By Sven Mikulec

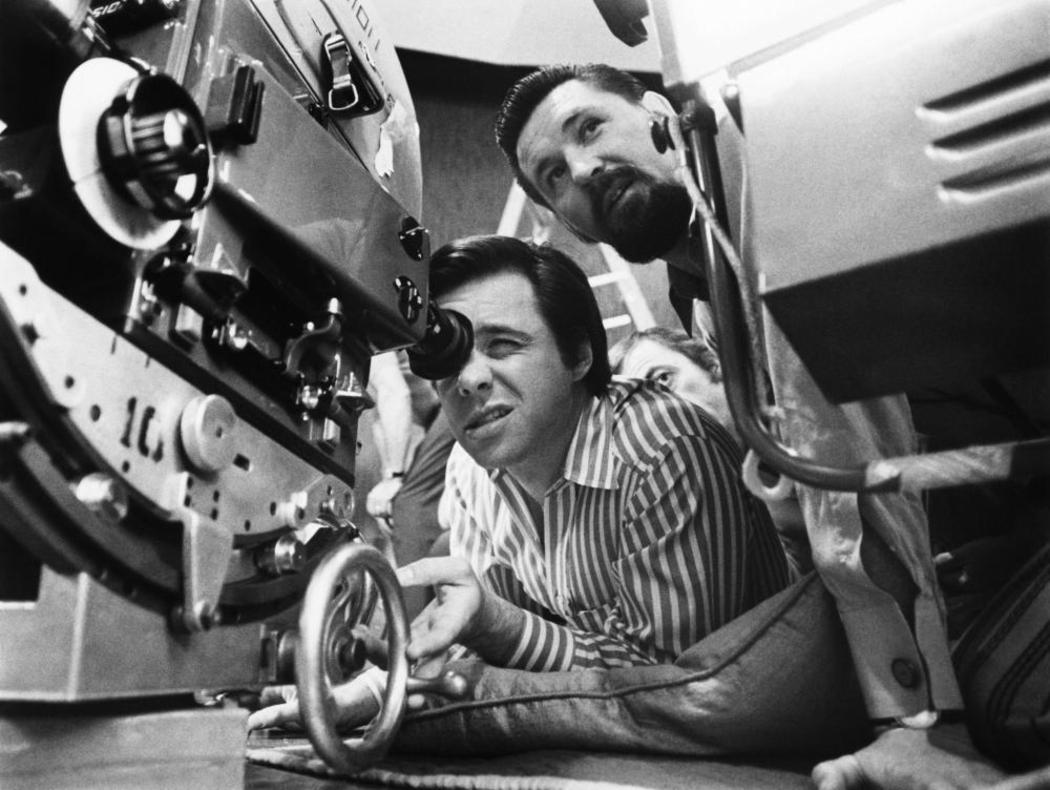

Peter Bogdanovich’s disarmingly charming screwball comedy What’s Up, Doc? is not just a highly entertaining comedy with very nice performances and tons of goofy humor—it’s also a nice, retro, comparison-worthy homage to the movies that ruled the box-office back in the thirties and forties. Bogdanovich envisioned a sort of a remake of Howard Hawks’ Bringing Up Baby, and even if this information had remained undisclosed, it would still be rather easy to recognize the source of the filmmaker’s inspiration. Incredibly fast-paced, stuffed with uncountable sequences of overlapping dialogue and manic interactions, presenting a series of finely shaped characters and delivered gracefully thanks to the talents of its impressive cast, What’s Up, Doc? absolutely and instantly won over the audience, becoming the third most popular film of the year 1972 in the United States, right after The Godfather and The Poseidon Adventure.

The film ended up being the second-biggest hit of the year, after The Godfather, which actually I turned down because I didn’t want to make a Mafia film. There was an early, glitzy screening of What’s Up, Doc? and the audience seemed to be resisting it. They weren’t loose enough for a film like that. It’s like everyone was sitting there asking themselves, “What is this?” There had been some laughs but it wasn’t as warmly received as it would later be by the public. About ten minutes in, John Cassavetes stands up, in the middle of the picture, turns to the audience and shouts, very loudly, “I can’t believe he’s doing this!” The place broke up, and from then on theemy loved it. John and I became friends after that. It’s my favorite review of any film of mine. —Peter Bogdanovich

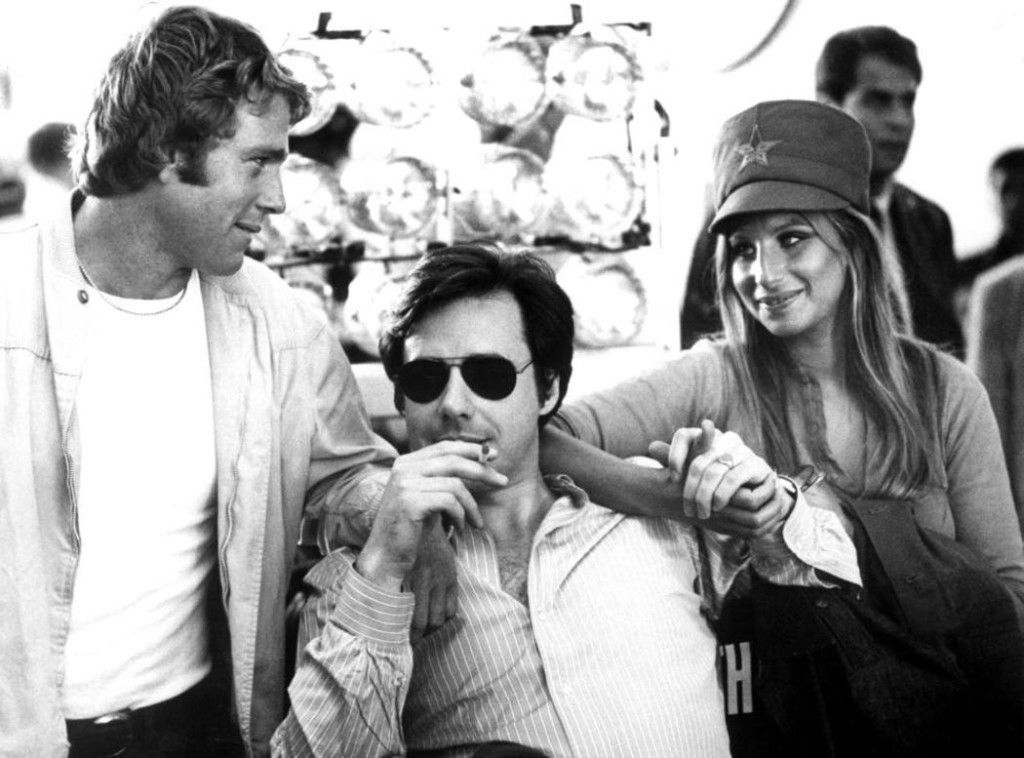

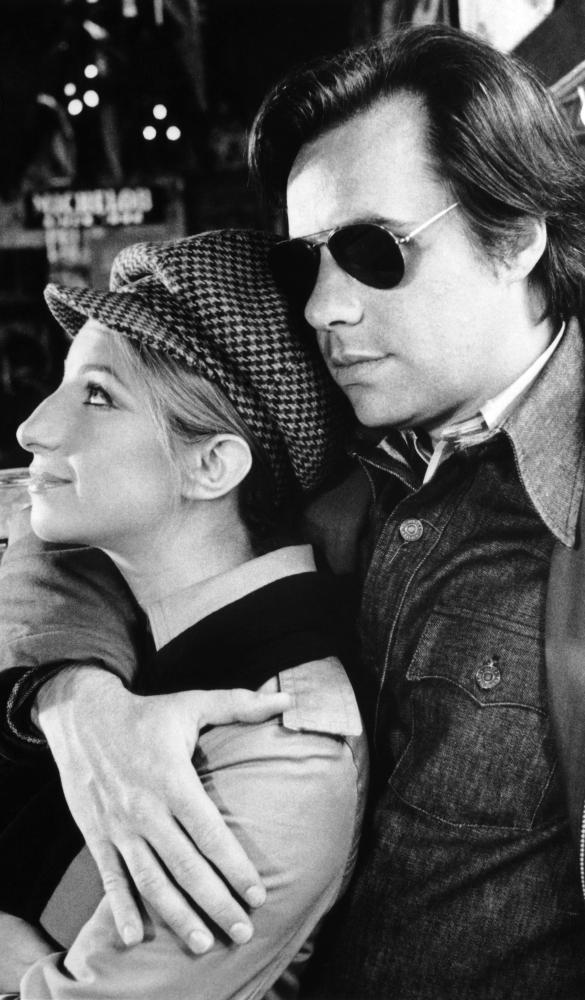

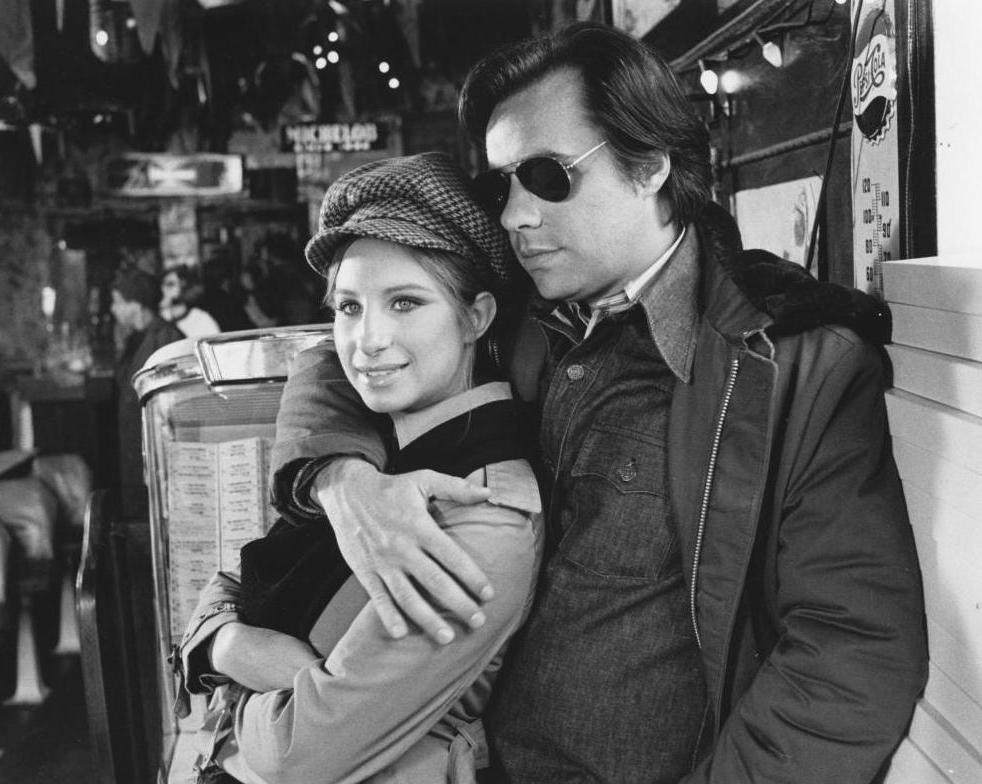

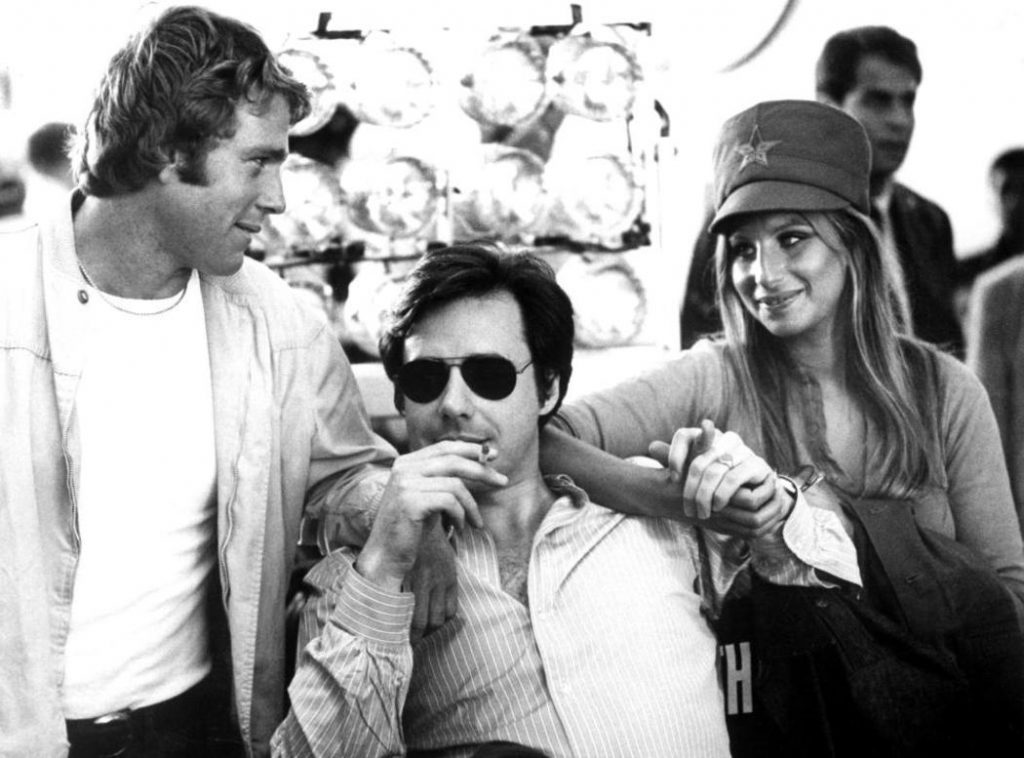

It’s definitely peculiar to note that, despite the fact that Bogdanovich succeeded in getting out the best Barbra Streisand had in store, making the best possible use of her set of comedic skills, his lead actress felt nothing but disappointment by being a part of this film. Although she remained confident Bogdanovich knew what he was trying to do, she considered the film to be a failure, deeming it not funny and sensing a box-office disaster while making it. Years later, after both the critics and the audiences enjoyed it, showering it with awards and recognitions, she hardly changed her mind. But it seems Bogdanovich knew very well what he was doing, remaining faithful to his initial vision of creating a film that would bring to the surface all the memories and sentiment the old Hollywood had to offer. Thanks to the great writing from Buck Henry, Robert Benton and David Newman, there are countless little nods to old pictures that inspired them, from clever dialogue referencing to Love Story to a car chase spoof resembling the one in Bullit. Streisand was marvelous, but couldn’t have done it herself—Ryan O’Neal, her boyfriend at the time, was equally charming, while Madeline Kahn delivered a delightful feature film debut. What’s Up, Doc? brought screwball back to life, and even if it was just for a little while, we remain thankful for this joyful trip down memory lane.

Screenwriter must-read: Buck Henry’s screenplay for What’s Up, Doc? [PDF]. (NOTE: For educational and research purposes only). The DVD/Blu-ray of the film is available at Amazon and other online retailers. Absolutely our highest recommendation.

Loading...

Loading...

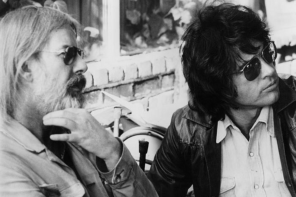

The Writer Speaks: Henry Zuckerman, better known as Buck Henry. The writer of The Graduate, Get Smart, The Day Of The Dolphin, and What’s Up, Doc? talks about his life as a writer.

James Powers moderated this seminar. The transcript also contains segments from seminars Peter Bogdanovich gave at the American Film Institute on May 27, 1975, January 15, 1986, and March 4, 1992, and from an interview conducted in summer 2009. We highly recommend this excellent book by George Stevens Jr. Available from Amazon.

How did you become a director?

I started acting in New York in stock theater and television between the ages of fifteen and nineteen. I worked for the New York Shakespeare Festival and Joe Papp in 1957 as a spear carrier in Othello. I was also studying acting with Stella Adler at the time. At a certain point, some time before I was eighteen, I decided that I’d just as soon not be an actor, that I’d rather direct. It was a big mistake, because actors don’t have to work as hard and get paid more money. The first thing I did as a director was an Off-Broadway production of The Big Knife by Clifford Odets, when I was about nineteen or twenty. Odets was the first person to give me a chance to direct professionally. I did another play Off-Broadway about four years later, Kaufman and Hart’s Once in a Lifetime. During that time I was also writing about movies, because I didn’t have any money and wanted to see them for free. There was a time when I was on every screening list in New York, and I also got all these books from publishers that I couldn’t possibly read. I only had a small room and it was filled with books. I was writing for a strange little magazine called Ivy that appeared about six times a year, and then eventually hit the big time and wrote some pieces for Esquire.

At some point the director Frank Tashlin came to New York. I’d met him in Hollywood when I was doing an Esquire piece about Jerry Lewis. He said, “What are you doing in New York? Don’t you want to direct movies?” I said, “Yes.” He said, “Well, they make them in California.” So a few months later my former wife, Polly Platt, and I were in a car driving west. Soon afterwards I was at a movie screening and Roger Corman was sitting there. He said, “You write for Esquire, don’t you? I’ve read your stuff. Would you ever consider writing screenplays?” I said, “Sure.” He said, “Why don’t you write a screenplay for me? I want something that’s a kind of a combination of Bridge on the River Kwai and Lawrence of Arabia. But cheap.” So Polly and I wrote a script called The Criminals, which was never produced. Right around that same time Roger was doing a motorcycle picture called The Wild Angels and he asked if I would like to work on this picture. I said, “Doing what?” He said, “I don’t know. Just come on down and be with me. We’re having problems with the film. It’s a short shooting schedule, only three weeks, and the script needs a polish. I’ll pay you $125 a week now, and when we’re in production $150.”

I read the script. It was really bad, sort of like a Disney picture. There were things in it like: “The motorcycles roar by. Cut to frog’s POV of motorcycles going by.” There was another scene with a horse and it said, “Cut to horse. Horse looks. Cut to horse’s point of view of fight.” Roger said, “We’re going to start shooting in about a week. We need the script rewritten.” I remember he had a yellow legal pad where he had written about forty pages of notes on the script. He called the writer and said, “Now, Chuck, on the first page there’s a problem about …” And he was interrupted, listened for about ten minutes and said, “I’ll get back to you, Chuck.” Roger then turns to me and says, “He doesn’t like my first note. Why don’t you rewrite it?” So in about five or six days I rewrote the whole script, for which I didn’t receive any credit, not that I asked for it. I helped cast it because George Chakiris, who was going to be in it, quit when he got the script. He said it was ‘immoral.’ Roger had to figure out who was going to play the part and decided that maybe Peter Fonda could do it. I remembered him looking very preppy in Lilithand wondered if he could play this biker guy, but he came into the office wearing aviator sunglasses and I thought he really looked fabulous. We gave him the part and I made sure he wore the glasses in almost every shot.

We shot for about three weeks. I did almost everything you could do on a picture. I got the laundry, made sure the lunch was there, helped find locations. We had real Hells Angels on the picture. Roger said, “Be sure you know before you get the setup where your next shot is, because the minute you have to think the crew will fall apart. Don’t think—just go! When you finish a shot, just turn to them and say, ‘Okay, we’re over here.’ Even if you don’t know where the hell you’re going, just pretend. It keeps everybody on their toes, and keeps morale up.” Meanwhile, the Hells Angels didn’t feel like hurrying up so much. Roger would say, “Let’s start the bikes now. All the bikes down the road!” and they’d just sort of leisurely kick over their engines, and after a couple tries someone would turn around and say, “It doesn’t start, man.” So then it would be a half-hour while we waited for them to get the bikes going, and we kept falling further and further behind schedule.

The last couple days we were doing a fight scene between the townies and the Angels. We didn’t have any extras, so I played one of the townies. Roger said, “Run in there.” Now, they had seen me standing next to Roger, whom they hated. Both of us wore sunglasses and they thought: sunglasses, sonofabitch director and all that. So I run in there and they just about killed me. They were kicking me, and I never prayed so much for a director to call “Cut.” After about three days of shooting the guy who was the ringleader came over to me and said, “Hey, man, I’m sorry about hassling you before.” I said, “That’s all right.” He said, “We thought you were a shit, you know, but you’re all right.” That was my first review. They’ve gotten progressively worse.

A few days before we were supposed to finish, Roger said, “We’re going to have to throw out the rest of the script and just piece it together.” I said, “Roger, we’ve only got about half the picture.” He said, “No, we’ve got three-quarters of it.” I said, “What about the other quarter?” “We’ll just have to get a second unit to go out and shoot this junk. I can’t do it. I’m not going to spend any more money.” I said, “I’d love to do the second unit.” He said, “My secretary or you, it doesn’t make any difference.” He wrapped the shoot and we went back to Los Angeles. He called me and said, “Okay, I want you to do the second unit.”

I went out and shot for a week with a full crew, then for another week with a smaller crew, and then finally the last week with just me and a cameraman, one actor and a bike. Actually for a while we were first unit, because we had Peter Fonda and Nancy Sinatra. I did a whole sequence with Bruce Dern where he gets killed up in the mountains. The only thing Roger said was, “You know how Hitchcock works.” I said, “What do you mean?” He said, “He plans everything.” I said, “Yeah.” He said, “You know how Howard Hawks works.” I said, “Yeah.” He said, “He never plans anything.” I said, “Right.” He said, “On this one be Hitchcock.” I said, “Okay.” I had a couple fights with the cinematographer who knew that I hadn’t done anything and wanted to take advantage of it. I learned a lesson because I said, “I want to shoot over there.” He said, “You can’t shoot over there, the sun’s not there.” I said, “Well, will it ever be there?” He looked up and said, “No.” I believed him. Twenty minutes later I look over and say, “Hey, there’s sun over there.” But it was too late because we’d already got the shot somewhere else, and I figured this guy didn’t know what the hell he was doing, either. So that’s how I learned to direct pictures. When I finished shooting the stuff, Roger said, “The cutter’s got too much to do. You’ll have to cut your own material together.” I didn’t have any idea how to cut, so we got a machine and a guy who knew something about it, and I started to cut. I worked twenty-two weeks on the picture, from preproduction, shooting, second unit, everything, and it was a twenty-two-week course in picture making. I haven’t learned as much since.

The Wild Angels became a very big success. It cost about $300,000 and grossed about $5 million. It was Roger’s most successful movie at that time, and he asked me if I wanted to direct my own picture, and that’s how Targets came about. Roger said, “I’ll pay $6,000 for you and your wife, but before that I want you to fix up another picture for me, same price. It’s a little Russian picture I’ve got called Storm Clouds of Venus. It’s got the greatest special effects, rocket ships taking off and landing on Venus and space stations. It’s great stuff, but there’s one problem with it. There’s no girls in it. It’s just a bunch of guys wandering around.” I said, “What do you want me to do?” He said, “I can sell it if you can put some girls in it. You can go shoot with Mamie Van Doren but I can’t afford sound.” He told me to go down to Malibu to match the existing footage. Well, you all know what Malibu looks like. It does not look like the Black Sea, which was where the Russians shot their Venus.

We went to Malibu. There were a lot of rocks in one particular place, so we shot all this stuff on the rocks. We had seven girls. I don’t know why, but I thought if they’re on Venus they have to be blond. Some of them weren’t blond but we gave them wigs. Polly designed gills of some kind because I thought they ought to be mermaids. Then I wondered how they were going to walk on the rocks. The costumes were tights with rubber things sticking off them and when they got wet they started to droop. You never saw such a group of saggy-assed sirens walking across the rocks. It was an unbelievable picture. We shot five days on the rocks. There was no dialogue, because we had no sound. We said, “How are they going to communicate?” I thought, “Telepathy!” So Mamie Van Doren would look meaningfully at one of the other girls and they would go get some fish or whatever. When all this was cut together it was totally impossible to understand, so Roger said to me, “You’ll have to put in some narration.” This went on for months. Eventually we finished the film, which was called Voyage to the Planet of Prehistoric Women. It’s a ridiculous movie. I directed ten minutes of it, that’s all.

Anyway, back to Targets. Roger said, “Boris Karloff owes me two days’ work. I made a picture with Boris and Jack Nicholson called The Terror. I want you to take about twenty minutes of Karloff footage from The Terror and shoot twenty more minutes with Karloff. You’ll be able to shoot twenty minutes in two days. I’ve shot whole pictures in two days. Then get a bunch of other actors and shoot another forty minutes in ten days and we’ve got an eighty-minute Karloff picture. Are you interested?” Being twenty-six and interested in almost anything which would give me a chance to direct, I said yes. I looked at the footage from The Terror and wondered what I was going to do with this footage of Karloff skulking around this mansion. I didn’t want to make that kind of movie. Boris didn’t even scare me very much, so I figured, “I’ll make him an actor in this film.” I was going to begin the picture in a projection room with scenes from The Terror. The lights come up and there’s Boris sitting there with Roger Corman, and Boris turns to Roger and says, “It really was a dreadful movie, wasn’t it?” Roger turns and mumbles something. I figured it wasn’t a bad idea, because if he’s a disgruntled actor then I have an alibi for all this lousy footage. That was how the film started. Then Polly said, “Why don’t we write a story about the guy who shot those people in Austin, Texas?” I don’t know if any of you remember, but in 1966 there was a guy named Charles Whitman in Texas who killed his wife and his mother and then went up that tower in Austin with a rifle and randomly killed a bunch of people for apparently no reason.

So we crosscut that with a story about an aging movie star who played in a lot of horror pictures who feels he’s all washed up and has decided he’s going to quit the business because the horror of the modern age is much worse than any Victorian horror. The tension between those two stories was what we ended up working on. It’s a bit manqué, as the French would say, but it kind of worked. We had to kill Karloff off about halfway through the picture because I only had him for two days. I showed the outline to Sam Fuller and he said, “Why did you kill Karloff off in the middle of the picture, kid?” I said, “I’ve only got him for two days.” “Don’t think about that! Ignore that! He’s the star of the picture. You can’t kill him off in the middle.” I said, “But Roger won’t give me the time.” “Ignore that!” he said. “Write the script like you got him for the whole picture. Never worry about anything practical when you’re writing a picture. When you’re directing it, that’s another problem, but right now you’re writing it.” In three hours Sam proceeded to rewrite it, quite brilliantly. After I looked at the changes I said, “But Sammy, this is a complete rewrite. I’ve got to give you credit.” He said, “Naw. If you give me credit they’ll just think I wrote the whole thing.”

I rewrote the script again and gave it to Roger, who said, “How are you going to shoot all this stuff with Karloff in two days?” I said, “I can’t.” He said, “Peter, I’m not going to pay for any more time.” So I called up Karloff’s agent and we tried several things. Luckily Karloff loved the script. I said, “I need five days.” It was a big deal and cost Roger a little extra money, but we finally got Karloff for five days and shot all the stuff you see in the film. Then we shot with other people for about twenty days. It was really about fifteen days of principal photography and ten days of second unit, which was only five people: me and László Kovács and a couple other people. We stole all the shots on the freeway. We didn’t even ask permission, because we knew they would turn us down. When the sniper is shooting the cars on the freeway, we had two cameras and a walkie-talkie system. I had some of my neighbors in cars. They said, “All right, we’re coming on the Burbank on-ramp.” I said, “Okay, okay, I see you. Okay, get ready, here we go.” And as they came by the camera I would say, “Bang!” over the walkie-talkie and they would react to the shot. László asked, “What happens if we see a cop?” I said, “Film him.” The shots of the police you see in the picture are real police. They didn’t know they were in the shot.

All together the film cost $130,000, including $22,000 for Boris. We finished it and every studio turned it down. They didn’t think it was very good or maybe they thought it was too violent. God knows what they thought, they just weren’t interested in it, except for Paramount, which sort of liked it but not enough to put up any money. Roger wanted the $130,000 that he had put out. We did a screening at Arthur Knight’s USC cinema class and invited the trade press. I said, “If you like it, please review it.” Well, they happened to like it, so they wrote reviews in the trades, and the next day Paramount called and said, “We’re still interested. Have you sold it yet?” I said, “Yep, we’ve got a deal, but it hasn’t really been closed yet.” Paramount says, “What’s the deal for?” and I say, “$130,000.” They said, “Well, we’ll make it $150,000,” and they bought it. Then there was a big internal struggle at the studio. Bob Evans and Charlie Bluhdorn were the ones who really liked it, but almost nobody else at the studio did, so it wasn’t well distributed and nobody really saw the film. The timing wasn’t great, either. You might think people would be interested in seeing a picture about random violence after two assassinations—Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy—but they weren’t. We finished shooting just before King was assassinated, and the guy who shot him used a 30.06 rifle, just like the one we used in the picture, and drove a white Mustang, which the boy does in the film.

Do you think you’ll work with Corman again?

It was a marvelous way to start, because you learn a certain discipline that you never lose. Guerrilla filmmaking is something you should all learn. You steal, cheat, lie and do anything you can to get the scene. I think that’s why many of the older directors were so good, because they had a discipline that was imposed from outside. That’s the terrible thing about having too much freedom, particularly at the start of a career. I think there’s nothing better than being told, “Look, you’ve got to do it in three days. You’ve only got this much money, so do it this way or you’re not going to get it done.” In the old days, somebody like John Ford had only so much film and that’s all. It wasn’t that he wanted to be economical. The guys in the front office said, “That’s it. That’s all you’ve got.” At Columbia for years they wouldn’t let you print more than one take. And the whole idea of “Let’s go” is important. Get the crew going. “We got this shot over here, now we’re over here.” Keep it moving, because there’s a terrible kind of lethargy and boredom that sets in on a crew. Making pictures is boring for everybody except the director, and sometimes even for him. But the more you get everybody going, the less boring it is. I was happy working for Roger. I loved it. He gave me the ground rules and then left me alone. He also loved the picture when it was finished. He didn’t give me much money, but so what?

Where did The Last Picture Show come from?

What I think Targets lacked was a sense of the performances. I began as an actor at age fifteen, and when I’m on the set I still approach everything from the actor’s point of view. Karloff was good in Targets and the boy in it was also good, but everybody else could have been better. What I really wanted to do on The Last Picture Show was concentrate on the actors, to really get good performances out of them. One other reason why I wanted to make the picture was because after reading the novel by Larry McMurtry I didn’t know how to film it. Solving the problem of how to turn this story into a film was very intriguing to me. I liked the fact that it was about a world I knew nothing about. It was quite a challenge to make a film about what was, basically, a foreign country to me.

People kept giving me Larry’s book to read and I never read it. Sal Mineo, a sweet, dear friend, gave it to me, as did two or three other people. I finally read it about two years later and liked it very much. I wanted to do it but I couldn’t get the rights. The producer Bert Schneider, who had liked Targets, said to me once, “If you ever want to do a picture, let me know.” A lot of people say that, so I didn’t believe it, but I called him up and said, “Hey, were you on the level about wanting to do a picture?” He said, “Yeah.” I said, “Well, I read a book I liked called The Last Picture Show by Larry McMurtry. Go get it and read it.” I wanted to see if he was really on the level. About a week later he called and said, “Well, I read the book. Let’s make it.” I said, “Fine, except this other guy owns the rights and I think he’s got some pretty bad ideas how to make this thing.” Bert said, “How do you want to make it?” I said, “I just want to make the book.” He said, “That’s what we all like, isn’t it?” So he got the rights and we made it. It was really pretty simple.

Larry wrote a draft, which I rewrote. The trouble with Larry was that he really didn’t like his book as much as I did. He kept changing the script. I would say, “Larry, this wasn’t in the book.” He said, “No, it’s better.” I said, “No, it’s worse,” and I would change it back to the book. It’s funny correcting the writer himself. He had written the book in five weeks out of a kind of anger, and I don’t think he felt the same thing I did coming fresh to it. The script really was pretty much the book with parts cut out. We really could have made the picture another hour longer.

How did you come to cast Ben Johnson in the film?

I couldn’t think who could play the part of Sam the Lion. I went to Nashville and interviewed old country-and-western singers, thinking maybe I’d find some great old faces there. Then one day I thought, “Ben Johnson!” But he didn’t want to do it. He said, “Peter, there are too many words. I can’t say all those words.” So I called John Ford and said, “I’ve got this wonderful part for Ben and he doesn’t want to do it. He says there’s too many words.” “Oh, Christ,” he says. “Ben’s always been like that. When we were shooting Yellow Ribbon Ben would come on the set and go over to the script girl and ask, ‘I got any words today?’ If she said yes, he’d go and sulk. If she said no, he was happy. All he had to do was ride.” Ford says, “Where is he? I’ll call him.” So about an hour later Ford calls me back and says, “He’ll do it.” Then Ben calls and he says, “Christ, you got the old man on me.” I said, “Well, I just want you to do this picture.” So he came in about three or four days later and sat down in the office. He had the script in his hand and said, “Pete, I just don’t think I can do this for you, boy.” I said, “Ben, you’ve got to do it.” He says, “Why do you keep saying that?” I said, “Because there’s nobody else that could do it.” He said, “Oh, shit, you can get ten other guys.” I said, “No. You play this part and you’ll win the Oscar.” Finally he slammed the script shut and said, “All right, I’ll do the goddamned thing.” I said, “Look, we’re going to start rehearsing Thursday.” He said, “What have I gotta do?” I said, “You don’t have to do anything but read through the scenes. I’d like the cast to meet you more than anything else.” So on Thursday I introduce him to everybody and say, “Let’s just read your scene.” So we start to read and he’s got the script closed. He doesn’t open it because he already knows every line he’s got in the thing, letter perfect. We finish and I say, “You know, you’re a sonofabitch.” He says, “Why?” I say, “What the hell do you mean, telling me you don’t know how to read words? You didn’t have to learn the lines by now.” He said, “Well, Pete, I’m not too good at reading, so I just figured I’d better know ’em.” Anyway, he did win the Oscar. The topper is that three years later I’m talking to him about a picture we wanted to do with Duke Wayne and Jimmy Stewart, and he says, “I like it, but there’s not too many words in there for me.”

Can I ask you a blunt question? You’ve worked with a lot of very good actors. Was Cybill Shepherd hired on the basis of her looks?

No, she wasn’t hired on the basis of her looks. I was in New York casting and she came in and took off her shoes and sat on the floor next to a kind of a pot with a couple flowers sticking out of it. I said, “What do you do?” She said, “I go to college.” “Where do you go to college?” “I go to Hunter.” “Well, what are you taking?” “English literature.” She’s behaving like she doesn’t give a damn about being there, and I asked her which authors she likes, and she says, “Dostoevsky.” “What have you read of his?” Long pause. “I can’t think of anything right now.” But as she said it she played with a flower. There wasn’t any kind of feeling that she had been caught short. It was as if I was the dummy for asking such a stupid question. It was the most wonderful reading I’ve ever heard. It turned out she was just nervous and that’s the way she acts in those situations. She gets rather quiet and shy but it comes out as very cool. But when she touched that flower I expected it to wilt, and I thought to myself, “That’s the character!” I hadn’t understood the character until that moment. Jacy should be a girl who’s kind of destructive to men, but not on purpose. She just flits from flower to flower and they wilt in her wake, but it’s not like she goes out and says, “I’m going to kill that guy.” That’s the character we evolved, but she gave it to me just by touching the flower in the audition.

I think one of the finest moments in The Last Picture Show is the last shot with Cloris Leachman just before you dissolve to the pan.

You mean when she’s trying to talk to him and she can’t quite get anything out? Essentially, she had some answers to this situation. She seemed to glimpse the sun through a cloud and was trying to find the words to say it. This character is not an eloquent woman, so she lost the words. But she knew that it would all be okay. I was telling her all this as we were doing it. She was great, though the producers wanted me to cut the whole last sequence with Cloris and Tim. They thought the picture should end on the road. I said, “I only made the picture so I could have that scene.” It’s the best scene in the picture. I had to cut some other things as a sacrifice. You have to give them something so you can keep the stuff you like. That’s true in life too.

You spoke earlier of studying with Stella Adler. Can you say what she taught you?

I was involved in many theater productions as an actor and stagehand and dresser, perhaps forty of them, before I ever directed. Everything I know about communicating with actors I learned from Stella, things I could fall back on when my instinctual approach failed me. Instinct will take you only so far. Because she taught acting in such a complete way, she was also talking about directing. I found the first six months of her class fascinating but just didn’t understand what she was talking about. You needed to be eighteen to get into the class but I lied because I was only sixteen. After a few months, it all clicked into place and the basic idea of what theater and acting are—this heightened reality rather than mundane naturalism—really began to make sense to me. Directing actually started for me because I was sitting around with five actors from Stella’s class and I said, “Why don’t I direct you guys in a scene?” Usually scene class would be a two-character scene or a monologue, so having five actors in a scene all interacting was unusual. We put it on for the class and when it was over Stella stood up and said, “Bravo darlings! But you’ve been directed. Who directed you?” They all pointed at me at the back of the room. She turned to me and said, “Brilliant, Peter!” So I figured I wasn’t bad at this.

Did you have any contact with Sanford Meisner or Lee Strasberg?

I was in Strasberg’s class once, but that’s about it. I’m not a big fan of his. I’m very much from the Adler school, and Stella didn’t think Strasberg was a good teacher. Strasberg was a perversion of the Stanislavsky method, and Stella would be the one to know because she’s the only person in the United States who actually studied with the man himself. She heard it from the horse’s mouth. Stanislavsky said that acting is fifty percent external and fifty percent internal. Strasberg completely eliminated the external and was interested exclusively in the internal, which is not a good thing for acting.

Did your time as an actor help you as a screenwriter?

Acting is very much a part of writing. With some scenes I’ll act out the parts myself and transcribe what I say.

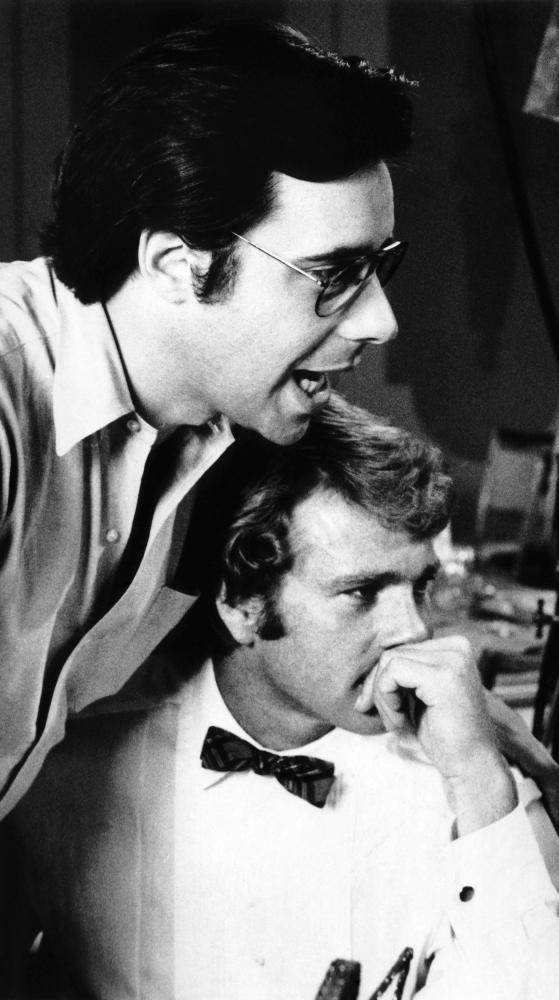

Was the idea for the slapstick What’s Up, Doc? your own?

Warner Bros. came to me and said, “Would you make a picture with Streisand?” They had a script they wanted me to do called A Glimpse of Tiger, but it wasn’t the kind of film I wanted to make. Picture Show hadn’t even opened at that point and only two people had seen it. One was Steve McQueen, who wanted me to make The Getaway. He came into my office after seeing the film and said, “I’m just an actor, man, but you’re a filmmaker. You only made one mistake in that picture.” I said, “What was that?” He said, “You never should have cut away from the diving board.” If you remember, there’s a scene in Picture Show when Cybill strips at the swimming pool.

The other was Barbra Streisand and she wanted to work with me, so John Calley, the head of Warner Bros., said, “So you don’t like this script. What would you like to make?” I said, “A screwball comedy, like Bringing Up Baby, with Barbra. A square professor and a daffy dame who breaks him down live happily ever after.” He said, “Do it. Who do you want to write it?” I said, “Well, I worked with Benton and Newman at Esquire.” Calley said, “Great, they just did a picture for us.” I called them and they explained they were starting another film in three weeks. I said, “If Ben Hecht and Howard Hawks can do Scarface in eleven days, we can do this in three weeks.” We worked for three weeks and ended up with a draft that needed a lot of work. I rewrote it a little and had a reading with Ryan and Barbra. I read all the other parts and talked my way through all the action sequences, and at the end of it they both committed to it. John Calley suggested we bring in Buck Henry to rewrite it, who said, “You’re going to hate me but I don’t think it’s complicated enough. You need another suitcase.” So we added the whole Top Secret suitcase which was inspired by the Pentagon Papers story. That’s actually why we cast Michael Murphy, because he looked a bit like Daniel Ellsberg. Buck rewrote the script, which is more or less what we shot. We made up some of the jokes as we were planning and shooting it. For the party scene in the millionaire’s house, all Buck wrote in the script was: “There is now a fight which will be brilliantly staged by the director.” That was it. Thanks a lot, Buck.

The film ended up being the second-biggest hit of the year, after The Godfather, which actually I turned down because I didn’t want to make a Mafia film. There was an early, glitzy screening of What’s Up, Doc? and the audience seemed to be resisting it. They weren’t loose enough for a film like that. It’s like everyone was sitting there asking themselves, “What is this?” There had been some laughs but it wasn’t as warmly received as it would later be by the public. About ten minutes in, John Cassavetes stands up, in the middle of the picture, turns to the audience and shouts, very loudly, “I can’t believe he’s doing this!” The place broke up, and from then on theemy loved it. John and I became friends after that. It’s my favorite review of any film of mine.

It looks like you had fun making What’s Up, Doc?

What’s Up, Doc? was the most fun of any picture I’ve ever made. It was absolute heaven from beginning to end. I didn’t give a damn if we ever made the picture, an enviable position to be in. This hasn’t been the case on every picture I’ve made, but you must never give a damn if the whole thing falls apart. “It doesn’t matter—we’ll do something else”: that’s the only way to do pictures, because when you start caring they kill you. When you start saying, “If I don’t make this picture I’m going to die,” they will make you pay.

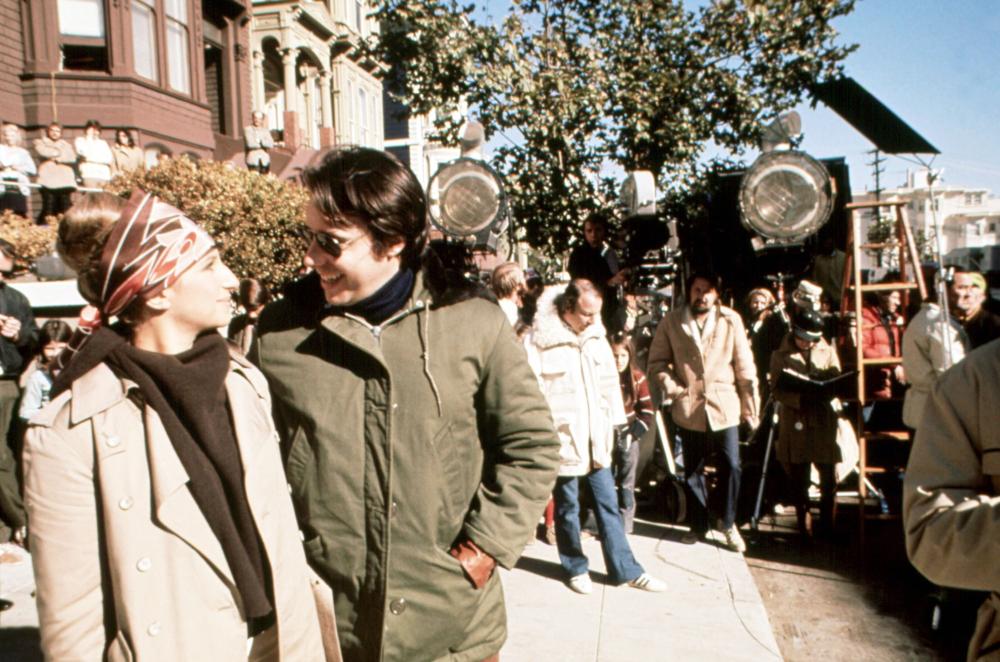

I remember Barbra Streisand told me before we did the picture, “I’ve never been directed. Nobody’s ever directed me in a picture.” I said, “Well, you’re about to be directed,” and I directed the hell out of her. She wouldn’t listen to me a lot of times. She wouldn’t cut her nails, for instance. I said, “Barbra, this girl is a college kid and she wouldn’t have these movie-star nails.” She said, “I’m not going to cut my nails.” I said, “Jesus, first of all, your hands look better without the long nails.” She said, “No, they don’t. I have stubby fingers.” I said, “You don’t have stubby fingers.” She happens to have very nice hands and her fingers don’t look stubby at all. But she has these silly long nails, so I made her carry something all the way through the picture. She’s got a suitcase or a coat over her arm or something so I wouldn’t see her goddamn nails. But generally we really got along and worked well together. The director is an actor’s first audience and she wanted to please me. She knew exactly what I wanted.

We took over San Francisco and wrecked a couple of streets and got in a lot of trouble. We had a hell of a scene when all the cars go into the water at the end. The first guy that went in was the Volkswagen. They told me Volkswagens float, but it ain’t so. This thing went down like a stone, and it was very deep. The guy drove in at about seventy miles an hour without an oxygen tank. We were all standing there dying because the guy didn’t come up for a minute, two minutes. Finally he comes up having escaped through the windshield which luckily came in on him, because he couldn’t get the door open. We had seven or eight cameras on those particular shots, so if one camera malfunctioned we would still get it.

John Ford gave me a very good piece of advice. He said, “Never rehearse action.” I said, “Why not?” He said, “Somebody could get hurt.” It’s a cryptic remark, as all of Ford’s remarks were, but it makes sense. What you do is discuss everything that can possibly happen and what you want and what you’ll take if you don’t get that, and then you do it. Usually you get elaborate pieces of action on the first take because nobody wants to do it again, and they all work like hell to get it right. One of the last shots in The Last Picture Show is where all the guys are standing around the truck and the kid is lying on the ground dead, and it builds until Tim Bottoms yells out, “He was sweeping, you sons of bitches!” He picks up the body and carries it to the marquee of the theater. I wanted it to be without a cut. I didn’t want the camera to leave him from the moment he said “He was sweeping” to the time he carries the body over and walks away. It was about fifty feet from there to the theater, so he had to pick up the body and carry it, and the camera was on a truck. It was a complicated shot for the actor because of the emotion and very complicated for the crew because there was a zoom involved which I wanted to hide. We set it up before lunch and I talked to Tim all through lunch. I was trying to find out what he was going to do without telling him what to do. This was a line that I wouldn’t let him rehearse. I knew it was a line I only wanted to hear once. That’s a movie-acting thing. It’s not true on the stage, but there are certain lines in a movie that should only happen once, because the minute you have to do it again it becomes mechanical. That first emotion is very important for certain moments. The crew came back from lunch and I said, “We are not getting a shot of a guy carrying a body across the street. We are shooting a bridge being blown up. There is only one camera and we’ve only got one bridge. I don’t want any mistakes from you guys. No excuses.” So we did the shot and we got it, thank God. Luckily Tim was superb and the crew was superb. As a matter of fact, to prove my point we actually did the shot twice. The second one was technically better—but the performance wasn’t there. The first one broke your heart. It’s the only time I’ve ever been moved to tears on a set by an actor.

What did Barbra Streisand mean when she said that she hadn’t ever been directed before?

Most directors have no idea how to direct actors. It’s rare that they do. William Wyler would just say, “Do it again.” Very few of the older guyshad any theatrical experience, but they did have a sense of what they wanted.

Did you write the script of Paper Moon?

I was sent a script called Addie Pray which was based on a book. It wasn’t too good but there were two scenes in it that were wonderful: the café scene and the scene on the hill with Trixie. Those two scenes were the only two scenes that remained after the rewriting. But they were so damned good that I said to myself, “Jesus, I could do something with this.” I saw the whole thing as some kind of anti–Shirley Temple movie. I read the book and there were some things that weren’t in the script that I put back in and some things that I took out. We didn’t come up with an ending until we shot it. I finally came up with it the night before we shot it. We had that great location, that wonderful road, and we knew she was going to come after him but we weren’t sure how, so I came up with that line about the $200, which got me out of a lot of trouble.

I came up with the title Paper Moon, which nobody at Paramount liked. I thought Addie Pray sounded like a snake or a lizard or something. They all said, “Why do you want to call it Paper Moon? What’s it got to do with the picture?” I said, “What the hell does it matter what it has to do with the picture? It’s a good title.” I said to the writer, “We’ve got a problem. You know those paper moons that you sat in at carnivals and they took your picture? We’ve got to put a scene in so they’ll think there’s a reason for the title.” I called up Orson Welles who was in Rome and said, “Hey, what do you think of this title?” Because this is long distance to Rome and I wanted to make sure he understood, I said, very loudly, “Paper Moon.” There was a long pause, and he says, “That title is so good you shouldn’t even make the picture. Just release the title.”

How did you work with Tatum O’Neal in Paper Moon?

With great difficulty.

Did you have to overcome some difficulty with her father?

Jesus no, I had to keep Ryan from killing her. “Goddammit, Tatum, would you learn your lines? Goddammit, I’m not going to do it again with her! Shit, we’ve done it twenty-eight times! Get the lines right, Tatum! Peter, I can’t do it again. I did Peyton Place five thousand times and I never went through anything like this!” This is on a road in the middle of Kansas with nothing anywhere but Kansas and the car and this rig that we had pulling the car with the camera on it and twelve people hanging around. It was a scene between Ryan and Tatum which played without a cut, and it was the end of the first act where they have this big argument about the Bibles. It’s really the scene where they sort of admit that they care about each other without saying it or admitting they’re going to stay together. It’s one of those scenes where they don’t say what they mean but hopefully you get the point. I wanted it to be without a cut with them driving along, so we figured the scene would take about a mile and a half to play, and we only had about a mile and a half where the road was good because after that you started seeing something that wasn’t of the period. Two miles down the road there was a place where we could turn around and come back, but turning around took five or six minutes because the road was so narrow. So since it had to be without a cut, if they started down the road and after about three lines somebody blew it we’d have to go two miles and then turn around and go back. We did it twenty-five times the first day. I remember putting my arm around Ryan and walking up the road while I calmed him down. I got him to do it another few times and we still didn’t get it. The next day it rained, and the day after it rained and we shot some other stuff, and a few days later we came back and did it again. We got it the second day on something like the sixteenth take.

Tatum was eight years old and didn’t have any idea what the hell we were doing, and she sort of cared less. She’d never had any discipline in her life. She was in a world of her own, and sometimes her world and the one we were trying to create on screen didn’t necessarily mesh, like the time we were shooting the carnival scene. It was a night scene so it took us about three hours to light it. Tatum got there about five o’clock and did what any kid would do. She started riding the Ferris wheel, eating popcorn, eating candy corn, eating peanuts, and by the time we were ready to shoot she was sick. She was on the floor. “I told you not to eat,” said Ryan. “I told you, you idiot.” “Oh, Daddy!” “Get up!” Ryan and I sort of alternated on who was going to be yelling at her. You had to scare her into doing it right. After about five weeks she really got into it and started to enjoy the shooting and was much better.

When Ryan’s character says, “I ain’t your pa,” I always figured from the first frame he really was her father. He’s just not going to cop to it. When we were casting the film, Paramount told me John Huston had wanted to make it with Paul Newman and his daughter. Polly said, “What about Ryan’s daughter?” But Paramount said they wouldn’t use Ryan under any circumstances because he’d had an affair with Ali MacGraw on Love Story when she was married to Bob Evans, who was head of the studio. I said, “I won’t make it with anyone else.” What’s Up, Doc? was still playing in theaters and was a big hit, so I forced the issue with Paramount. It wouldn’t have been good for their stockholders to turn the film down.

How did you come to make Daisy Miller?

I read a script of Daisy Miller that was pretty bad, but when I got to the end and all of a sudden she died I was very moved. So I read the original Henry James story and thought, “I ought to make this.” In other words, the ending of the story made the whole thing really mean something. That’s the case with most stories: it’s how it finishes that matters. What does it all add up to? Deciding to do something really comes down to whether it moves me emotionally, or whether it makes me laugh. I made Daisy Miller because it moved me. What persuaded me to do it is the complete misunderstanding of Daisy Miller by the young man. He’s so in love with her but absolutely doesn’t get her. He judges her. It’s why he’s named Winterbourne. He’s as cold as ice, certainly when compared to her vibrancy. It seems to me that one of the prevalent problems in society is that men don’t understand women. Men trust what they shouldn’t and don’t trust what they should. Winterbourne is also a complete jerk who thinks he’s superior to this young American girl who is shameless and stubborn, but also a quite innocent flirt. The line on the poster was “She Did as She Pleased.” Daisy flaunts Italian custom by being seen walking in public with this man, but he just doesn’t understand where she’s coming from. James puts it very well when he has Winterbourne say at the end of the story, “I have lived too long in foreign parts.”

We had Freddie Raphael write another version of the script based on a few conversations we had about making it darker, more dramatic. But that was a mistake, because Freddie wrote a Dostoevsky version and it just didn’t work. So I went back to the book and rewrote every scene, and ended up keeping only a couple of his ideas, like setting the tea scene in the baths. The script went to arbitration and he ended up getting credit on the film. They offered me “Additional Dialogue” and I said, “I’m not going to be the Sam Taylor of my generation.” Sam Taylor was the guy who took credit on a version of The Taming of the Shrew. After “Based on the play by William Shakespeare” it said “Additional Dialogue by Sam Taylor.” My original plan was to play Winterbourne myself and have Orson direct, but he didn’t want to do it.

Why do you think the film was so badly received?

I don’t know. I’m very proud of it, and I think everybody is good in it. I think it’s beautifully shot. I think the script is very faithful to the book and I think the book is wonderful. People don’t realize that almost all the dialogue in the picture is by Henry James. I would just change certain words that were a little bit too formal, things like “I shouldn’t think so” instead of “I wouldn’t think so,” because Daisy wouldn’t say “I shouldn’t.” There were extraordinary words that came up in the dialogue that you thought wouldn’t be used during that period. At one point she says, “Did you ever see anything so cool?” That’s such a fifties or sixties expression, but she said it. It’s in the book from 1875.

People find it difficult to accept a character like Daisy Miller in that milieu. I could tell a western with the same basic plot: an Eastern girl comes to the West and doesn’t understand the codes of the West. If you put her into a western nobody would have any difficulty believing that character. But the minute you put her into a European milieu, which is sort of sophisticated and highbrow and artistic, people find it hard to believe that anybody could be that crude. But that’s the point of the story, and if you read it again you’ll find she’s described as crude, vulgar and annoying. She was supposed to be that way, yet you were supposed to like her anyway. If you don’t, I’ve failed in some way. But I do think that in ten years you’ll like it better, when you forget about who Cybill Shepherd is, when you forget about the fact that she’s my girlfriend, when you forget about the fact that she was a cover girl.

It’s amazing, when you see movies again, how they change. I’ve seen pictures that I adored ten years ago and now think are crap, and pictures that I hated ten years ago and now think are masterpieces. Actually, what changes is you. But it is true that pictures have a way of changing their shape and color. That’s why it’s so difficult to be a critic. It’s almost impossible to guess what’s going to last. It sounds like I’m being very defensive, but really I’m talking here today about my films as though somebody else had made them. We’re sitting here looking at Daisy Miller in terms of what the director intended to convey and what he achieved. When five or six years have passed I might go back and look at a film I made, and it either works for me or it doesn’t, just like I might run a picture by Mizoguchi or John Ford or Lubitsch or Billy Friedkin.

With Daisy Miller, which I think is one of the most beautiful films I’ve ever seen, were you influenced by anyone when it came to your camera setups and the color and the composition?

Mainly my father, who was a painter. He worked at home because he couldn’t afford a studio, so from the moment I was born I was surrounded by composition and color and images. It must have had a profound effect on me. He was influenced by the postimpressionists, but because of his Serbian heritage his work had some kind of Byzantine overlay, which meant the colors were brighter. Daisy Miller is one of the few pictures of mine I can look at and not feel like I actually had anything to do with it, which is nice. Looking at your own work is like looking in the mirror. I was in the Plaza Hotel some years ago with Ryan O’Neal. We were both staggering out in the morning for some sort of interview, and there was a mirror next to the elevators to let you know how you look. Ryan was already standing there looking in the mirror. I came running up and said, “Oh, shit,” and he said, “What’s the matter?” I said, “I always think it’s going to be better.” He said, “That’s funny. I’m always pleased at how much better it is.” That’s an essential difference between actors and directors.

You had the great fortune of knowing Fritz Lang and John Ford. Do you think those relationships helped you with your own filmmaking?

There’s a fine line between being influenced by these guys and stealing outright from them. All directors steal from each other. I was talking to Howard Hawks about the shot in Red River when the cloud comes in and covers the funeral. I said, “That’s a hell of a shot.” He said, “Well, you know, sometimes you get lucky and get one of those great Ford shots.” I said, “Do you mean you thought of it as a Ford shot then?” He said, “Oh, sure. We all said, ‘Let’s get that Ford shot.’ ” I asked him if Ford had influenced his westerns and he said, “Well, Jesus Christ, Peter—I don’t see how you can make a western and not be influenced by John Ford!”

I was fortunate because I got out to Los Angeles in 1961. Many of the great directors of the early period were still alive then, and some of them were even still working. I tracked them down and asked them as many questions as I possibly could. John Ford once yelled at me and said, “Jesus, can’t you end a sentence with a period? Have you ever uttered a declarative sentence?” Almost all of them enjoyed talking about their work, even someone as recalcitrant as Ford. He could really talk once you got him going. It must have been gratifying that such a young guy was asking them so many questions. They were all aware that even though I was writing for Esquire I was actually a theater director and an actor. This was the trick to it all, that they knew I wasn’t a real journalist but that I was in the business.

It was like putting myself through a unique film school that had as its faculty all the great directors. Almost all of them began in the silent era. I think one of the biggest problems facing movies today is that we’ve lost touch with silent cinema. They are the foundation of everything that came afterwards. One of the main things I learned from the older directors is not to let the dialogue dictate how you make the picture. Hitchcock said most pictures are simply pictures of people talking, and that’s become more and more the case. I like what Allan Dwan said, that when we switched from silent pictures to sound, the whole artistry was gone. He said, “Every time I finished a talking picture I’d run it silent. If I could pretty much follow the plot, I figured I’d done a good job.” Chaplin has a great line about this: “Just when we were getting it right, it was over.” It’s true that around the time silent cinema ended, they were becoming flawless at telling stories visually.

For me, the material, the story being told, dictates the style. I feel that one of the dangers in picture making is that style has become more important than content. On the other hand, if the content is very good and the style is no good, it’s still no good. If there’s no substance, a film will always be shallow. But substance with no craft is equally problematic.

Was it you who pioneered the idea of going back and interviewing the old directors?

The French did it first. Chabrol, Truffaut, Rohmer, Rivette and Godard were all interviewing the old-time American directors for Cahiers du Cinéma. I read the magazine in the late fifties and early sixties, and it seemed perfectly natural to go and interview those people I was interested in.

Did you ever think about going to Europe and doing for French and English directors what you were doing for American filmmakers?

My focus was on American movies and directors because I was going to make American films. I went to see Bergman and Antonioni, but that wasn’t my predilection. I think something that has hurt American cinema of late is that younger filmmakers have gone after Antonioni and Fellini. Such pretension! Where’s Raoul Walsh when we need him?

Had you really seen all the films you discussed with the directors you interviewed?

I think I saw all but one of Hawks’ films, and I think I saw all of Hitchcock’s films, but with someone like Ford a lot of his films are lost. I certainly didn’t see all of Allan Dwan’s films, because he made so many. But remember that film culture in New York in the fifties and sixties was a vibrant one, and there were a lot of opportunities to see rare films back then. People were starting to take film very seriously. I was marginally involved with a group of filmmakers and avant-garde artists that became known as the New American Cinema group, people like Lionel Rogosin and Jonas Mekas. Adolfas Mekas asked me to be in his film Hallelujah the Hills, but I turned him down because of the nudity. I didn’t want my ass all over the screen. I was interested in seeing avant-garde films, but knew that wasn’t the kind of work I wanted to make myself. By the time I was about twenty I had sketched an idea for a film I wanted to make called The Land of Opportunity, about a young couple in New York who get everything for free. They either steal it or somehow promote it for free. I just had the idea, and never even wrote the script. Years later I ended up using some of those ideas in What’s Up, Doc?

I would go to Amos Vogel’s film club Cinema 16 all the time and remember vividly seeing some memorable movies there, like Gold Diggers of 1933 and Hawks’ Twentieth Century, for the first time. I worked for Dan Talbot for a couple of years at the New Yorker Theater on the Upper West Side, which could hold something like a thousand people. Dan was the first person to show classic American films rather than foreign films, which the Thalia and most of the art houses were doing. He was following the Cahiers lead and started an American revival house which was a very influential theater for a number of years. I advised him somewhat on which pictures to book, and curated a number of shows like The Forgotten Films, where we ran fourteen double bills in two weeks—twenty-eight pictures in fourteen days which hadn’t been seen on the big screen for thirty years. I had help from Andrew Sarris and Eugene Archer, and wrote all the program notes. In the program note I did when Dan revived Orson’s Othello, which had hardly been seen in New York at all, I called the film “the best Shakespeare film ever made.” This was hardly the conventional wisdom at the time, and I got a call from Richard Griffith, head of the Museum of Modern Art film library, who asked me if I wanted to curate the first-ever American retrospective of Orson’s work at the museum and write the accompanying monograph. I said, “Why me? Why don’t you do it?” He said, “I don’t really like Orson Welles very much, but we have many friends and colleagues who do and feel the museum should do this. We think you would be the right person to organize the retrospective.” That became The Cinema of Orson Welles, my first book.

Why didn’t you interview him at that time?

He was in Europe shooting The Trial. I sent two copies off to some address in Europe and didn’t hear a thing for seven years, not until 1968, after I’d directed Targets. After the film had opened I get a phone call. “Hello, this is Orson Welles. I can’t tell you how long I’ve wanted to meet with you.” I said, “Hold on, that’s my line. Why did you want to meet me?” He said, “Because you have written the truest words ever published about me.” He paused for a few seconds and added, “In English.” Then he said, “Meet me at the Beverly Hills Hotel tomorrow.”

Your written work seems almost anti-academic.

I’m not consciously anti-academic, it’s just not in my nature. Only occasionally do I explain what a film “means.” I don’t like to get philosophical about any films, even my own. I’m much more of an instinctual artist than people give me credit for, because they think I’m paying homage to various things with my films. One critic said that Paper Moon is a homage to thirties filmmaking. What nonsense! The film is set in the thirties, but I never saw a single film like that made in the thirties. I was in London a while ago and a taxi driver said, “I love Paper Moon. It’s such a celebration of family.” Well, that’s not what I intended at all, but I’m not going to tell him that and disappoint him. His point of view is entirely valid. There was a Renoir series a few years ago here in town. I went over to his house afterwards and said, “Jean, I saw Boudu Saved from Drowning. What a wonderful film that is!” He was such a humble and generous man, and he said, “Oh, thank you very much. You’re very kind.” I said, “Do you like the film?” He said, “Well, you know it was made in the early days of sound, and some of the sound is not so good. The music recording is not so good. We had no money and had to buy film stock as we went along, so some of the picture doesn’t match from shot to shot. Sometimes the cutting is a little too fast, and sometimes the cutting is a little too slow.” He went on and on. “But I think that perhaps it’s my best film.”

As Renoir once said in an interview with Jacques Rivette, “When we have achieved total realism, we will have achieved total decadence.” My interpretation of that is that today, with special effects, you can do anything on film. But who cares? The magic is gone. The audience knows it’s all just one big expensive box of tricks. It used to be exciting when Douglas Fairbanks jumped up onto a table. The whole idea of suspension of disbelief has evaporated. Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd did all their own stunts, which is what makes them so brilliant. Someone once complained to Chaplin that his camera angles weren’t interesting. He said, “They don’t have to be. I’m interesting.” If you watch Astaire and Rogers dancing, there’s hardly a cut. Long takes. Part of the greatness of movies is showing something happen in real time. Today special effects are getting so good that who knows what’s real? And all the cutting and hand-held camera that goes on just makes you aware of the process. What does it add? Certainly not realism.

What do you make of Easy Rider? It seems to be the antithesis of your own work, which looks quite conservative in comparison.

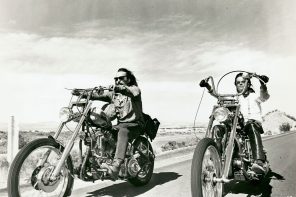

I don’t think “conservative” is the right word. I’m more of a classicist. But don’t forget that The Last Picture Show had nudity and showed teenage sex in a way that had never been shown before. It was quite a radical film for its time even though the story was told in a classical style. Easy Rider really began with The Wild Angels. Peter Fonda basically plays the same character in both films. Brando in The Wild One hadn’t done well, and The Wild Angels was the first really successful biker picture. It started a whole genre and without it there would be no Easy Rider. Peter and Dennis Hopper came to Roger Corman and asked if he wanted to make Easy Rider, but Roger turned it down because they wanted half a million dollars. Of course the two of them ended up winning the prize at Cannes and making a fortune.

Did you come up with the original idea for Nickelodeon?

It was a pet project of mine because I found the whole silent era so fascinating. Film is the only art form that was born within our lifetime. It’s a complicated, wonderful and horrible medium, and I wanted to tell a story about how and when it all started. It’s a moment full of great innocence, something I think is reflected in the film. All the stories in Nickelodeon are largely true because they were told to me by the directors who had been making films back then, people like Leo McCarey, Allan Dwan and Raoul Walsh. For example, Ryan O’Neal becoming a director comes directly out of what happened to Allan Dwan. A director went missing, so Dwan sent a telegram to his boss explaining what had happened, and received a reply telling him that he was the new director.

To be honest, I don’t much like the film. It wasn’t the picture we wanted to make. Too many compromises, like having to make it in color, and the casting. I wanted a younger cast, but the studio wanted big star names.

What are your thoughts on music in films?

I think that essentially I’m cheating if the music in a film accentuates or embellishes the action. It seems to me that the visuals should do absolutely everything. Too many movies today are told through the music. What I do like is when the music plays against the visuals, like if you have fast-paced images and something going on musically which acts as a counterpoint, or somebody playing a funny song in a sad scene.

It sounds as if the singing in At Long Last Love was recorded live.

That was a folly of mine. It was an ambitious but flawed film for which I can only blame myself. My favorite musicals are the Lubitsch films of the late twenties and early thirties. I fell in love with those pictures, and along with a book that Cybill gave me, a collection of Cole Porter lyrics, they’re the ret see how you can make a western and not be influenced by John Ford!ason I made At Long Last Love. One of the things that made The Love Parade and The Smiling Lieutenant so exciting was that you knew they were singing live. The orchestra was right off-camera. They couldn’t mix sound in those days, so they had to record everything at the same time. I remember Hitchcock telling me he shot an insert of a radio and there was an orchestra playing off-camera because they didn’t have the ability to record it later and mix it in. He might have been exaggerating, but for me it made sense not to postsynch, because the immediacy of the whole thing would be lost. I couldn’t stand the thought of recording the singing first and playing it to the actors as they’re being filmed. I wanted to make a musical where they were acting the songs and singing them live. Everybody thought this was crazy, but I was riding high at the time.

It became a huge problem, because we couldn’t afford an orchestra on the set, so Fox spent quite a lot of money to develop a tiny speaker that fit into the actor’s ear. They each had an antenna combed into their hair that could pick up an electric signal sent from an electric piano, so on the set the actors were hearing the music. Actually, none of them were really singers, although that was the fun of it. Remember the scene with Burt Reynolds and Cybill in the swimming pool when she laughs so hard she can’t sing? That’s just what I wanted. The point is that these people are superficial. They can’t speak, which is why they’re always singing. It’s not an Astaire/Rogers homage, it’s about people who aren’t singers and dancers but would like to be, just like me. They can only express themselves through songs written by someone else. I often sang to girls because I didn’t know how to put it into words of my own. It sounds corny to say “I love you,” so why not sing instead [singing] “I’ve got a crush on you, sweetie-pie”? So it was a rather personal film for me, and the Cole Porter song that made me want to make the movie is the first scene I wrote but is one of the last scenes in the film [singing]:

I loved him but he didn’t love me

I wanted him but he didn’t want me

Then the Gods had a spree and indulged in another whim

Now he loves me but I don’t love him.

I read that lyric before I knew the tune and said, “That’s the movie I want to make.”

What was the concept behind the Directors Company?

I got a call from Francis Coppola saying that Charlie Bluhdorn of Gulf + Western had the idea that we three—Coppola, Friedkin and I—get together and make a bunch of pictures and then go public and make a lot of money. Francis, Bill and I flew to New York and had a meeting with Bluhdorn. I remember that Frank Yablans, the head of Paramount, walked in and hated the whole idea. “Why don’t you just give them the studio?” he said. For any picture that cost up to three million dollars we could make anything we wanted. We didn’t even have to ask the studio or tell them what it was. For a million and a half or under we could produce a film directed by someone else. Again, we didn’t have to tell them what it was. To put things in perspective, Paper Moon cost $2.8 million and The Last Picture Show cost $1.3 million, so I didn’t think we needed much more. The other thing was that our contract said we didn’t have to cut the films for television, which was important to us.

I was looking forward to making all kinds of films, including one with King Vidor called The Extra about James Murray, the actor in his film The Crowd, and a film with Orson based on a Joseph Conrad novel. The whole thing really was a great idea on paper, and we should have made a lot of pictures, but Francis and Billy ended up wanting more money up front. The back end was great but the money up front wasn’t. I think there was a limit of $300,000 per film for the director, and because of that the whole thing fell apart fairly quickly. Everyone in the company ended up doing well on Paper Moon, which was the only picture that made money, because I threw the film into the mix to jump-start the company. I had a deal to make that film long before we formed the Directors Company but thought it would be a good idea to sweeten the pot for everyone. That was a big error on my part, because I ended up losing a lot of money.

Do you shoot lots of cutaways for protection?

Probably the central thing I heard from almost all the old directors I spoke to—Ford, Hawks, Hitchcock, Lang, Dwan, McCarey—was that they basically cut in the camera. Generally the old masters didn’t shoot coverage. I saw Ford put his hand over the camera lens one time as if to say “That’s enough.” These guys knew where they were going to cut when they were shooting the scene. Being young in the business, I assumed that was the way everybody did it, but found out later that some directors, like Capra and Stevens, would shoot a lot of coverage. I learned from Ford, who said, “Just shoot what you need, kid, and don’t give ’em anything they don’t need and that you don’t need.” Ford was shooting How Green Was My Valley and there’s a great shot during the marriage scene. Maureen O’Sullivan’s character is marrying someone she’s not in love with, and they ride off in a carriage. It’s a long shot, and the camera pans them off and holds on the minister, Walter Pidgeon, standing under a tree. This is the man she’s really in love with. It’s a long shot, and the cameraman said to Ford, “Jack, do you think we should grab a close-up of Walter under the tree?” Ford said, “Oh no, Jesus—I mean, they’ll just use it!” He meant that the editor, who he had no control over, would use the shot just because it was there. Part of my training was to think only in terms of what is needed. The time to make up your mind about what the scene is about, and how and where it should be played, is on the set during filming and not in the cutting room, otherwise you’re wasting time shooting things you’re not going to need. You can cut almost anything together in thirty different ways if you have enough footage, but that doesn’t mean it’s the right way to play the scene. The one thing that the old-timers spoke about most often was their pride in being able to make films quickly and economically.

I shoot very tight, and because of that editing goes very quickly. We showed What’s Up, Doc? to the studio three weeks after we wrapped. It was the same thing with Paper Moon and Daisy Miller. “Protection” is a dirty word. I think running around covering things from every angle can ruin the morale on a set, particularly when you have a big, complicated setup and everybody has to work like a sonofabitch to get it right. Maybe it’s a whole scene without a cut, like the shots we did in Daisy Miller which were fifteen pages without a cut, five minutes. You work at it for days and then you get it and everybody cheers, and then you say, “Now, we need a little protection here in case it doesn’t work.” Well, they’ll kill you.

With scenes where you have to do several takes to get it right, do the performances ever change?

In movies something happens and it only happens once. That’s the difference between movie acting and stage acting. There are very few moments in my pictures that I can say are perfect, but if there are any, it’s little things, like a look between two people or a line. It’s nothing I could ever have planned, and usually happens in a close-up. Almost everything I’m happiest with in the pictures I’ve done were first takes. There’s always a bit of luck in any shot. You’re hoping that something will go wrong that will make it great, a lucky accident of sorts. John Ford said that he thinks the best things in pictures happen by accident. Orson Welles said to me, “A director is essentially a man who presides over accidents.” What you’re really trying to do when you direct a picture is create an atmosphere in which accidents will happen. Things will go a little bit wrong and you’ll say, “That’s great. That’s the one.” Who knows why it’s the one? Something was going through the actor’s mind, or a cloud moved in at a certain point. Henry Fonda told me this story about Ford directing Mister Roberts. He said, “We were shooting a scene with William Powell. He was kind of shaky and nervous. It was a long scene, about four or five pages, and Ford set up the camera, and we started to roll—it was outside on a ship—and Jesus, Bill was just terrible. His hands were shaking and he could barely remember his lines. I was thinking, ‘When is he going to cut?’ But I went on playing the scene and we went on and on, and the scene was over and Ford said, ‘Cut! Print! Did you see that cloud move in there? Jesus, wasn’t that a hell of a thing? What a hell of a shot that was!’”

You said that the time to make up your mind about what the scene is about is when you’re shooting it. But aren’t some of those decisions also to be made in the script?

No. I don’t like scripts to overly define the mechanics of the film. You might indicate certain things that jump out at you, like a close-up or an establishing shot, but I don’t make decisions as to where the camera is going to be until the last moment. It’s important to keep yourself fresh and open to ideas, like the actor suggesting something. But basically I know what the scene is about and how many angles I need to cover it. If you have a scene that plays well in a single shot, then just leave it alone. Maybe shoot four or five takes, but forget about coverage. Ford told me about a scene with two actors he held for a long time, and he said, “Well, you can see their faces and hear what they’re saying. No reason to cut.” I asked Orson how he would define the difference between shooting a scene in one shot or cutting it up into many pieces. He said, “That was what we used to say separated the men from the boys.” Joseph H. Lewis was shooting a bank robbery and got it only with a single camera from inside the car. I asked him about this entire ten-minute shot. Did he get any coverage? He said, “No, a man must have courage.”

Can you say anything about casting?

I once asked Hitchcock about the difference between casting an unknown actor and a star in a picture. He said, “You’re driving along the street and there’s an accident up ahead. You slow up as you go by the accident and see somebody. You don’t know who it is and you say, ‘Oh, tsk, tsk. Too bad,’ and you drive on. Now,” he said, “the same scene. You’re driving along, you look to see who it is and, my god, it’s your brother. That’s the difference between casting an unknown and Cary Grant.” You know and care about Cary Grant. You don’t have to set it up. He just walks on the screen. That instant familiarity is what you are paying him for.

Have you ever run into any problems with actors?

I think you have to be some kind of actor to be a good director, because essentially you have to hear the words in your mind. It’s like how a conductor hears a score. He doesn’t necessarily need to have the musicians there to know how it ought to sound. In fact, what he’s trying to do is get all the musicians to sound like what he hears. When I’m working on a script I hear it a certain way, and then it’s a question of getting the actors to sound the same way. Sometimes they do something interesting that’s different and I say, “Hey, I like that. That’s nice. Keep that.” But generally speaking you’re trying to get them to do it more or less the way you’re hearing it. Of course there are a million ways to do that. In fact, there are as many ways to do that as there are actors, because every actor is different. You beat Tatum O’Neal on the head or scare her, you indulge Burt Reynolds because he’s nervous, but essentially I show them what I want by either saying the line the way I think they ought to say it or getting up and acting it out. I don’t do it out of any kind of particularly egotistical desire to be a ham, but because I don’t know how else to describe it.

Some actors are threatened by this, and if they don’t like it then I don’t do it. Usually it isn’t a problem. Some directors did all the time. Lubitsch, for example, acted out every role: the maids, the butlers, every role. I asked Jack Benny once—he was the only actor I ever met who’d worked with Lubitsch—“Did he act out all the parts?” “Yeah, all the parts. It was a little broad but you got the idea.” That’s the thing: you got the idea. I got encouragement with this method of directing from James Cagney. I asked him at a dinner party, “What’s a good director to you?” He said, “Kid, I’ve only worked with five.” I said, “How many directors have you worked with in your life?” “Eighty-five. But only five are really directors.” So I said, “What does a real director do?” He said, “A director to me is a man who, if I don’t know what the hell to do, can get up and show me.”

Is it easier to do six less expensive pictures than one expensive one?

Making an expensive film is the worst thing in the world. When I was sort of a half-assed critic I wrote once about My Fair Lady and said that George Cukor had made a very good picture considering the limitations of $15 million. I found when I had $6 or $9 million, which I had on two pictures, that I was right. It’s a hell of a limitation. Things gets bigger and bigger and finally you’ve got all these people who don’t do anything, and you’re carrying them around with you. It’s like a goddamned army. You can’t just say, “Let’s not shoot this today. Let’s go over there.” It’s like saying, “We’re not going to invade at Normandy. We’re going to invade the Sea of Japan.” Somehow the freedom goes, and at the same time so does the fun.

I’ve always thought that making a film is fun only when you feel that what you’re doing is sort of a crime. What you’re saying is, “Nobody knows what we’re really doing.” Jean Renoir once said that when you’re making a picture you should have conspirators around you, as opposed to associates. That’s why I love shooting at night. It’s the best time to shoot because everybody else is asleep and you’re really doing this terrible thing—you’re making this movie—and nobody knows what you’re doing. You’ve got to maintain that larcenous quality to your work as a director, and that’s what’s the matter with making big pictures.

What has it been like working with László Kovács as your cinematographer?

László had shot a bunch of nudie pictures before he did Targets and he’d never done what he thought was a good picture. In fact, his name on those had been Leslie Kovacs. His real name was László and he changed his name to fit more with an American image. I said, “Why in hell are you calling yourself Leslie? László Kovács is a beautiful name. It’s classical.” He said, “Okay, on this picture I’m going to put László. It’s the first picture I’m proud of.”

Otto Preminger once said to me that there were two kinds of good cameramen. “There’s the good cameraman who’ll give you what you want but doesn’t know why you want it, and there’s the other kind who can give you what you want and knows why you want it. Of course, it’s much more fun to work with the second type.” László’s the second type. I remember one shot we had on Paper Moon, in the café scene when Tatum says, “I want my $200.” The last setup in that sequence is a face-off between the two of them and the waitress comes up and says, “Hi there, precious.” He says, “Her name ain’t Precious.” We ended up shooting with a slightly low angle, which is exactly what I had in mind but didn’t know how to explain it to László. I just said, “Look, here’s what I want. It’s the last shot in the sequence and I want to get a kind of feeling like a Mexican standoff.” He said, “What’s that?” I said, “Give the impression of these two people opposing each other but we don’t know which way it’s going to go.” He said, “Well, maybe if we shoot low,” and I said, “That’s good.”