By Sven Mikulec

I read an article recently saying that one of the reasons the film has found an ongoing audience is that it was incomplete. That’s absolute horseshit. The film was very specifically designed and is totally complete. In those days, there was more discussion than was welcome, as far as I’m concerned. [Screenwriter] Hampton Fancher, [producer] Michael Deeley, and I talked and talked and talked—every day for eight months. But at the end of the day, there’s a lot of me in this script. That’s what happens, because that’s the kind of director I am. The single hardest thing is getting the bloody thing on paper. Once you’ve got it on paper, the doing is relatively straightforward.—Ridley Scott

Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner’s path to stardom and cultism has hardly been a bump-free ride. Heavily disputed upon its release, often criticized as an occasionally senseless portrayal of a future with a shallow storyline and abundance of plot holes semi-efficiently covered up by admittedly wonderful visuals, this science-fiction masterpiece is still regarded as a strong polarizing factor in discussions among filmlovers, but its status has quite immeasurably improved since its debut in North American theaters back in 1982. Many people had a change of heart regarding its value. Roger Ebert himself first failed to register many of the things that made people love it so damn much, only to change his mind and reevaluate the movie decades later when a special edition was released on its 25th anniversary. But the bottom line is this: whatever a person’s opinion on the qualities or inadequacies of Blade Runner might be—and there are solid arguments convincingly stated from both camps—it’s impossible for a reasonable, art-loving individual not to appreciate Ridley Scott’s movie’s originality, vision and gigantic influence it wielded on films made in the years after the iconic Rick Deckard returned to his retirement.

Written by Hampton Fancher and David Webb Peoples, adapted from Philip K. Dick’s 1968 novel ‘Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?,’ Blade Runner tells a story set in then distant future: it’s 2019, Los Angeles, and an ex-detective Deckard is called back from retirement to hunt down six replicants who escaped from one of Earth’s colonies and sought refuge somewhere among us. It’s this dystopian look at the future, rich in detail, strong in emotion, that served as inspiration to many other filmmakers in their subsequent attempts to portray the dark years ahead of us. Huge global corporations are running the show. The cities are overcrowded, filled with homeless or extremely poor people unable to procure bread for the table. Nature is withering, technological advancement is top priority, people are dehumanized, everything’s cold, dark and hopeless. And, yes, it’s raining all the time. Scott created a world like no other, and within it set an exciting and intriguing story full of ambiguity, uncertainty and despair. The protagonist, a man we can relate to and empathize with, is a mystery himself. Blade Runner is a dystopian neo-noir with breathtaking imagery, but supported by a narrative wonderfully, almost poetically written and inspiringly brought to life by acting performances from Harrison Ford, Rutger Hauer and Sean Young.

“Pauline Kael spent three pages destroying Blade Runner and me. Even to the fact that I had a beard. I couldn’t believe it, it was personal. I never met her in my life and it was really distressing.” Scott shakes his head, July 1982 suddenly seeming like a couple of hours ago—though, to be fair to Kael, reading her review now, while she clearly didn’t like the film, she kept any opinions she had on Scott’s facial hair to herself. “But after that moment, I never, ever read press again,” he continues. “Even if it’s glowing, best not read it, because you think you own the world. If it’s killer, best not read it because you think you’ve failed. You have to be your own critic.” —Ridley Scott

Ridley Scott’s vision, craft and use of special effects have passed the test of time. Still equally captivating, still as magical as it was when we first saw it as kids, Blade Runner is a game-changing science-fiction classic that deservedly entered film history books and is there to stay. And all the criticism will be lost in time. Like tears in rain. Time to watch it again.

A monumentally important screenplay. Screenwriter must-read: Hampton Fancher & David Webb Peoples’ screenplay for Blade Runner [PDF1, PDF2]. (NOTE: For educational and research purposes only). The DVD/Blu-ray of the film is available at Amazon and other online retailers. Absolutely our highest recommendation.

Loading...

Loading...

We go further behind the scenes to trace the development of the screenplay from the viewpoint of the two men who, independently of the other, made their contributions to its development. —Starlog Magazine Issue 058

“Everybody in Blade Runner is haunted by mortality, not just the replicants. Initially reluctant, Scott himself only agreed to direct the film after his older brother Frank died of cancer, reasoning it would be a “quick fix emotionally.” In March 1982, Philip K. Dick was felled by a fatal stroke at the age of 53. He never got to see the finished movie. Drenched in death, Blade Runner is a dark vision of the future, but Scott’s definitive Final Cut ends on a cautiously hopeful note. Mortality is inevitable, but before it comes, empathy and trust and love are possible, even between human and android. At the end of his killing spree, Deckard is no longer raging against the machine. Because, deep down, maybe he is the machine.” —Anatomy of a classic

“Released to mixed reviews in 1982, director Ridley Scott’s neo-noir vision of a not-so-distant future where the line between man and machine has all but disappeared went on to cult status and influenced a generation of filmmakers. On the eve of a sequel no one could have predicted, its creative core—Scott, star Harrison Ford, screenwriter Hampton Fancher, and others—tell the story of the original film’s contentious journey to the screen.” —The Battle for Blade Runner

‘BLADE RUNNER’ SOUVENIR MAGAZINE

Ira Friedman worked in the publishing department for Lucasfilm, situated in Los Angeles. He joined in the company in 1980, but soon decided to return home to New York and start his own publishing company. What instigated this move was Lucasfilm’s decision to abandon their L.A. offices and relocate to Northern California. Even though Friedman was invited to come along, he saw an opportunity to pursue his own dreams of publishing magazines. When Lucasfilm’s director of publishing Deborah Call refused to leave the City of Angels and joined forces with Charlie Weber, Lucasfilm’s former president who chose to start a production company, Friedman first heard about this new project they were working on, a film called Blade Runner, and immediately decided to try to get the license for publishing a Blade Runner-themed magazine. “This was the first magazine I had ever published on my own and I put everything I had into ensuring that it turned out to be a prideful piece of work. I made sure it looked good, read well, was widely distributed and publicized,” explains Friedman, calling the project “the result of much passion and hard work.” Like many others, Friedman reasonably expected the movie to be a hit, which would inevitably lead to the popularity of the magazine itself. However, as we all know, Blade Runner was a box office disappointment during its initial run, and Friedman, excited about his first independent venture and proud of the work put into the making of the magazine, was forced to deal with failure. As decades passed, he witnessed the development of Ridley Scott’s film’s cult status and the influence it wielded on countless filmmakers and their stories, while the quality of the magazine itself was never really disputed. With the emergence of the Internet, luckily, nobody is left deprived of the chance to read what Friedman prepared all those years ago.

The Official Collector’s Edition Blade Runner Souvenir Magazine is a wonderful source of information, abounding in great photos and articles; a genuine treat both for hardcore fans of the film and all the newbies who just got introduced to the world of Rick Deckard. There is a lot of fascinating stuff here, but we’re incredibly excited about the interviews with Philip K. Dick, Ridley Scott, Harrison Ford, and Douglas Trumbull. We’re incredibly thankful to webmaster Netrunner from brmovie.com, who put a lot of effort into digitalizing the magazine and even contacted Mr. Friedman to get his blessing for the endeavor. While Netrunner shaped the material by separating photos from the accompanying text, we chose to offer you a .cbr file of greater resolution and quality, so you can browse the content more easily. If we may, we’d like to suggest using a little program called ComicRack for checking out this priceless blast from the past. Enjoy the read!

Future Noir—Blade Runner archives—is a dedication to one of the most incredible cinema pieces in history and to all people who made it. Materials are collected all over internet and many of it from incredibly rich and thorough on-line communities dedicated to Blade Runner, although some items come from a personal archive.

Here is Mark Kermode’s documentary On The Edge Of Blade Runner (directed by Andrew Abbott), produced for Channel 4 in 2000. Features interviews with Ridley Scott, the cast and those who created the humid, sprawling metropolis, the documentary also features previously unseen footage and original special effects test footage and finally reveals the answer to the question whether Deckard is human or replicant.

Future Shocks (27 minutes), is a documentary about Blade Runner from 2003 made by TVOntario (as part of their Film 101 series), has interviews with executive producer Bud Yorkin, Syd Mead, and the cast along with Sean Young, but again without Harrison Ford. There is extensive commentary by science fiction author Robert J. Sawyer and film critics as the documentary focuses on the themes, visual impact and influence of the film. Olmos goes into Ford’s participation and personal experiences during filming are related by Young, Walsh, Cassidy and Sanderson. They also relate a story where crew members created t-shirts which took pot shots at Scott. The versions of the film are critiqued and how closely Blade Runner predicted the future is discussed.

These were taken on the last night of shooting (which was a 36 hour shift for the entire crew according to production executive Katy Haber) on July 9, 1981. Harrison looks exhausted, but maybe a little relieved that the long and dreary shoot is nearing its end. After shooting the parts of the scene covered in these photos, they moved on to the tears in rain speech. —Rarely seen photos from Blade Runner

ORIGINAL STORYBOARDS

Set of 7 storyboard books featuring copies of Sherman Labby’s storyboards from Blade Runner. Issued to Doug Trumbull at the beginning of production, these books feature sequences that were never filmed or early versions of sequences that were changed before filming began.

Loading...

THE CINEMATOGRAPHY OF JORDAN CRONENWETH

Jordan Cronenweth, ASC’s photography for Blade Runner, with its strong shafts of light and use of backlighting, immediately evokes images from classic black-and-white movies, and it is no accident that it does. As Cronenweth explains, “Ridley felt the style of photography in Citizen Kane most closely approached the look he wanted for Blade Runner. This included, among other things, high contrast, unusual camera angles and the use of shafts of light.” —Blade Runner: Cronenweth’s Photography

“We used contrast, backlight, smoke, rain and lightning to give the film its personality and moods. The streets were depicted as terribly overcrowded, giving the audience a future time-frame to relate to. We had street scenes just packed with people… like ants. So we made them appear like ants—all the same. They were all the same in the sense that they were all part of the flow. It was like going in circles—like going nowhere. Photographically, we kept them rather colorless.” —Jordan Cronenweth, ASC

Legendary film editor Terry Rawlings talk about his long career and answer questions from the audience. His credits as a sound editor date from 1962–1977, after which he is credited primarily as a film editor. After working with Ridley Scott on Alien, Terry went on to edit film such as Blade Runner, Chariots of Fire, Watership Down and Goldeneye.

“Among the great out-of-print art books of the world is Blade Runner Sketchbook, collecting original production artwork from what is perhaps best designed science fiction film ever. Originally published by Blue Dolphin Enterprises in 1982, the book includes material by Blade Runner conceptual designer Syd Mead as well as Mentor Huebner, Charles Knode, Michael Kaplan and director Ridley Scott himself, whose contributions are drawn in the style of one of the film’s primary visual influences, Moebius. Because physical copies go for hundreds of dollars, Blade Runner Sketchbook has been available online in various bootleg forms for years, but we’ve just become aware of an embeddable version uploaded in October that makes reading this lost gem easier than ever.” —Andy Khouri

Hilarious negative executives notes to Ridley Scott after seeing Blade Runner for the 1st time.

Discussing Blade Runner—Philip K. Dick interview. The interview was made by Paul M. Sammon in 1981 and it was one of many that Paul had with Philip. More about interviews can be found in the Future Noir book, section The Book (pages 8-16).

On the set of Blade Runner—Entertainment Effects Group team filming the close-up of Sean Young’s eye for the Voight Kampff sequence, courtesy of our friends at Future Noir & douglastrumbull.com.

Ridley Scott dissects the scene when replicant Rachel meets Deckard.

One of the Blade Runner Convention Reels featuring interviews with Ridley Scott, Syd Mead and Douglas Trumbull about making Blade Runner universe. This 16 mm featurette, made by M. K. Productions in 1982, is specifically designed to circulate through the country’s various horror, fantasy and science fiction conventions.

Evan Puschak’s excellent video essay: Listening To Blade Runner.

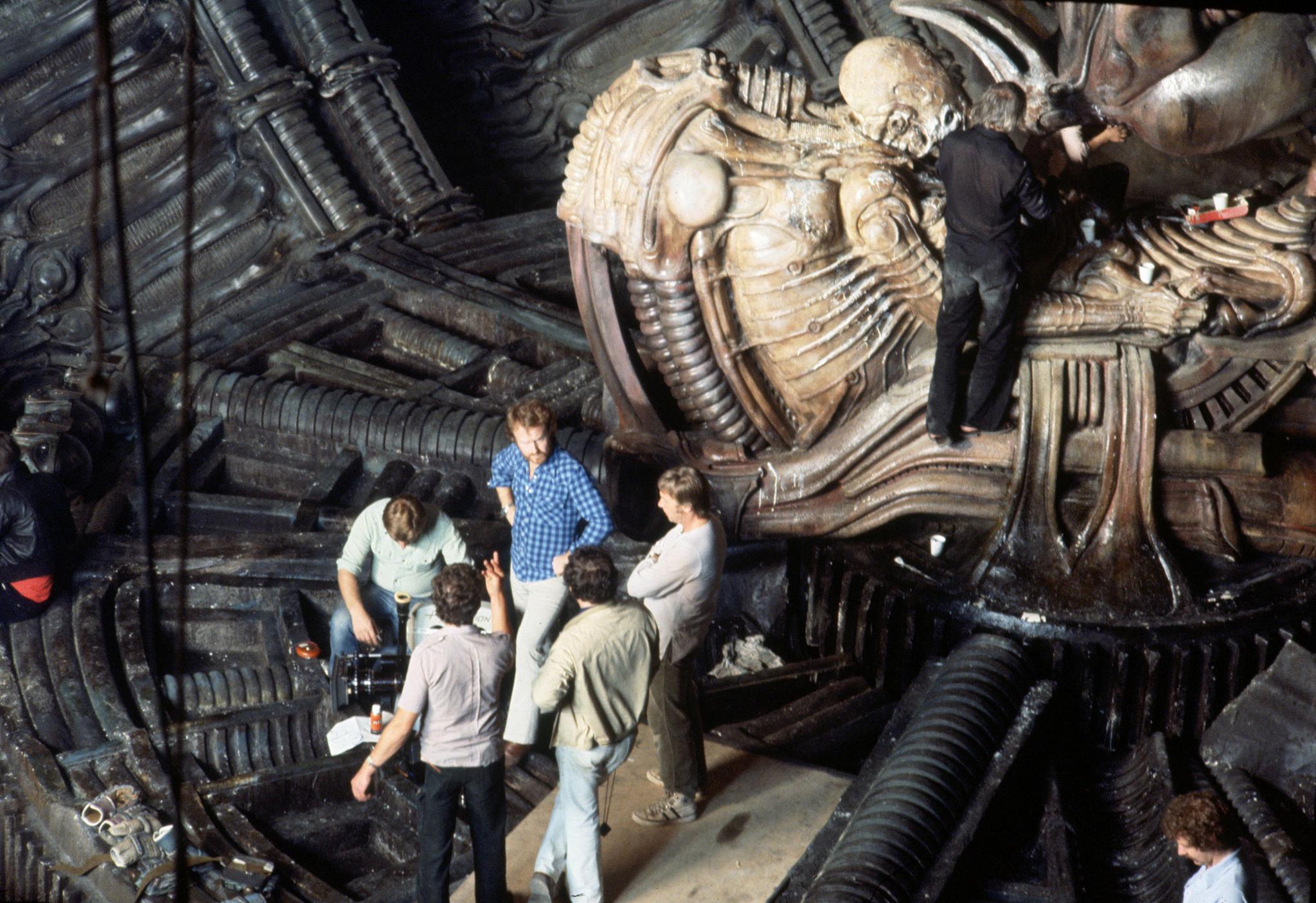

Here are several photos taken behind-the-scenes during production of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner. Photographed by Stephen Vaughan © Warner Bros. Blade Runner Souvenir Magazine Official Collector’s Edition was published in 1982 by Ira Friedman, Inc. of New York. The Blade Runner film, “Blade Runner” trademark are Copyright © 1982, 1991 by the Blade Runner Partnership and/or The Ladd Company. Additional images and content are Copyright © Warner Bros. All of these are used on this site purely for educational and research purposes only under “Fair Use” law.

If you find Cinephilia & Beyond useful and inspiring, please consider making a small donation. Your generosity preserves film knowledge for future generations. To donate, please visit our donation page, or donate directly below: