That Obscure Object of Desire

The Peter Webber Interview

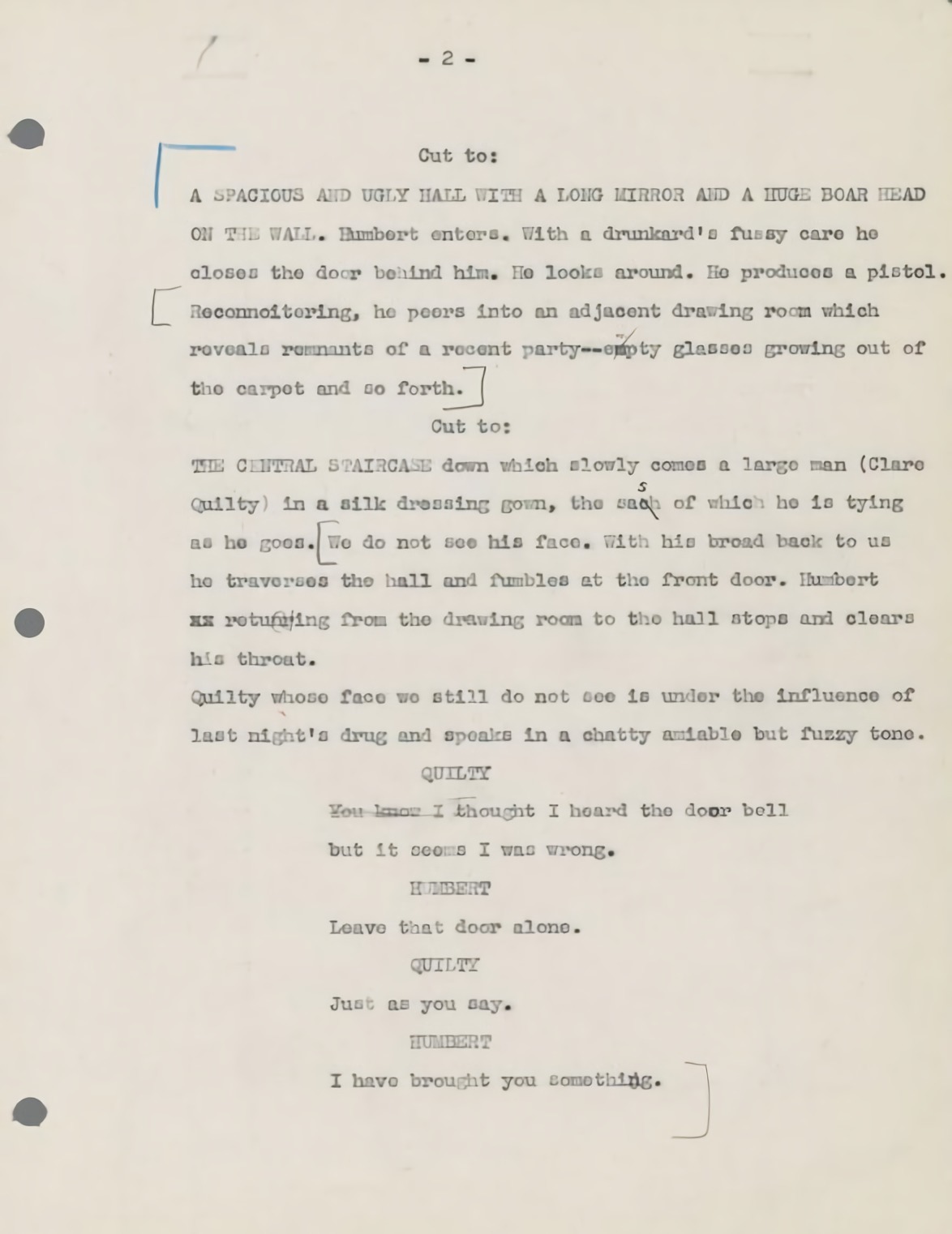

by Sven Mikulec

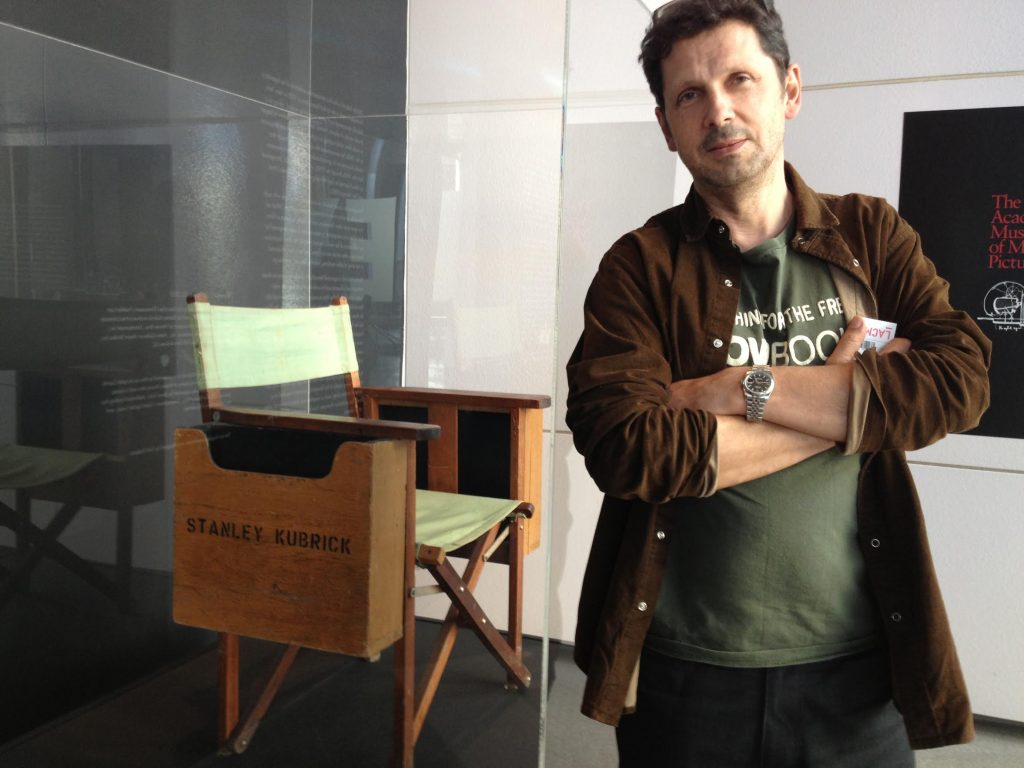

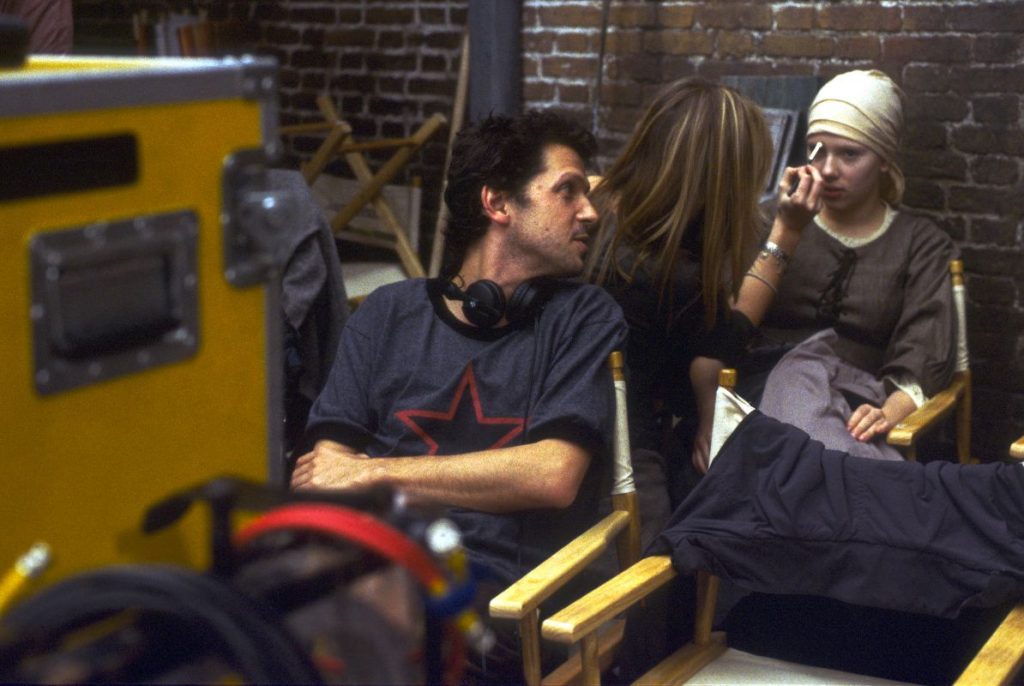

Peter Webber, who delighted us back in 2003 with his charming debut Girl with a Pearl Earring, proved to be a capable director, a very nice guy but, above all, a truly devoted lover of the art he chose to be his life calling. When we decided to do a series of interviews with filmmakers who’ve shown passion for collecting film memorabilia and take deserved pride in owning pieces of cinematic history and drawing inspiration and strength from them, Peter seemed a perfect choice for the series’ opening interview. The British filmmaker has recently acquired the great Stanley Kubrick’s beloved Mercedes, not only a beautiful, elegant and powerful car, but given Kubrick’s history and often discussed love for these vehicles, also an item of truly mythological appeal and significance. During a cordial chat with Peter on a lazy Tuesday morning, we’ve talked about his career, passion for the arts and, of course, the quite unique feeling of cruising around town in what many would call the Excalibur of film memorabilia.

So, you bought Stanley Kubrick’s Mercedes. As far as film memorabilia is concerned, that’s more or less the Holy Grail. How did you get your hands on it? Who’s been its owner since Kubrick died?

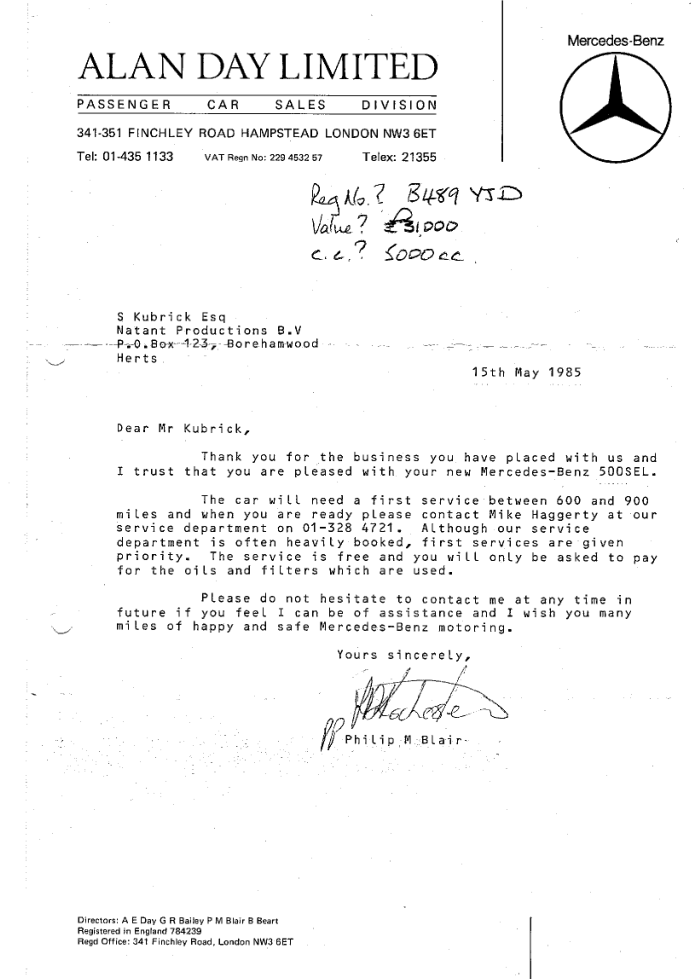

WEBBER: It’s actually a kind of a Twitter story. You know how you can have various searches saved on Twitter? Well, one of the searches I saved was Kubrick. Every now and again when I’m bored I go up to see what Kubrick tweets have come up. I’m a big fan and I did this one day, and a tweet came up saying Stanley Kubrick’s car was for sale. I looked into it and, sure enough, it was someone who claimed to be selling Kubrick’s last car, this Mercedes, and I thought this must have been over since the ad had been up for a while. Especially when I looked at the price, which, for a second hand car in London, wasn’t expensive. So I got in touch with the guy because it looked as if it was still available, and he said someone else was interested in it. But because I lived in London, I was able to get up there straight away. It was as simple as that—the Internet led me to the car. I met the guy, who used to be an agent himself, and was a friend of the person who had bought it from Kubrick, he showed me all this documentation, and I scanned some of this stuff—especially the letter from the dealership to Stanley Kubrick. I made an offer then and there, which he accepted, I gave him a deposit, I had to go off to France that weekend, I came back from France, paid the rest and drove the car away. There we go. Very simple story.

It’s fascinating to see all the things you can get done over the Internet.

WEBBER: Yeah, I know, that’s one of the reasons I spend far too much time on it. (laughs)

There’s one hell of an anecdote. When Kubrick was filming The Shining, he kept eating Big Macs all the time. When he finished one of these sandwiches, he tried to throw the rubbish through the sunshine roof, but the wind tossed it back, all over him. “Fuck,” he said. “This car isn’t much good.” What about yours? Are you happy with it? What’s it like to cruise in that baby around town?

WEBBER: It’s a Mercedes 500 SEL from about 1984. It’s in a good state, it’s parked just down the road from me. Owning a car in London is not a wonderful thing, it has to be said, and it’s quite a big boat of a car. I don’t actually drive it that often because I live right in the heart of London so I mostly either use the public transport or walk. But once a week maybe I take it out for a few long drives. But when I do take it out, I just like to sit there with one of soundtracks of Stanley Kubrick’s movies. Like Barry Lyndon or… actually, A Clockwork Orange is one of my favourites, so I just have that blasting away. I don’t think Kubrick actually drove it a lot, he had a driver, so I sort of imagine Stanley being in the back, the ghost of Stanley anyway. I know it’s sentimental and it’s silly, but I find it quite exciting, it brings me closer to him, you know. It’s very, very cool and it’s great to have this strange bit of memorabilia.

We know how Kubrick held his cars dear to him. So in a way, a part of him remains with you?

WEBBER: Yes, completely. It’s interesting, he seems to have been very fond of his Mercedes, despite the fact that he seems to be kind of anti-technology in some of his films, like Strangelove or 2001. He’s very quizzical, let’s say, about technology or at least the interface of technology with humanity. In his own personal life he really loved these machines. I haven’t come around to doing it yet, but what I was planning on doing is making a short film. I know a lot of people who worked with Kubrick and I thought it would be really nice to make a short film in which I drive them around with a set of GoPros inside the car, doing little interviews. I must get on to do that, as a personal project of mine.

This sounds like a marvelous idea.

WEBBER: Well, if I do that, I’ll make sure you guys get the preview.

Kubrick is one of the great giants of cinema. But more than that, it doesn’t only have to do with his films, he’s a legend. There’s a mythology around him. That’s one of the things I find really fascinating. We know he was good at all aspects of his job. He was as good as a soundman, he was as good as a cameraman, he paid legendary attention to detail, we know his obsessiveness about every single… For example, here’s a Kubrick story that shows the kind of precision and attention to detail he became known for. I was reading about how he wanted his assistant to order a new blind for a window in his study. And he went and measured it, and because of Stanley, he thought, I won’t just measure it once, I’m going to measure it twice. He wrote a note to Stanley: I measured up the window, these are the dimensions, this is the blind that I ordered, I didn’t measure it only once but twice, and then I double-checked it. And Stanley wrote him back saying, yes, but did you check the tape measure? (laughs) There are dozens of stories like this. I’ve worked with some of Kubrick’s crew, for example the guy who was the camera operater on The Girl With a Pearl Earring and he also shot the first half of Hannibal Rising, Mike Proudfoot. He worked with Kubrick on Barry Lyndon, he looked after the lens. Whenever I work with the people who worked with Kubrick I always quiz them. There’s this mythology around him, and I’ve been obsessed with it ever since I first became interested in cinema. So just to be able to sit in that car and to cruise around town at night, as lights splash through the window and the music of one of his soundtracks is playing, it’s a marvelous feeling to feel his presence in the back of the car. I call the car Stanley, of course. (laughs) I anthropomorphized the car. I know it’s slightly foolish, but I find it wonderful. And to have a letter in my possession addressed “Dear Mr. Kubrick,” as an enormous movie fan, that’s very inspirational. I know that I’m never going to be a giant of cinema the way Stanley Kubrick was, but I hope some sympathetic magic would rub off. That one day in the future I’d make a film that comes close to one of his. I still haven’t done that but I keep my fingers crossed it might happen one day.

Besides the car and the letter, are you a fan of collecting film memorabilia in general?

WEBBER: I don’t have an enormous collection, I’m afraid to say. I always keep bits and pieces from the films I worked on, and now and again I come across things. It’s not like my office is full of things that once belonged to John Ford, or something like that. I’m not really a collector in that way. Apart from books maybe, you know. I do really like books, I have many, many books on Kubrick and other filmmakers. I think it’s the particular kind of magic that surrounds Kubrick that made me collect these things. I recently went to see the travelling exhibition, I don’t know whether you had the chance to see it yet. I think it was in Amsterdam, and in Berlin for a while. It has various artifacts from his films and numerous memorabilia from over the years. There’s something that’s just more exciting about Kubrick’s films than that of other directors, especially other recent directors. It might be different if you went back and got things that belonged to E. W. Griffith or someone, that might be interesting. Maybe the only other directors that I’d be interested in the same way is the stuff that belonged to Jean-Luc Godard when he was young, from that first phase between 1961 and 1966. But he’s still alive, it’s not the same, you know. There’s something about when people pass on that they turn to legends, while they’re still alive they’re just human beings.

If you could get your hands on any film memorabilia in the world—any, but only one—what object would you choose and why?

WEBBER: I’d probably get Alain Delon’s hat and coat from Melville’s Le Samouraï.

I know it’s a cliche, but it became a cliche because it’s such an important question: what made you fell in love with the world of film? Why did you become a filmmaker? When did you know that this was what you were supposed to do?

WEBBER: There is a moment actually, there is one moment. I was interested in movies when I was really young, and my dad took me to see 2001, but I didn’t understand it, I mean I was a kid. I remember walking home and trying to get my father to explain the film to me. Which I don’t think he did very successfully, but it’s difficult to try explain this to a young boy. I remember the moment when I really became aware of the role of the director, let’s say, and decided that was what I wanted to be. I was a fifteen-year-old kid, in West London in an old cinema called The Electric. Somehow, by accident, I went to see this Godard’s film, Pierrot le Fou. The thing about Pierrot, I think it was the first film I saw really that was an art film, that was an auteur film, not just meant to be entertainment, and it made me really aware of the camera. You have actors turning around and talking into the camera in the middle of takes. It’s a thriller, but it’s a meta-thriller as well, something that investigates the very idea of being a thriller. I found it funny, clever, smart and like nothing I had ever seen, and I fell in love with Anna Karina as well. That just filled me with a kind of a promise of… it revealed the cinema as something magical and full of promise. From then onwards I was completely addicted and spent most of my teenage years in the darkness of that cinema watching old movies. This was before VHS, before DVD… Maybe VHS had just come along, but it really wasn’t that available. It was sitting in those stalls in the Electric cinema that gave me my first education in cinema. So Pierrot le Fou was the first one that really piqued my interest.

So since you were fifteen you really had no doubt about what you wanted to do?

WEBBER: I had no doubt about what I wanted to do, but I had a lot of doubt about whether I could do it. I mean, it’s not like at fifteen years of age I decided what I was going to do and that was it, you know. I was still in school, I went to college, I didn’t go to film school until I was in my mid-twenties. It took a long time really to get to the point of deciding that it was something I couldn’t live without. Later I worked as an editor, I worked on TV, a made documentaries… it took a long time until I finally got to do movies. But it all started when I was fifteen. The thing is, way back then, there weren’t many film schools, we didn’t have the access to the equipment like we do today. If you got a smart phone, you got a camera on it. If you got a laptop, you can edit the film and instantly upload it to Vimeo or YouTube. That was completely impossible. The equipment was really expensive and hard to come by. It was a very different world. There’s a lot more accessibility now, and in a sense many more people want to do it. It was something I wanted to do from the early years, but it took many years for me to realize there were possibilities for me to actually be able to do it.

You’re an Art History major. The obvious connection is the passion for the visual. To what degree did this knowledge from your studies help you become a better filmmaker?

WEBBER: Yeah, that’s right. The first time I went to the university was to do Art History. The second time, as a post-graduate, I did a film course. It really helped a lot, I didn’t realize it at the time, but it helped on a number of levels. I mean, you look at a painting, especially figurative painting and old paintings, you learn about composition, you learn about lighting, visual storytelling, iconography… There’s so many things you can learn about and if you absorb those lessons, then it makes you a better filmmaker.

On one occasion, Kubrick said: “Perhaps it sounds ridiculous, but the best thing that young filmmakers should do is to get hold of a camera and some film and make a movie of any kinds at all.” What would be your advice for young filmmakers on the start of their journey?

WEBBER: I think that’s true. I think that going out and actually making something… it’s one of those things where you really learn by doing it. But that’s not the only important thing. The other important thing, I think, is to develop points of view and to have something to say. For example, you need to understand film history, you need to understand art, you need to understand literature. You really need to work on yourself and turn yourself into an artist. You need to understand as many different media as possible. You need to be well-read. I think there’s a lot of fanboys cinema at the moment, because we live in the age of Marvel and superheroes. I think we lack more fully rounded filmmakers.

I went to see Werner Herzog talk last night. There’s not a lot of people like Herzog today, he’s a man of enormous cinematic experience, he really knows art, he knows literature, he knows music. And I think that the more that you can grow your aesthetic sensibility, and the more you understand and appreciate what’s out there in the world, the better films you make. So, I’d say there are three things. The first thing is, yes, go out and do it. The second thing is know your film history. And finally, you have to build some kind of cultural hinterland. If you work on all these things, then you can turn yourself into an actual film director.

Your film debut, Girl with a Pearl Earring, was widely praised and was awarded with three Oscar nominations. It sounds as a debut a filmmaker can only dream of. Eleven yours later, how do you feel about the film?

WEBBER: It’s difficult for me to talk about the film because I haven’t seen it in eleven years. When I make something, it’s not mine anymore, it belongs to the world. I certainly don’t know many filmmakers who sit around at home, watching their own stuff. (laughs) Because you’re more worried about the next one. It changed my life. I worked many years as an editor and documentary filmmaker, also making drama for British TV. It was a wonderful experience and a great honor that it was received so well. I have nothing but good feelings about it. This is a tricky business, you know, and certainly getting trickier. The world is changing, the world of cinema is changing. I think ten years down the line, being older and wiser, I could enjoy watching it. What can I say, I was very young and naïve at that time and I didn’t realize how precious that moment of big success was. I’m grateful to the producers for picking me to make the film and happy that people still regard the film warmly in their memory.

You have to remember that as a filmmaker not only are you on set every single day, grinding the work out, but you also sit in the editing room and see those images again and again and again and again. Then you finally get your cut, and then you’re grading it, doing the sound work, doing the sound dub. So by the time you finish it, and this is true for most filmmakers I know, if not all of them, you’re kind of sick of it, it’s over. (laughs) You get your pleasure from the process of making it. Also, most filmmakers I know see their mistakes as they’re watching it. That’s what drives you to move on because most of the people I know are fully aware of the flaws in their work and they hope to make one decent film before they die.

When you were to make Girl with a Pearl Earring, you specifically asked to work with Portuguese cinematographer Eduardo Serra. How come?

WEBBER: It was just something about the quality of light, something quite transcendental about his work, and I was really aware of his work, a big fan. It seemed to me that he had the appropriate visual sensibility, which turned out to be true, he did an amazing job. He’s a wonderful, wonderful man to work with. I think it was Robert Altman who said that when you cast or you crew a film, that’s really 90 percent of the work. If you do it right, you’ve done most of the work. Because filmmaking is a collaboration with your actors and crew. We chose excellently who we worked with and I think that was the reason we succeeded in making a film that people embraced.

In Emperor you tackled with immediate post-WW2 history. You mentioned something about being a history buff?

WEBBER: When I was younger I used to read a lot of fiction, but as I grew older I started reading more factual, more historical stuff. And I don’t think I’m uncommon in this way. Once you get to be a middle-aged man, you tend to become more interested in these things. I find that history is very illuminating. We live in a very chaotic world, a dangerous, violent world where awful things happen and it seems to be getting worse. And one way of understanding all of this is by looking at history. I think there’s something quite amazing that films can do, they are like a time machine, you know. What vision do we have of life in the 1780s or something? Your vision is to do with paintings, but it’s actually to do with films like Barry Lyndon also. That film is the closest we’ll get to sitting in a time machine and going back there. To be involved in that, to get absorbed in the minutiae of the details, is a very compelling thing. It also happens that the majority of the projects I’m offered tend to be historical, because people pigeon-hole you very quickly. It fits with my interests, I’m very absorbed in trying to take lessons from the past and see what they can teach us today.

One questions that you always have to ask yourself is—why this story and why now? I currently have a couple of things that I’m developing with historical characters. You need to find a story that speaks to the present day in some way. But there’s too many to make a choice. The world of history is enormous, and I don’t think we’ll be running out of characters any time soon. The only thing is whether we’ll run out of the audience’s attention. I mean, I was shocked to realize when I was doing some screenings of the Emperor that there’s an awful lot of young people, especially in America, I have to say, where the state of education seems to be lamentable, who really have no idea about the world. For example, I read this newspaper article where a war veteran was talking to high school students on the anniversary of Pearl Harbor. So he went to the school and said, I’d like to talk to you about Pearl Harbor, and one of the kids raised his hand and said, Pearl Harbor? Who is she? It’s something that’s really, really worrying. Maybe making films about history is the best way to bring it to people’s attention. Because there’s so much that bombards us, the present surrounds us, we’re on our devices, on our computers, look at all the information that’s coming to us. There’s really no time to stand away and contemplate about the past. I think it means the world loses connection little by little. For me, that’s a great reason to tell these stories.

You mean, films should have an educational purpose?

WEBBER: Yes, but educational makes it sound very dry and boring, doesn’t it? (laughs)

But it seems to be necessary, doesn’t it? I saw on Twitter a while ago that people were shocked Titanic was based on an actual event.

WEBBER: Well, exactly! You look at that nonsense and you realize, oh my God, there’s a lot of really stupid people out there. I think we’re at a time when we need as much education as possible. I’ve just finished this film called Ten Billion which points out some of the problems that will be heading our way, and actually are heading our way right now, in terms of global warming, food security and population growth, and I just wonder how well equipped we are to deal with these. We seem to have entered an age of stupidity.

When can we expect to see it?

WEBBER: Well, listen, I’m doing some post-production fiddles with it. As you know, we’ve put out a teaser trailer and I’ll have more information on that over the next month or two. You’ll be the first to know. It will roll out during this year.

Do you go to the cinema? Do you have time to see contemporary films? If so, which ones did you enjoy the most?

WEBBER: I do go to the cinema. Not as much as I used to, but then again, I used to practically live at the cinema when I was a kid. And nowadays I’m lucky enough to have in my possession a very good projector so I can create my very own cinema-like conditions. It’s like a small multiplex, I have really good screening facility here. I do go, but I prefer old films than new. That’s really why I watch a lot more stuff at home than at the cinema.

My favourite director is one of the least known. He’s called Panos Cosmatos and he made a film called Beyond The Black Rainbow. Which to me is the most amazing, interesting, very low budget, styled on 80s horror films, but I think it’s a marvelous thing. I think he’s a basically an ignored genius, Panos is. I’ve also enjoyed The Tribe by Myroslav Shlaboshpytskiy, Court by Chaitany Tamhane and A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night by Ana Lily Amirpour.

With grateful thanks to Peter Webber for these stunning photos.

Get Cinephilia & Beyond in your inbox by signing in

[newsletter]