dialogue-dependent, and therefore, you get non-people, and that’s why we have things like Shrek [the animated film]—which is marvelous for what it is, but it tends to take the place of doing films. And I don’t think many films of the future of any major significance are going to come out of there.” —Arthur Penn, American filmmaker (1922-2010) by David Walsh

In Memory of Arthur Penn (1922–2010) & Alan Sharp (1934–2013)

If you find Cinephilia & Beyond useful and inspiring, please consider making a small donation. Your generosity preserves film knowledge for future generations. To donate, please visit our donation page, or click on the icon below:

Get Cinephilia & Beyond in your inbox by signing in

[newsletter]