One of the world’s greatest cinematic artists was Stanley Kubrick. A filmmaker both in control of the craft, Kubrick began his career (while still only a teenager) as a still photographer. He was born in Brooklyn, New York, and as a young man in between photo gigs he would earn money by hustling chess in the park. Kubrick was a master chess player and a master photographer, both without any formal training. The compositions of photography and the exact precession and decisive action it took to play chess would feature in all of his cinematic work as a marriage made in movie heaven.

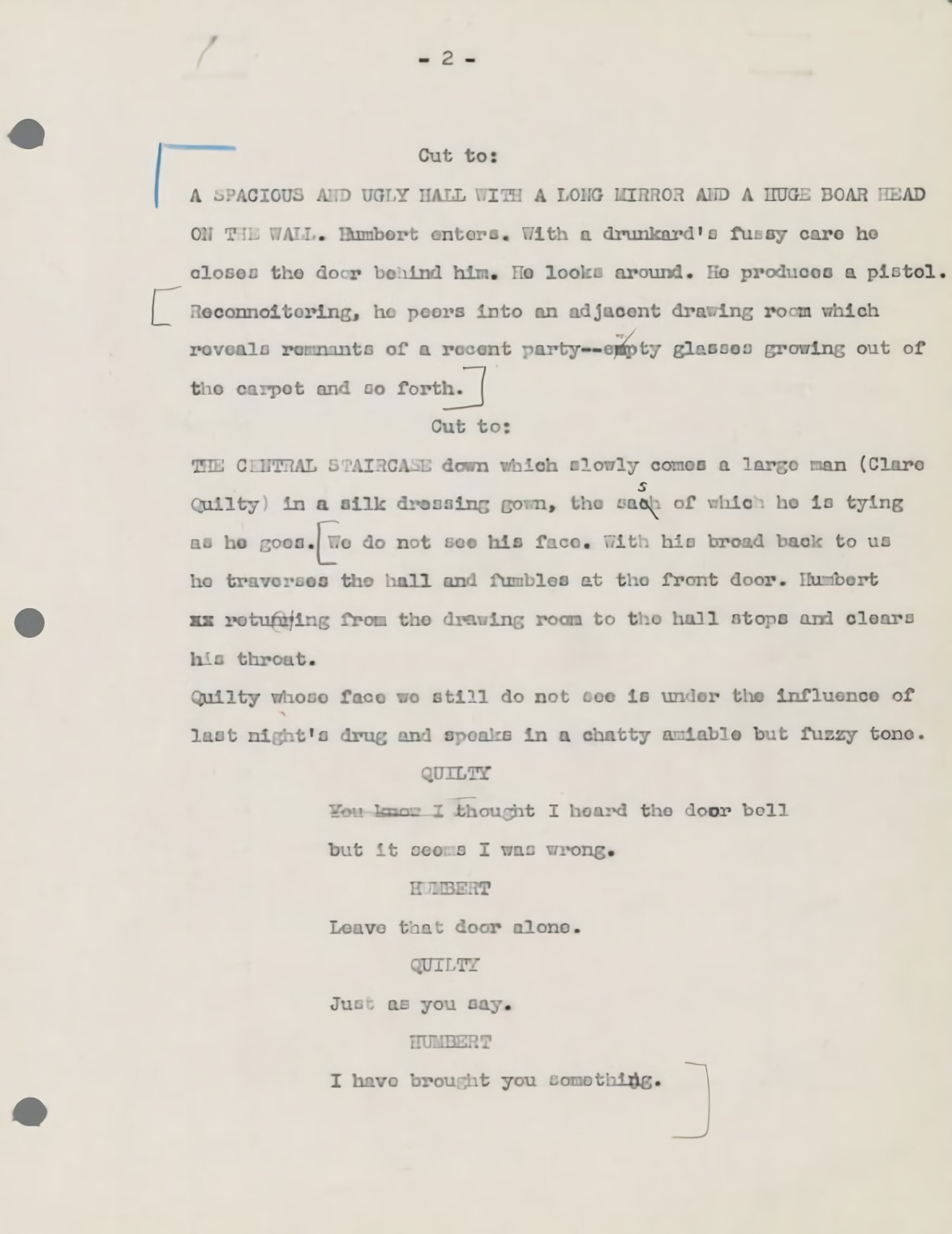

After the disappointing box office failure of the beautiful Barry Lyndon, Stanley Kubrick set his sights on a commercial property. He chose the proven genre of “horror” and when he came across the manuscript of Stephen King’s novel, The Shining, he found the kernel to spark his imagination. Along with horror novelist Diane Johnson, Kubrick crafted a screenplay that was more Jungian in tone dealing with the “shadow side” of man rather than the novel’s overt supernatural flavor.

Production began in May, 1978 at Elstree Studios in England. Scheduled to last seventeen weeks, it went fourteen months over and an estimated two hundred shooting days. Perhaps it was the failure of Lyndon to find an audience or his own inner competition, but Kubrick would stop at nothing to achieve what he called “the magic” to a given scene. Even if it required eighty-plus takes and hours if not days of rehearsal for one scene, one beat, or… one line. Kubrick was a competitive artist. But on this picture he was competing with himself and nothing would stop him.

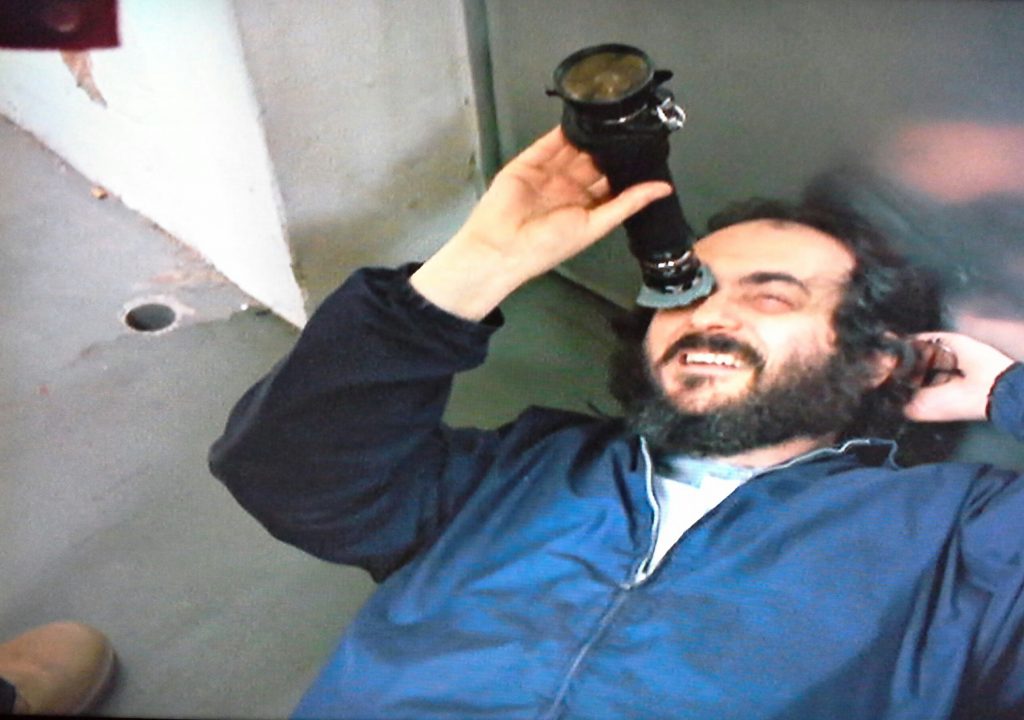

One shot in The Shining is a standout for two reasons. One, the composition is perfect in revealing the inner workings of the character it’s focused on, and two, it was conceived and executed in a matter of hours. This is an anomaly to be sure on a Stanley Kubrick shoot.

It is the low angle of Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson) locked in the Overlook Hotel dry goods pantry talking to his wife Wendy (Shelley Duvall) after she knocked him out with a baseball bat and locked him inside. Jack starts out trying to manipulate his distraught wife, then in a flash becomes maniacal and crazed with demonic childlike glee when he tells her that he has disabled the snow cat, Wendy and their young son Danny’s (portrayed by Danny Lloyd) only way to escape the haunted hotel.

The Overlook kitchen set was in fact not a set at all but a real kitchen at the studio that was used by the art department to paint all the Overlook Hotel’s maze-like carpet patterns. Yes, all the carpet in The Shining was “hand painted.” Kubrick and crew decided to use this as the kitchen set, which gave the production some sound issues due to the fact that it was not a set.

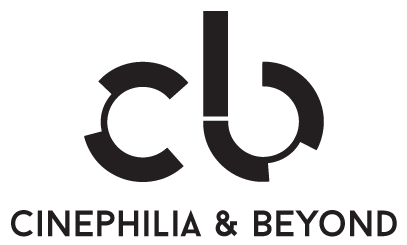

Kubrick began to block the scene as he always does with his director’s finder. Now, the fact that he blocked the scene with Jack Nicholson is something only Stanley Kubrick could get away with. No star would stand around and wait while the director comes up with the shot, that’s what stand-ins are for. But Kubrick was Kubrick and Jack knew this.

Within a matter of minutes Kubrick sparked to the idea of laying down on the floor of the pantry looking up to Jack as he leans on the door taunting his wife. At first Nicholson played the scene looking straight ahead. Then Kubrick suggested, “could you play it looking down as you say the lines?” Jack did, and Kubrick began to smile like a child playing with the greatest train set in the world as he looked through the finder. He found the perfect shot for the scene.

Within an hour Kubrick had his camera crew, focus puller Doug Milsome and camera operator Kelvin Pike who had a small fill light taped to his chest, on the floor between Jack Nicholson’s legs to film this now iconic image. Kubrick lay next to Pike to watch the performance and to put his hand over the fill light as diffusion.

To this end, Kubrick retained his autodidactic filmmaking craft that he learned on the streets of New York City. Only a handful of takes were shot and in less than an hour Kubrick and crew created an image that is memorable and one that seems to enter into the fractured state of mind Jack was in during that scene, and more importantly it brings the audience into that state of mind.

As Kubrick would say, “real is good, but interesting is better.”

Will McCrabb is a writer in the city of broken dreams