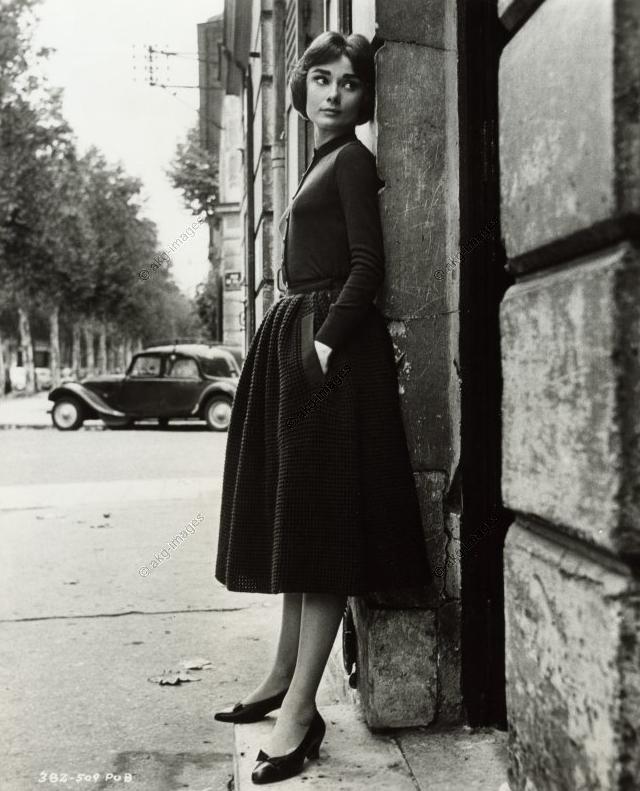

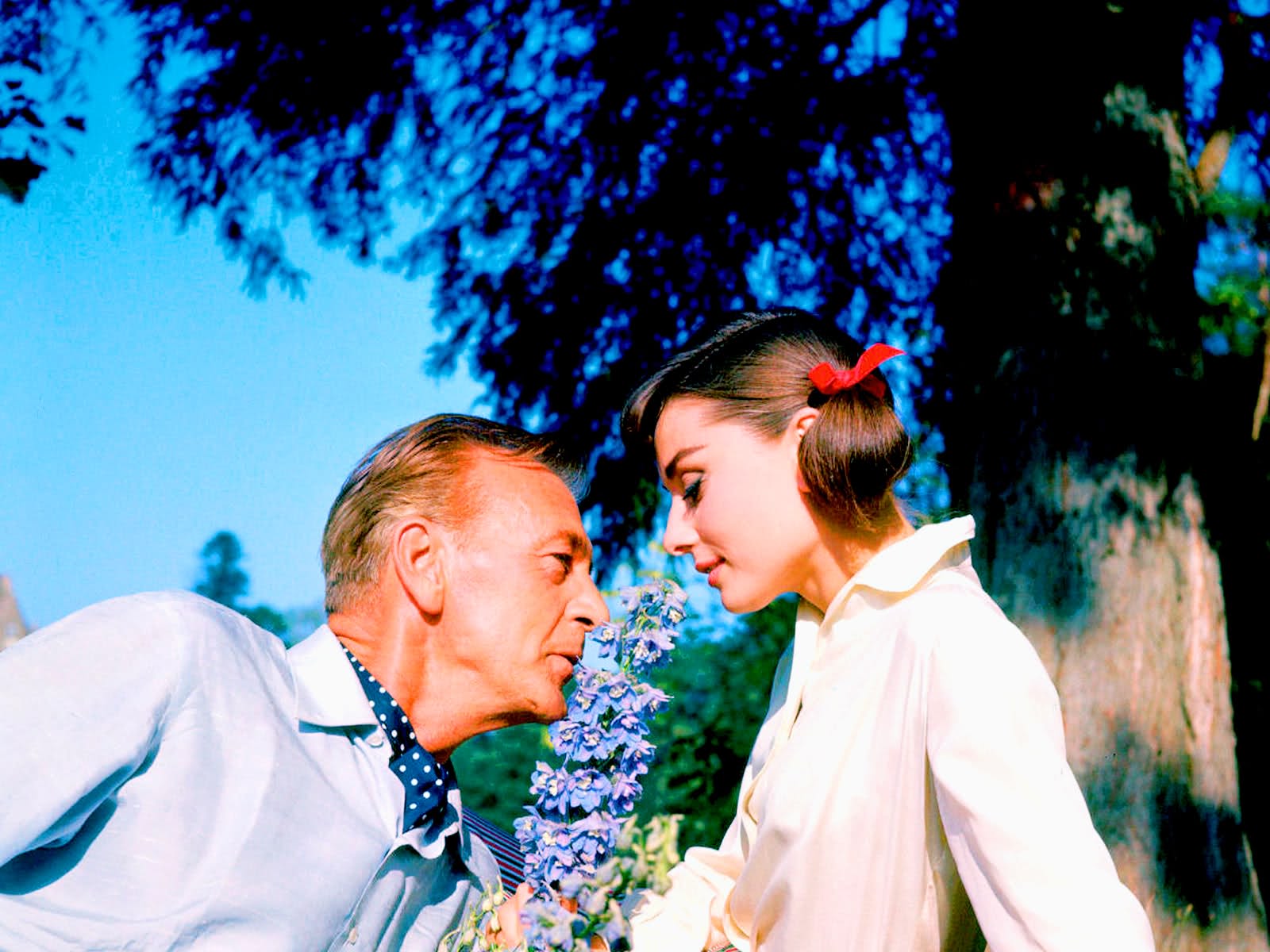

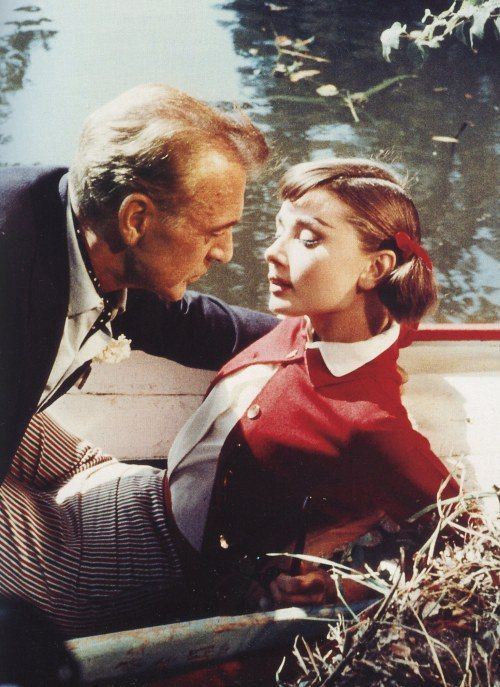

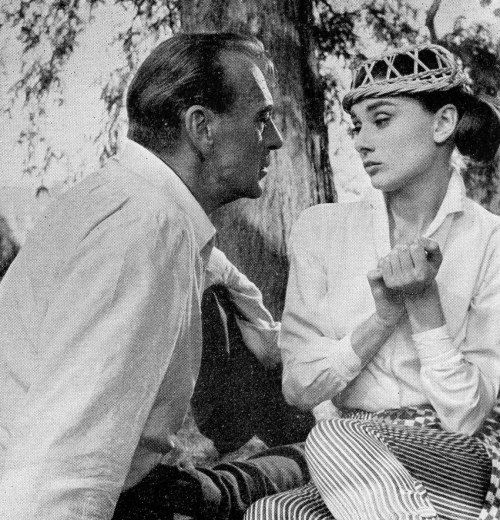

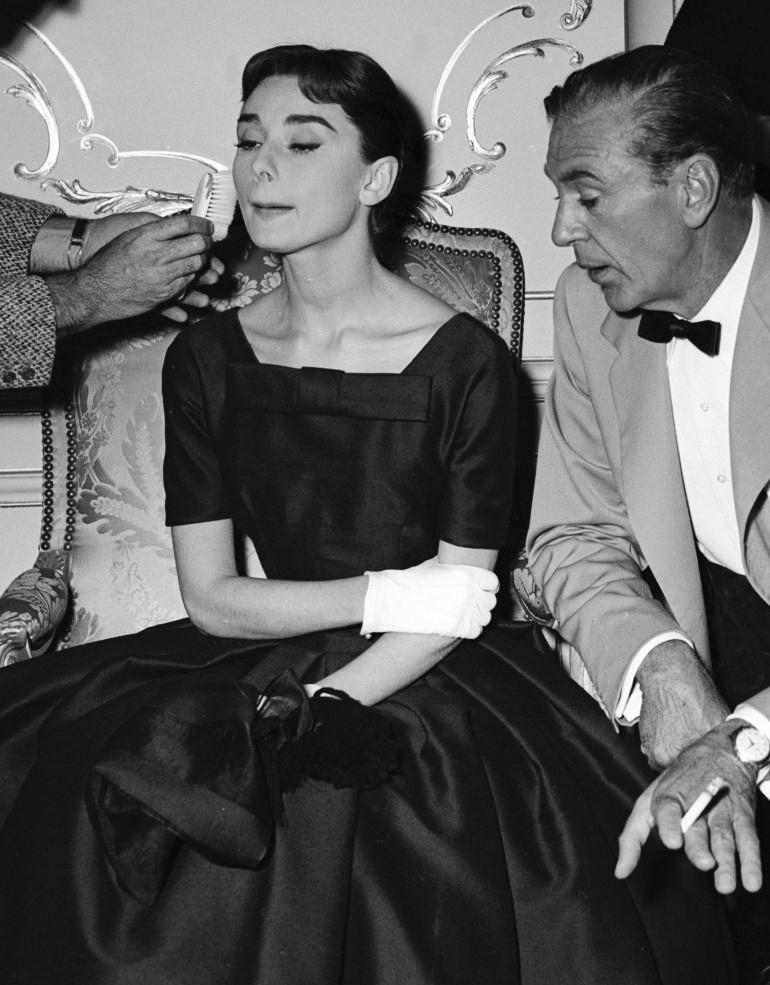

The first of twelve screenplays written together by the great Billy Wilder and his dearest collaborator, screenwriter I. A. L. Diamond, the 1957 romantic comedy Love in the Afternoon is a charming love story carried on the shoulders of the wonderful Audrey Hepburn, Gary Cooper and Maurice Chevalier. Set in the City of Light, the eternal metaphor for unrestrained love and fulfilled desires, Love in the Afternoon is a sophisticated romance echoing the work of Ernst Lubitsch. Wilder is often referred to as a true student of Lubitsch, and in this film it’s easy to see who his great source of inspiration was. What’s especially interesting about this film is the way it skillfully pulled off portraying the love affair in question. The story of a middle-aged playboy winning the heart of a young, blossoming girl is by definition a possible source of general moralistic disgust. The age difference between Gary Cooper and Audrey Hepburn was no less than 28 years, and you have to remember that the film had its premiere back in 1957, when it was scandalous even to show a semi-clothed woman on screen. In order to avoid any conservative outrage from the audience regarding the staggering age difference between Cooper and Hepburn, Wilder decided to delicately handle the matter, carefully choosing how to visually present their romantic affair on screen, cautiously inserting scenes in which, for example, Cooper kisses Hepburn’s bare hand, scenes which only hint at what might be going on behind closed doors and shut blinds.

A solid proof of to which lengths the filmmakers went to sooth the situation is the fact the American version of the film ends with a narration explaining the two protagonists are now married and living in New York, while Cooper’s line “I can’t even get to first base with her” was reportedly dubbed into the film so no one would call Hepburn’s character’s decency into question. The film ultimately caused no controversy, but some critics found the Cooper-Hepburn relationship convincing and lacking chemistry. We’re definitely not among those people, able to appreciate the wonderful interaction between the two characters, complementing each other with experienced charm and childish seductiveness. Love in the Afternoon belongs to the impressive line of exquisite American romantic comedies one should not miss.

Dear every screenwriter/filmmaker, read Billy Wilder & I.A.L. Diamond’s screenplay for Love in the Afternoon [PDF]. (NOTE: For educational and research purposes only). The DVD of the film is available at Amazon and other online retailers. Absolutely our highest recommendation.

Loading...

Loading...

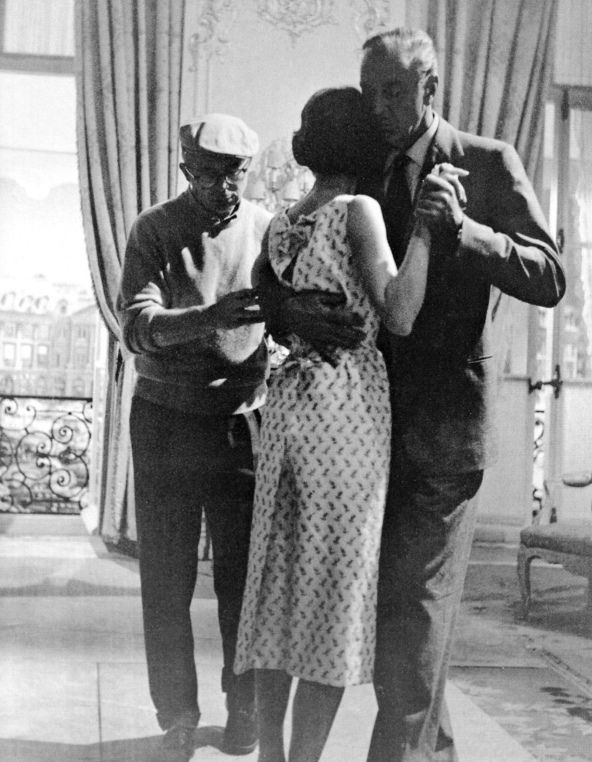

These are the two main signature shots of the great Hollywood filmmaker Ernst Lubitsch—especially during his Hollywood heyday, the 30s—and one can also find variations of the second kind, the outside-the-door interiors, in the more romantic movies of Billy Wilder, Lubitsch’s major disciple, whose own Hollywood heyday was the 50s. In Lubitsch’s Ninotchka (1939), which Wilder and his frequent writing partner Charles Brackett helped to script, we’re made to understand how much three Russians in Paris (Sig Ruman, Felix Bressart, Alexander Granach) on a government mission are enjoying themselves in their hotel suite when they order up cigarettes, meaning three cigarette girls. And in Wilder’s Love in the Afternoon (1957)—the most obvious and explicit and also, arguably, the clunkiest of his tributes to Lubitsch, partially inspired by Lubitsch’s 1938 Bluebeard’s Eighth Wife (which Wilder and Brackett also helped to script, and which also starred Gary Cooper, again playing a womanizing American millionaire in France)—the camera periodically returns to its favorite spot, outside the millionaire’s suite at the Ritz, whenever the Gypsy musicians he hires arrive to help him pull off his various seductions with their soulful rendition of ‘Fascination.’ —Jonathan Rosenbaum, Sweet & Sour: Lubitsch and Wilder in Old Hollywood

In Conversations with Wilder, Hollywood’s legendary and famously elusive director Billy Wilder agrees for the first time to talk extensively about his life and work.

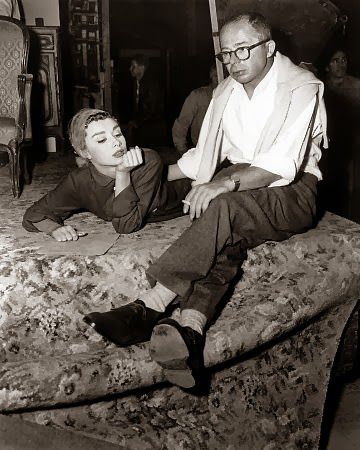

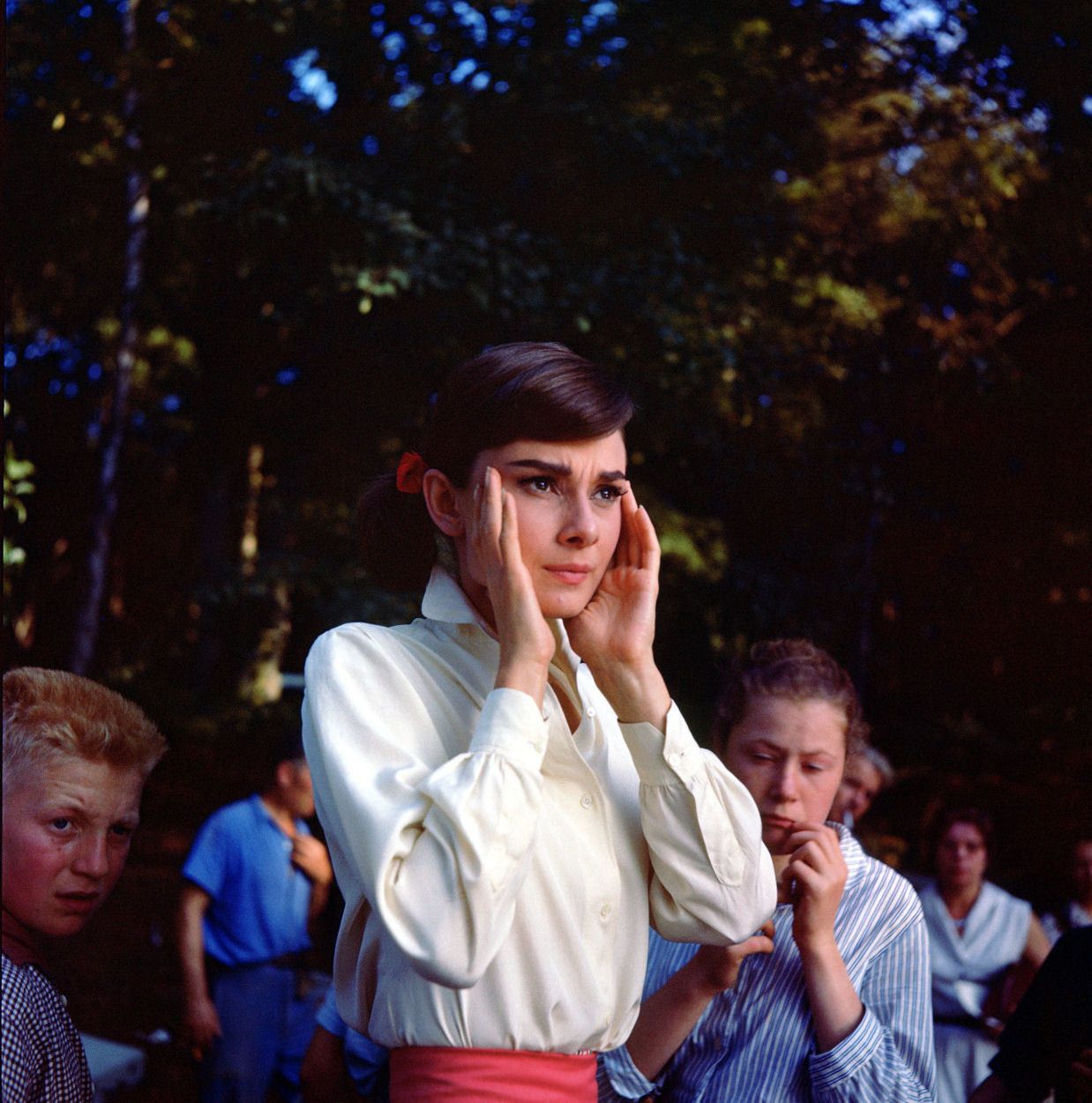

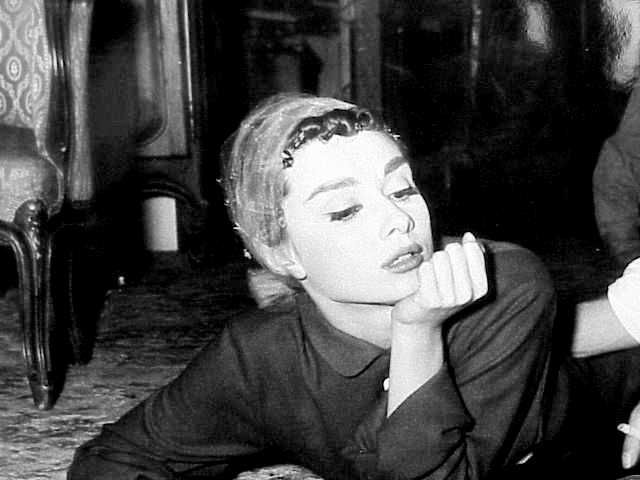

CROWE: I once heard this advice: When directing a romance, or a romantic comedy, a director must fall in love with his leading lady through the lens. “If you don’t, no one else will.” How did it feel to direct Audrey Hepburn [who starred for Wilder in Sabrina and 1957’s Love in the Afternoon]? Did you fall in love with her, through the lens?

WILDER: Of course. There was so much inside her, a feeling that communicated. But was she “sexy”? Off-camera, she was just an actress. She was very thin, a good person. Sometimes standing on the set she disappeared. But there was something very likable about her. You trusted her, this tiny person. When she stood before the cameras, she became Miss Audrey Hepburn. And she could put it on a little bit, the sexiness, and the effect was really something. For instance, in Sabrina, when she came back from Paris with the dress. There was gold in that picture… —Conversations with Billy

PORTRAIT OF A ‘60% PERFECT’ MAN: BILLY WILDER

Billy Wilder’s acerbic wit and indomitable talent shine through in this documentary by Annie Tresgot. Michel Ciment, the French critic, interviews Wilder about his life and movie-making, and Tresgot also brings in discussions with Walter Matthau and Jack Lemmon. Few directors have been as consistently successful as Wilder who made movies as varied as Ninotchka in 1939, Witness for the Prosecution in 1957, and Casino Royale in 1963. At the time of this interview the director was 74 years old, and emphasizes the fact that his life is not just about movies. Born in Austria, he came to the U.S. to escape Nazi persecution and eventually, to find his own expression in the growing film industry. —Eleanor Mannikka, Rovi

“You will not find in my pictures any phony camera moves or fancy setups to prove that I am a moving-picture director. My characters don’t rush around for the sake of being busy. I like to believe that movement can be achieved eloquently, elegantly, economically and logically without shooting from a hole in the ground, without hanging the camera from the chandelier and without the camera dolly dancing a polka.” —Billy Wilder (June 1963)

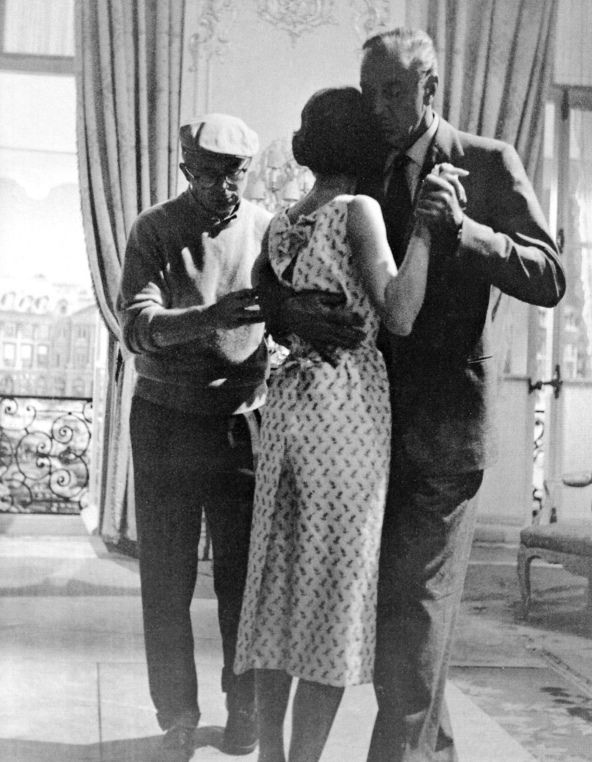

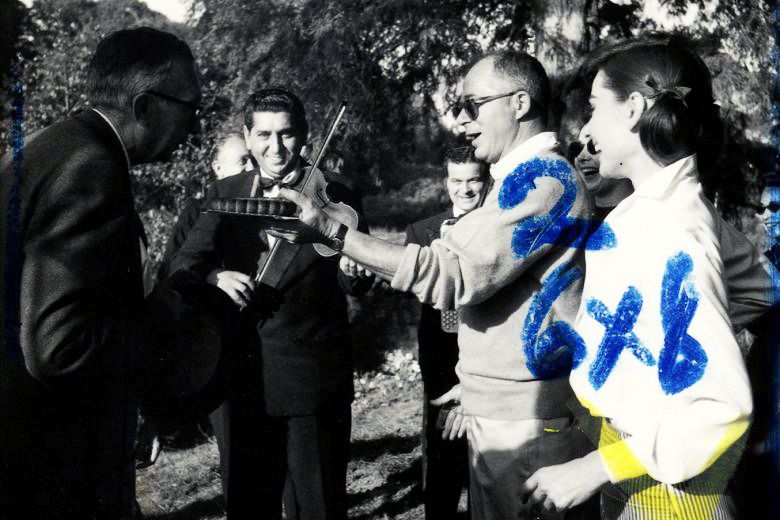

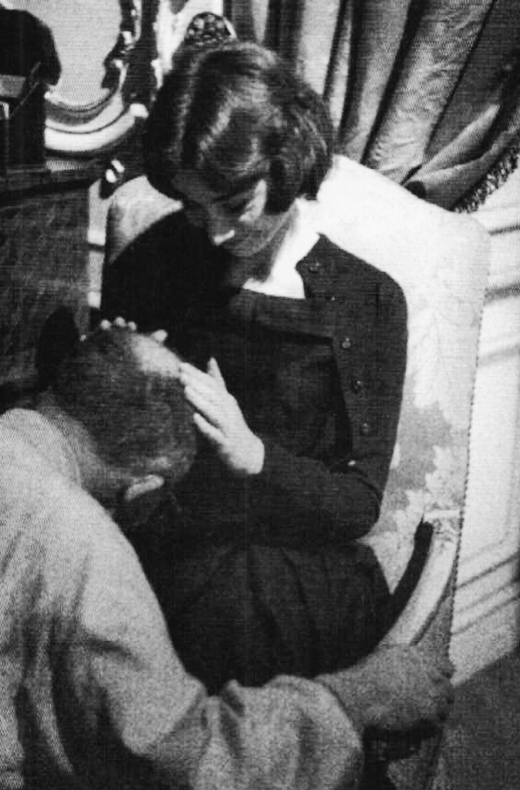

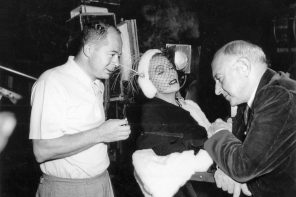

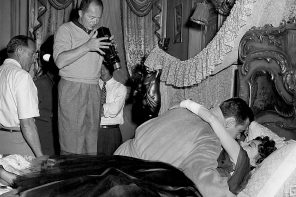

Here are several photos taken behind-the-scenes during production of Billy Wilder’s Love in the Afternoon. Still photographers: Al St. Hilaire & Richard Walling.

Get Cinephilia & Beyond in your inbox by signing in