What is now considered one of Stanley Kubrick’s most accomplished films, as well as an example of innovative, audacious filmmaking at its best, was almost given birth to by accident. After Kubrick’s dream of making Napoleon crumbled into pieces, he used this studious research and shifted his ambitions and talent into William Makepeace Thackeray’s 1844 novel The Luck of Barry Lyndon. The story of an unscrupulous Irish scoundrel who marries into high society and advances in the aristocratic society of 18th century England proved an ideal ground for the master to exhibit his storytelling powers. With the significant help of his director of photography John Alcott, Kubrick created a cinematic world that could be most easily described as a moving 18th century painting. Giving its best to avoid using electric sources of artificial light, relying on the illuminating power of candles and natural lighting, investing enormous effort into costume design, Barry Lyndon looks genuine through and through. Moreover, it leaves the impression of actually being comprised of works of art taken down from the walls of some filthily rich British nobleman. The colors, shading and atmosphere aren’t the only things Barry Lyndon has in common with two-dimensional works of art—the film also appropriates a certain quality of unresponsiveness. It’s somehow distanced from the viewers, it masterfully puts them into the position of an observer in an art gallery, not someone who actively interacts with the screen. Barry Lyndon is detached, cold and to a degree unburdened with the pressure of entertaining an audience. Kubrick, who not only directed but also adapted Thackeray’s satiric novel to produce a sharp, narration-driven script, created a technically breath-taking, arrogantly and recklessly fearless, monumental film over three hours long. The first reactions to it, unfortunately for Kubrick’s peace of mind, perhaps failed to be as enthusiastic as the piece deserved, but decades that followed certainly did Barry justice. All hail Barry Lyndon, an exceptional piece of filmmaking, a masterclass in bringing a unique filmmaker’s vision to life, a work of art only a few others have the quality to measure up to.

I’m not sure if I can say that I have a favourite Kubrick picture, but somehow I keep coming back to Barry Lyndon. I think that’s because it’s such a profoundly emotional experience. The emotion is conveyed through the movement of the camera, the slowness of the pace, the way the characters move in relation to their surroundings. People didn’t get it when it came out. Many still don’t. Basically, in one exquisitely beautiful image after another, you’re watching the progress of a man as he moves from the purest innocence to the coldest sophistication, ending in absolute bitterness—and it’s all a matter of simple, elemental survival. It’s a terrifying film because all the candlelit beauty is nothing but a veil over the worst cruelty. But it’s real cruelty, the kind you see every day in polite society. —Martin Scorsese

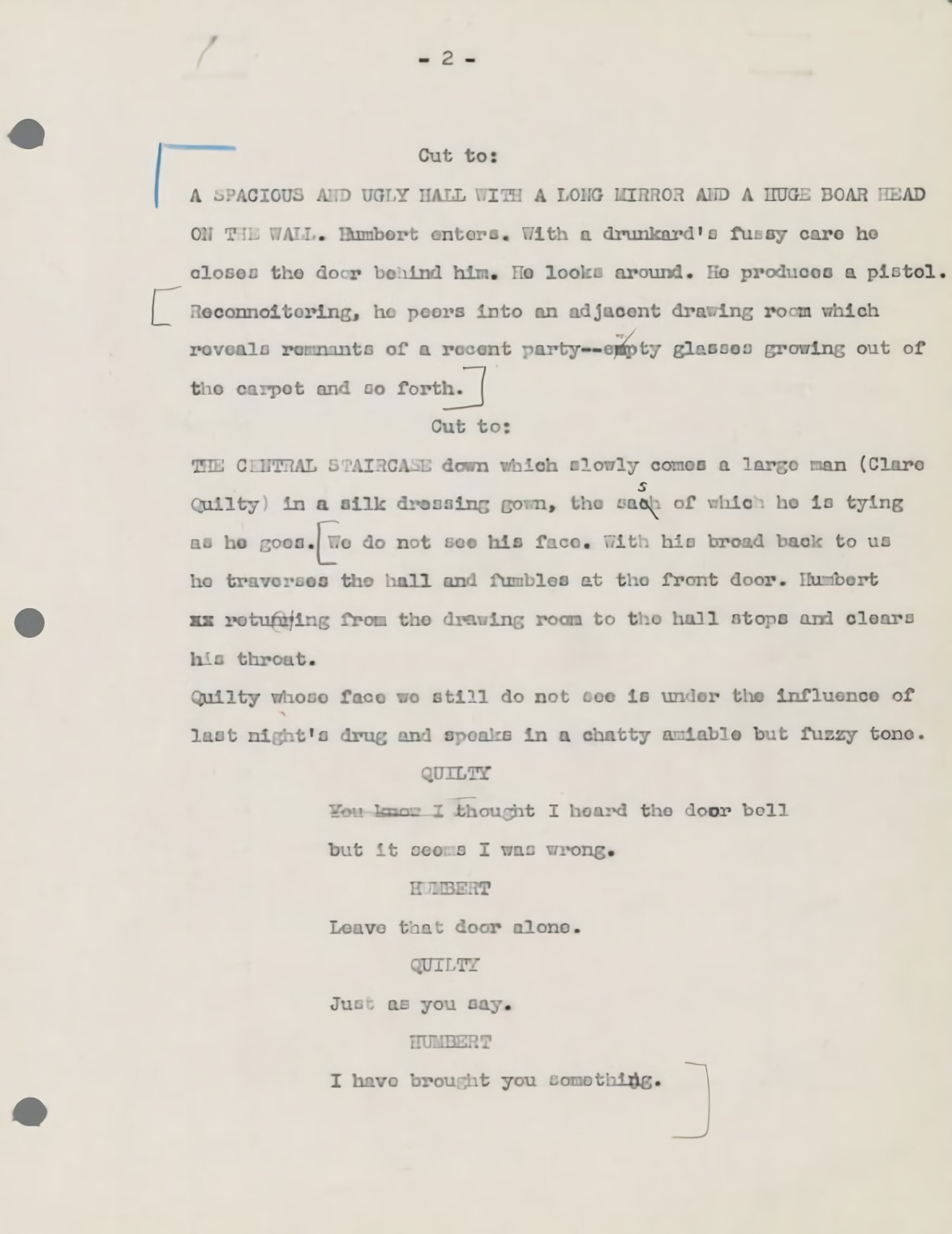

What we have here is an extremely rare document of exceptional historical value; a monumentally important screenplay. Dear every screenwriter/filmmaker, read Stanley Kubrick’s screenplay for Barry Lyndon [PDF]. (NOTE: For educational and research purposes only). The DVD/Blu-ray of the film is available from the Criterion Collection and other online retailers. Absolutely our highest recommendation.

Loading...

Loading...

KUBRICK’S GILDED AGE

by Pauline Kael

“This film is a masterpiece in every insignificant detail. Kubrick isn’t taking pictures in order to make movies, he’s making movies in order to take pictures. Barry Lyndon indicates that Kubrick is thinking through his camera, and that’s not really how good movies get made—though it’s what gives them their dynamism, if a director puts the images together vivifyingly. for an emotional impact. I wish Stanley Kubrick would come home to this country to make movies again, working fast on modern subjects—maybe even doing something tacky, for the hell of it. There was more film art in his early The Killing than there is in Barry Lyndon, and you didn’t feel older when you came out of it. Orwell also said of Thackeray that his characteristic flavor is ‘the flavor of burlesque, of a world where no one is good and nothing is serious.’ For Kubrick, everything has become serious. The way he’s been working, in self-willed isolation, with each film consuming years of anxiety, there’s no ground between masterpiece and failure. And the pressure shows. There must be some reason that, in a film dealing with a licentious man in a licentious time, the only carnality—indeed, the only strong emotion—is in Barry’s brutally caning his stepson. When a director gets to the point where the one emotion he shows is morally and physically ugly, maybe he ought to knock off on the big, inviolable endeavors.” —Kubrick’s Gilded Age, by Pauline Kael

KUBRICK ON ‘BARRY LYNDON’

The following interview with Stanley Kubrick is excerpted from the book ‘Kubrick’ by Michel Ciment. It was conducted upon the release of Barry Lyndon in 1975 and published in a partial form at the time. In 1981 Stanley Kubrick revised and approved the complete text of the interview for the English edition of Ciment’s book on his films.

You have given almost no interviews on Barry Lyndon. Does this decision relate to this film particularly, or is it because you are reluctant to speak about your work?

I suppose my excuse is that the picture was ready only a few weeks before it opened and I really had no time to do any interviews. But if I’m to be completely honest, it’s probably due more to the fact that I don’t like doing interviews. There is always the problem of being misquoted or, what’s even worse, of being quoted exactly, and having to see what you’ve said in print. Then there are the mandatory—“How did you get along with actor X, Y or Z?”—“Who really thought of good idea A, B or C?” I think Nabokov may have had the right approach to interviews. He would only agree to write down the answers and then send them on to the interviewer who would then write the questions.Do you feel that Barry Lyndon is a more secret film, more difficult to talk about?

Not really. I’ve always found it difficult to talk about any of my films. What I generally manage to do is to discuss the background information connected with the story, or perhaps some of the interesting facts which might be associated with it. This approach often allows me to avoid the “What does it mean? Why did you do it?” questions. For example, with Dr. Strangelove I could talk about the spectrum of bizarre ideas connected with the possibilities of accidental or unintentional warfare. 2001: A Space Odyssey allowed speculation about ultra-intelligent computers, life in the universe, and a whole range of science-fiction ideas. A Clockwork Orange involved law and order, criminal violence, authority versus freedom, etc. With Barry Lyndon you haven’t got these topical issues to talk around, so I suppose that does make it a bit more difficult.Your last three films were set in the future. What led you to make an historical film?

I can’t honestly say what led me to make any of my films. The best I can do is to say I just fell in love with the stories. Going beyond that is a bit like trying to explain why you fell in love with your wife: she’s intelligent, has brown eyes, a good figure. Have you really said anything? Since I am currently going through the process of trying to decide what film to make next, I realize just how uncontrollable is the business of finding a story, and how much it depends on chance and spontaneous reaction. You can say a lot of “architectural” things about what a film story should have: a strong plot, interesting characters, possibilities for cinematic development, good opportunities for the actors to display emotion, and the presentation of its thematic ideas truthfully and intelligently. But, of course, that still doesn’t really explain why you finally chose something, nor does it lead you to a story. You can only say that you probably wouldn’t choose a story that doesn’t have most of those qualities.Since you are completely free in your choice of story material, how did you come to pick up a book by Thackeray, almost forgotten and hardly republished since the nineteenth century?

I have had a complete set of Thackeray sitting on my bookshelf at home for years, and I had to read several of his novels before reading Barry Lyndon. At one time, Vanity Fair interested me as a possible film but, in the end, I decided the story could not be successfully compressed into the relatively short time-span of a feature film. This problem of length, by the way, is now wonderfully accommodated for by the television miniseries which, with its ten-to twelve-hour length, pressed on consecutive nights, has created a completely different dramatic form. Anyway, as soon as I read Barry Lyndon I became very excited about it. I loved the story and the characters, and it seemed possible to make the transition from novel to film without destroying it in the process. It also offered the opportunity to do one of the things that movies can do better than any other art form, and that is to present historical subject matter. Description is not one of the things that novels do best but it is something that movies do effortlessly, at least with respect to the effort required of the audience. This is equally true for science-fiction and fantasy, which offer visual challenges and possibilities you don’t find in contemporary stories.

How did you come to adopt a third-person commentary instead of the first-person narrative which is found in the book?

I believe Thackeray used Redmond Barry to tell his own story in a deliberately distorted way because it made it more interesting. Instead of the omniscient author, Thackeray used the imperfect observer, or perhaps it would be more accurate to say the dishonest observer, thus allowing the reader to judge for himself, with little difficulty, the probable truth in Redmond Barry’s view of his life. This technique worked extremely well in the novel but, of course, in a film you have objective reality in front of you all of the time, so the effect of Thackeray’s first-person story-teller could not be repeated on the screen. It might have worked as comedy by the juxtaposition of Barry’s version of the truth with the reality on the screen, but I don’t think that Barry Lyndon should have been done as a comedy.You didn’t think of having no commentary?

There is too much story to tell. A voice-over spares you the cumbersome business of telling the necessary facts of the story through expositional dialogue scenes which can become very tiresome and frequently unconvincing: “Curse the blasted storm that’s wrecked our blessed ship!” Voice-over, on the other hand, is a perfectly legitimate and economical way of conveying story information which does not need dramatic weight and which would otherwise be too bulky to dramatize.But you use it in other way—to cool down the emotion of a scene, and to anticipate the story. For instance, just after the meeting with the German peasant girl—a very moving scene—the voice-over compares her to a town having been often conquered by siege.

In the scene that you’re referring to, the voice-over works as an ironic counterpoint to what you see portrayed by the actors on the screen. This is only a minor sequence in the story and has to be presented with economy. Barry is tender and romantic with the girl but all he really wants is to get her into bed. The girl is lonely and Barry is attractive and attentive. If you think about it, it isn’t likely that he is the only soldier she has brought home while her husband has been away to the wars. You could have had Barry give signals to the audience, through his performance, indicating that he is really insincere and opportunistic, but this would be unreal. When we try to deceive we are as convincing as we can be, aren’t we? The film’s commentary also serves another purpose, but this time in much the same manner it did in the novel. The story has many twists and turns, and Thackeray uses Barry to give you hints in advance of most of the important plot developments, thus lessening the risk of their seeming contrived.When he is going to meet the Chevalier Balibari, the commentary anticipates the emotions we are about to see, thus possibly lessening their effect.

Barry Lyndon is a story which does not depend upon surprise. What is important is not what is going to happen, but how it will happen. I think Thackeray trades off the advantage of surprise to gain a greater sense of inevitability and a better integration of what might otherwise seem melodramatic or contrived. In the scene you refer to where Barry meets the Chevalier, the film’s voice-over establishes the necessary groundwork for the important new relationship which is rapidly to develop between the two men. By talking about Barry’s loneliness being so far from home, his sense of isolation as an exile, and his joy at meeting a fellow countryman in a foreign land, the commentary prepares the way for the scenes which are quickly to follow showing his close attachment to the Chevalier. Another place in the story where I think this technique works particularly well is where we are told that Barry’s young son, Bryan, is going to die at the same time we watch the two of them playing happily together. In this case, I think the commentary creates the same dramatic effect as, for example, the knowledge that the Titanic is doomed while you watch the carefree scenes of preparation and departure. These early scenes would be inexplicably dull if you didn’t know about the ship’s appointment with the iceberg. Being told in advance of the impending disaster gives away surprise but creates suspense.

There is very little introspection in the film. Barry is open about his feelings at the beginning of the film, but then he becomes less so.

At the beginning of the story, Barry has more people around him to whom he can express his feelings. As the story progresses, and particularly after his marriage, he becomes more and more isolated. There is finally no one who loves him, or with whom he can talk freely, with the possible exception of his young son, who is too uoung to be of much help. At the same time I don’t think that the lack of introspective dialogue scenes are any loss to the story. Barry’s feelings are there to be seen as he reacts to the increasingly difficult circumstances of his life. I think this is equally true for the other characters in the story. In any event, scenes of people talking about themselves are often very dull.In contrast to films which are preoccupied with analyzing the psychology of the characters, yours tend to maintain a mystery around them. Reverend Runt, for instance, is a very opaque person. You don’t know exactly what his motivations are.

But you know a lot about Reverend Runt, certainly all that is necessary. He dislikes Barry. He is secretly in love with Lady Lyndon, in his own prim, repressed, little way. His little smile of triumph, in the scene in the coach, near the end of the film, tells you all you need to know regarding the way he feels about Barry’s misfortune, and the way things have worked out. You certainly don’t have the time in a film to develop the motivations of minor characters.Lady Lyndon is even more opaque.

Thackeray doesn’t tell you a great deal about her in the novel. I found that very strange. He doesn’t give you a lot to go on. There are, in fact, very few dialogue scenes with her in the book. Perhaps he meant her to be something of a mystery. But the film gives you a sufficient understanding of her anyway.You made important changes in your adaptation, such as the invention of the last duel, and the ending itself.

Yes, I did, but I was satisfied that they were consistent with the spirit of the novel and brought the story to about the same place the novel did, but in less time. In the book, Barry is pensioned off by Lady Lyndon. Lord Bullingdon, having been believed dead, returns from America. He finds Barry and gives him a beating. Barry, tended by his mother, subsequently dies in prison, a drunk. This, and everything that went along with it in the novel to make it credible would have taken too much time on the screen. In the film, Bullingdon gets his revenge and Barry is totally defeated, destined, one can assume, for a fate not unlike that which awaited him in the novel.And the scene of the two homosexuals in the lake was not in the book either.

The problem here was how to get Barry out of the British Army. The section of the book dealing with this is also fairly lengthy and complicated. The function of the scene between the two gay officers was to provide a simpler way for Barry to escape. Again, it leads to the same end result as the novel but by a different route. Barry steals the papers and uniform of a British officer which allow him to make his way to freedom. Since the scene is purely expositional, the comic situation helps to mask your intentions.

Were you aware of the multiple echoes that are found in the film: flogging in the army, flogging at home, the duels, etc., and the narrative structure resembling that of A Clockwork Orange? Does this geometrical pattern attract you?

The narrative symmetry arose primarily out of the needs of telling the story rather than as part of a conscious design. The artistic process you go through in making a film is as much a matter of discovery as it is the execution of a plan. Your first responsibility in writing a screenplay is to pay the closest possible attention to the author’s ideas and make sure you really understand what he has written and why he has written it. I know this sounds pretty obvious but you’d be surprised how often this is not done. There is a tendency for the screenplay writer to be “creative” too quickly. The next thing is to make sure that the story survives the selection and compression which has to occur in order to tell it in a maximum of three hours, and preferably two. This phase usually seals the fate of most major novels, which really need the large canvas upon which they are presented.In the first part of A Clockwork Orange, we were against Alex. In the second part, we were on his side. In this film, the attraction/repulsion feeling towards Barry is present throughout.

Thackeray referred to it as “a novel without a hero.” Barry is naive and uneducated. He is driven by a relentless ambition for wealth and social position. This proves to be an unfortunate combination of qualities which eventually lead to great misfortune and unhappiness for himself and those around him. Your feelings about Barry are mixed but he has charm and courage, and it is impossible not to like him despite his vanity, his insensitivity and his weaknesses. He is a very real character who is neither a conventional hero nor a conventional villain.The feeling that we have at the end is one of utter waste.

Perhaps more a sense of tragedy, and because of this the story can assimilate the twists and turns of the plot without becoming melodrama. Melodrama uses all the problems of the world, and the difficulties and disasters which befall the characters, to demonstrate that the world is, after all, a benevolent and just place.The last sentence which says that all the characters are now equal can be taken as a nihilistic or religious statement. From your films, one has the feeling that you are a nihilist who would like to believe.

I think you’ll find that it is merely an ironic postscript taken from the novel. Its meaning seems quite clear to me and, as far as I’m concerned, it has nothing to do with nihilism or religion.One has the feeling in your films that the world is in a constant state of war. The apes are fighting in 2001. There is fighting, too, in Paths Of Glory, and Dr. Strangelove. In Barry Lyndon, you have a war in the first part, and then in the second part we find the home is a battleground, too.

Drama is conflict, and violent conflict does not find its exclusive domain in my films. Nor is it uncommon for a film to be built around a situation where violent conflict is the driving force. With respect to Barry Lyndon, after his successful struggle to achieve wealth and social position, Barry proves to be badly unsuited to this role. He has clawed his way into a gilded cage, and once inside his life goes really bad. The violent conflicts which subsequently arise come inevitably as a result of the characters and their relationships. Barry’s early conflicts carry him forth into life and they bring him adventure and happiness, but those in later life lead only to pain and eventually to tragedy.

In many ways, the film reminds us of silent movies. I am thinking particularly of the seduction of Lady Lyndon by Barry at the gambling table.

That’s good. I think that silent films got a lot more things right than talkies. Barry and Lady Lyndon sit at the gaming table and exchange lingering looks. They do not say a word. Lady Lyndon goes out on the balcony for some air. Barry follows her outside. They gaze longingly into each other’s eyes and kiss. Still not a word is spoken. It’s very romantic, but at the same time, I think it suggests the empty attraction they have for each other that is to disappear as quickly as it arose. It sets the stage for everything that is to follow in their relationship. The actors, the images and the Schubert worked well together, I think.Did you have Schubert’s Trio in mind while preparing and shooting this particular scene?

No, I decided on it while we were editing. Initially, I thought it was right to use only eighteenth-century music. But sometimes you can make ground-rules for yourself which prove unnecessary and counter-productive. I think I must have listened to every LP you can buy of eighteenth-century music. One of the problems which soon became apparent is that there are no tragic love-themes in eighteenth-century music. So eventually I decided to use Schubert’s Trio in E Flat, Opus 100, written in 1828. It’s a magnificent piece of music and it has just the right restrained balance between the tragic and the romantic without getting into the headier stuff of later Romanticism.You also cheated in another way by having Leonard Rosenman orchestrate Handel’s Sarabande in a more dramatic style than you would find in eighteenth-century composition.

This arose from another problem about eighteenth-century music—it isn’t very dramatic, either. I first came across the Handel theme played on a guitar and, strangely enough, it made me think of Ennio Morricone. I think it worked very well in the film, and the very simple orchestration kept it from sounding out of place.It also accompanies the last duel—not present in the novel—which is one of the most striking scenes in the film and is set in a dovecote.

The setting was a tithe barn which also happened to have a lot of pigeons resting in the rafters. We’ve seen many duels before in films, and I wanted to find a different and interesting way to present the scene. The sound of the pigeons added something to this, and, if it were a comedy, we could have had further evidence of the pigeons. Anyway, you tend to expect movie duels to be fought outdoors, possibly in a misty grove of trees at dawn. I thought the idea of placing the duel in a barn gave it an interesting difference. This idea came quite by accident when one of the location scouts returned with some photographs of the barn. I think it was Joyce who observed that accidents are the portals to discovery. Well, that’s certainly true in making films. And perhaps in much the same way, there is an aspect of film-making which can be compared to a sporting contest. You can start with a game plan but depending on where the ball bounces and where the other side happens to be, opportunities and problems arise which can only be effectively dealt with at that very moment.In 2001: A Space Odyssey, for example, there seemed no clever way for HAL to learn that the two astronauts distrusted him and were planning to disconnect his brain. It would have been irritatingly careless of them to talk aloud, knowing that HAL would hear and understand them. Then the perfect solution presented itself from the actual phsical layout of the space pod in the pod bay. The two men went into the pod and turned off every switch to make them safe from HAL’s microphones. They sat in the pod facing each other and in the center of the shot, visible through the sound-proof glass port, you could plainly see the red glow of HAL’s bug-eye lens, some fifteen feet away. What the conspirators didn’t think of was that HAL would be able to read their lips.

Did you find it more constricting, less free, making an historical film where we all have precise conceptions of a period? Was it more of a challenge?

No, because at least you know what everything looked like. In 2001: A Space Odyssey everything had to be designed. But neither type of film is easy to do. In historical and futuristic films, there is an inverse relationship between the ease the audience has taking in at a glance the sets, costumes and decor, and the film-maker’s problems in creating it. When everything you see has to be designed and constructed, you greatly increase the cost of the film, add tremendously to all the normal problems of film-making, making it virtually impossible to have the flexibility of last-minute changes which you can manage in a contemporary film.You are well-known for the thoroughness with which you accumulate information and do research when you work on a project. Is it for you the thrill of being a reporter or a detective?

I suppose you could say it is a bit like being a detective. On Barry Lyndon, I accumulated a very large picture file of drawings and paintings taken from art books. These pictures served as the reference for everything we needed to make—clothes, furniture, hand props, architecture, vehicles, etc. Unfortunately, the pictures would have been too awkward to use while they were still in the books, and I’m afraid we finally had very guiltily to tear up a lot of beautiful art books. They were all, fortunately, still in print which made it seem a little less sinful. Good research is an absolute necessity and I enjoy doing it. You have an important reason to study a subject in much greater depth than you would ever have done otherwise, and then you have the satisfaction of putting the knowledge to immediate good use. The designs for the clothes were all copied from drawings and paintings of the period. None of them were designed in the normal sense. This is the best way, in my opinion, to make historical costumes. It doesn’t seem sensible to have a designer interpret—say—the eighteenth century, using the same picture sources from which you could faithfully copy the clothes. Neither is there much point sketching the costumes again when they are already beautifully represented in the paintings and drawings of the period. What is very important is to get some actual clothes of the period to learn how they were originally made. To get them to look right, you really have to make them the same way. Consider also the problem of taste in designing clothes, even for today. Only a handful of designers seem to have a sense of what is striking and beautiful. How can a designer, however brilliant, have a feeling for the clothes of another period which is equal to that of the people and the designers of the period itself, as recorded in their pictures? I spent a year preparing Barry Lyndon before the shooting began and I think this time was very well spent. The starting point and sine qua non of any historical or futuristic story is to make you believe what you see.The danger in an historical film is that you lose yourself in details, and become decorative.

The danger connected with any multi-faceted problem is that you might pay too much attention to some of the problems to the detriment of others, but I am very conscious of this and I make sure I don’t do that.Why do you prefer natural lighting?

Because it’s the way we see things. I have always tried to light my films to simulate natural light; in the daytime using the windows actually to light the set, and in night scenes the practical lights you see in the set. This approach has its problems when you can use bright electric light sources, but when candelabras and oil lamps are the brightest light sources which can be in the set, the difficulties are vastly increased. Prior to Barry Lyndon, the problem has never been properly solved. Even if the director and cameraman had the desire to light with practical light sources, the film and the lenses were not fast enough to get an exposure. A 35mm movie camera shutter exposes at about 1/50 of a second, and a useable exposure was only possible with a lens at least 100% faster than any which had ever been used on a movie camera. Fortunately, I found just such a lens, one of a group of ten which Zeiss had specially manufactured for NASA satellite photography. The lens had a speed of fO.7, and it was 100% faster than the fastest movie lens. A lot of work still had to be done to it and to the camera to make it useable. For one thing, the rear element of the lens had to be 2.5mm away from the film plane, requiring special modification to the rotating camera shutter. But with this lens it was now possible to shoot in light conditions so dim that it was difficult to read. For the day interior scenes, we used either the real daylight from the windows, or simulated daylight by banking lights outside the windows and diffusing them with tracing paper taped on the glass. In addition to the very beautiful lighting you can achieve this way, it is also a very practical way to work. You don’t have to worry about shooting into your lighting equipment. All your lighting is outside the window behind tracing paper, and if you shoot towwards the window you get a very beautiful and realistic flare effect.

How did you decide on Ryan O’Neal?

He was the best actor for the part. He looked right and I was confident that he possessed much greater acting ability than he had been allowed to show in many of the films he had previously done. In retrospect, I think my confidence in him was fully justified by his performance, and I still can’t think of anyone who would have been better for the part. The personal qualities of an actor, as they relate to the role, are almost as important as his ability, and other actors, say, like Al Pacino, Jack Nicholson or Dustin Hoffman, just to name a few who are great actors, would nevertheless have been wrong to play Barry Lyndon. I liked Ryan and we got along very well together. In this regard the only difficulties I have ever had with actors happened when their acting technique wasn’t good enough to do something you asked of them. One way an actor deals with this difficulty is to invent a lot of excuses that have nothing to do with the real problem. This was very well represented in Truuffaut’s Day For Night when Valentina Cortese, the star of the film within the film, hadn’t bothered to learn her lines and claimed her dialogue fluffs were due to the confusion created by the script girl playing a bit part in the scene.How do you explain some of the misunderstandings about the film by the American press and the English press?

The American press was predominantly enthusiastic about the film, and Time magazine ran a cover story about it. The international press was even more enthusiastic. It is true that the English press was badly split. But from the very beginning, all of my films have divided the critics. Some have thought them wonderful, and others have found very little good to say. But subsequent critical opinion has always resulted in a very remarkable shift to the favorable. In one instance, the same critic who originally rapped the film has several years later put it on an all-time best list. But, of course, the lasting and ultimately most important reputation of a film is not based on reviews, but on what, if anything, people say about it over the years, and on how much affection for it they have.You are an innovator, but at the same time you are very conscious of tradition.

I try to be, anyway. I think that one of the problems with twentieth-century art is its preoccupation with subjectivity and originality at the expense of everything else. This has been especially true in painting and music. Though initially stimulating, this soon impeded the full development of any particular style, and rewarded uninteresting and sterile originality. At the same time, it is very sad to say, films have had the opposite problem—they have consistently tried to formalize and repeat success, and they have clung to a form and style introduced in their infancy. The sure thing is what everone wants, and originality is not a nice word in this context. This is true despite the repeated example that nothing is as dangerous as a sure thing.You have abandoned original film music in your last three films.

Exclude a pop music score from what I am about to say. However good our best film composers may be, they are not a Beethoven, a Mozart or a Brahms. Why use music which is less good when there is such a multitude of great orchestral music available from the past and from our own time? When you’re editing a film, it’s very helpful to be able to try out different pieces of music to see how they work with the scene. This is not at all an uncommon practice. Well, with a little more care and thought, these temporary music tracks can become the final score. When I had completed the editing of 2001: A Space Odyssey, I had laid in temporary music tracks for almost all of the music which was eventually used in the film. Then, in the normal way, I engaged the services of a distinguished film composer to write the score. Although he and I went over the picture very carefully, and he listened to these temporary tracks (Strauss, Ligeti, Khatchaturian) and agreed that they worked fine and would serve as a guide to the musical objectives of each sequence he, nevertheless, wrote and recorded a score which could not have been more alien to the music we had listened to, and much more serious than that, a score which, in my opinion, was completely inadequate for the film. With the premiere looming up, I had no time left even to think about another score being written, and had I not been able to use the music I had already selected for the temporary tracks I don’t know what I would have done. The composer’s agent phoned Robert O’Brien, the then head of MGM, to warn him that if I didn’t use his client’s score the film would not make its premiere date. But in that instance, as in all others, O’Brien trusted my judgment. He is a wonderful man, and one of the very few film bosses able to inspire genuine loyalty and affection from his film-makers.

Why did you choose to have only one flashback in the film: the child falling from the horse?

I didn’t want to spend the time which would have been required to show the entire story action of young Bryan sneaking away from the house, taking the horse, falling, being found, etc. Nor did I want to learn about the accident solely through the dialogue scene in which the farm workers, carrying the injured boy, tell Barry. Putting the flashback fragment in the middle of the dialogue scene seemed to be the right thing to do.Are your camera movements planned before?

Very rarely. I think there is virtually no point putting camera instructions into a screenplay, and only if some really important camera idea occurs to me, do I write it down. When you rehearse a scene, it is usually best not to think about the camera at all. If you do, I have found that it invariably interferes with the fullest exploration of the ideas of the scene. When, at last, something happens which you know is worth filming, that is the time to decide how to shoot it. It is almost but not quite true to say that when something really exciting and worthwhile is happening, it doesn’t matter how you shoot it. In any event, it never takes me long to decide on set-ups, lighting or camera movements. The visual part of film making has always come easiest to me, and that is why I am careful to subordinate it to the story and the performances.Do you like writing alone or would you like to work with a script writer?

I enjoy working with someone I find stimulating. One of the most fruitful and enjoyable collaborations I have had was with Arthur C. Clarke in writing the story of 2001: A Space Odyssey. One of the paradoxes of movie writing is that, with a few notable exceptions, writers who can really write are not interested in working on film scripts. They quite correctly regard their important work as being done for publication. I wrote the screenplay for Barry Lyndon alone. The first draft took three or four months but, as with all my films, the subsequent writing process never really stopped. What you have written and is yet unfilmed is inevitably affected by what has been filmed. New problems of content or dramatic weight reveal themselves. Rehearsing a scene can also cause script changes. However carefully you think about a scene, and however clearly you believe you have visualized it, it’s never the same when you finally see it played. Sometimes a totally new idea comes up out of the blue, during a rehearsal, or even during actual shooting, which is simply too good to ignore. This can necessitate the new scene being worked out with the actors right then and there. As long as the actors know the objectives of the scene, and understand their characters, this is less difficult and much quicker to do than you might imagine.

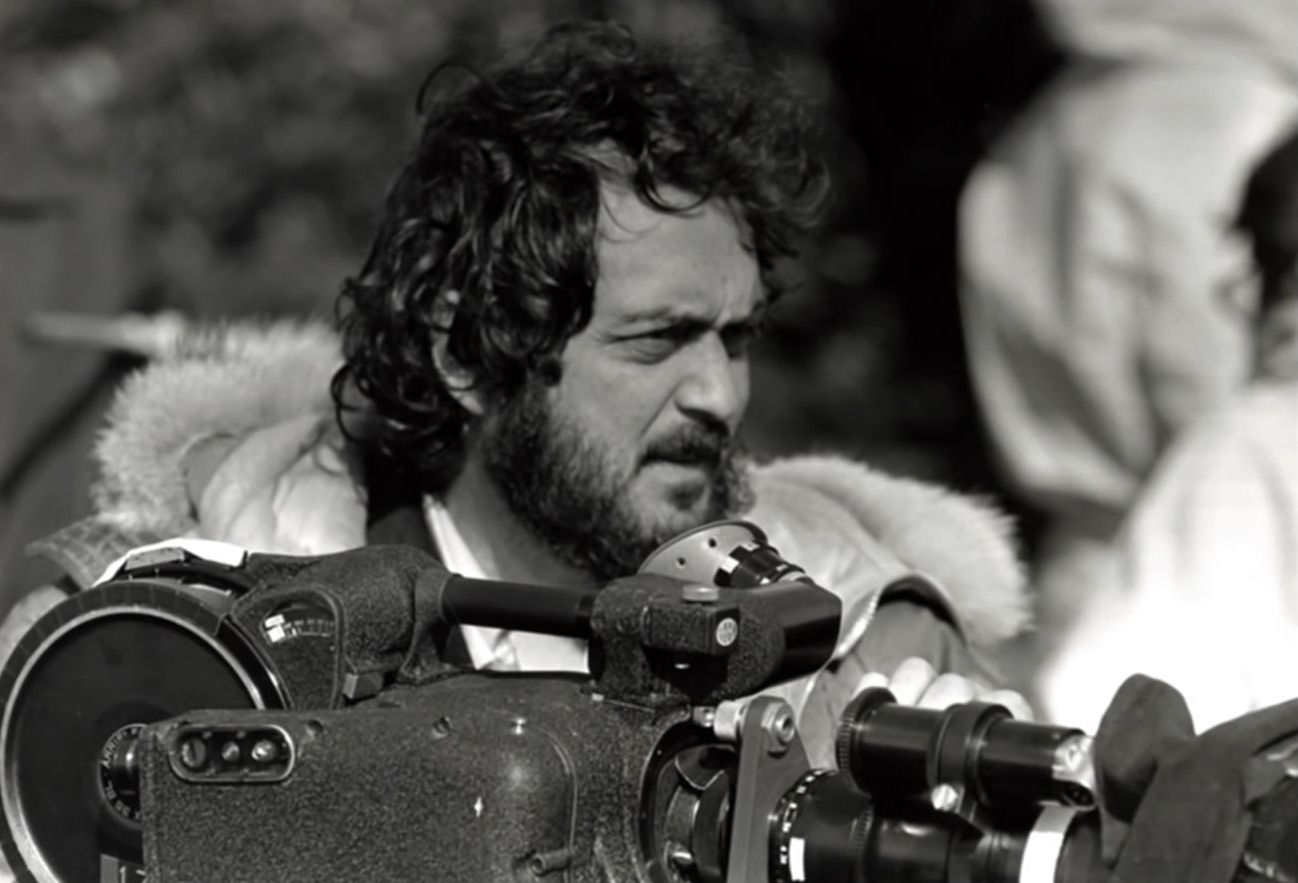

Below: Kubrick during a break in filming on one of the battlefield scenes on location in Ireland, with actor Ryan O’Neal. Kubrick’s teenage daughter Vivian is next to the director. Jan Harlan: “Stanley loved Barry Lyndon. He loved this upstart from nowhere, a conman, and he felt very strongly that Barry was representative of our society. What you see here is the normal sort of track they would lay down to move the camera—there was no Steadicam in those days. You had to be careful to point the camera in the right direction, otherwise you would film the track itself.” Still photographer: Keith Hamshere; SK Film Archives LLC, Warner Bros. and University of the Arts London. Courtesy of The Guardian.

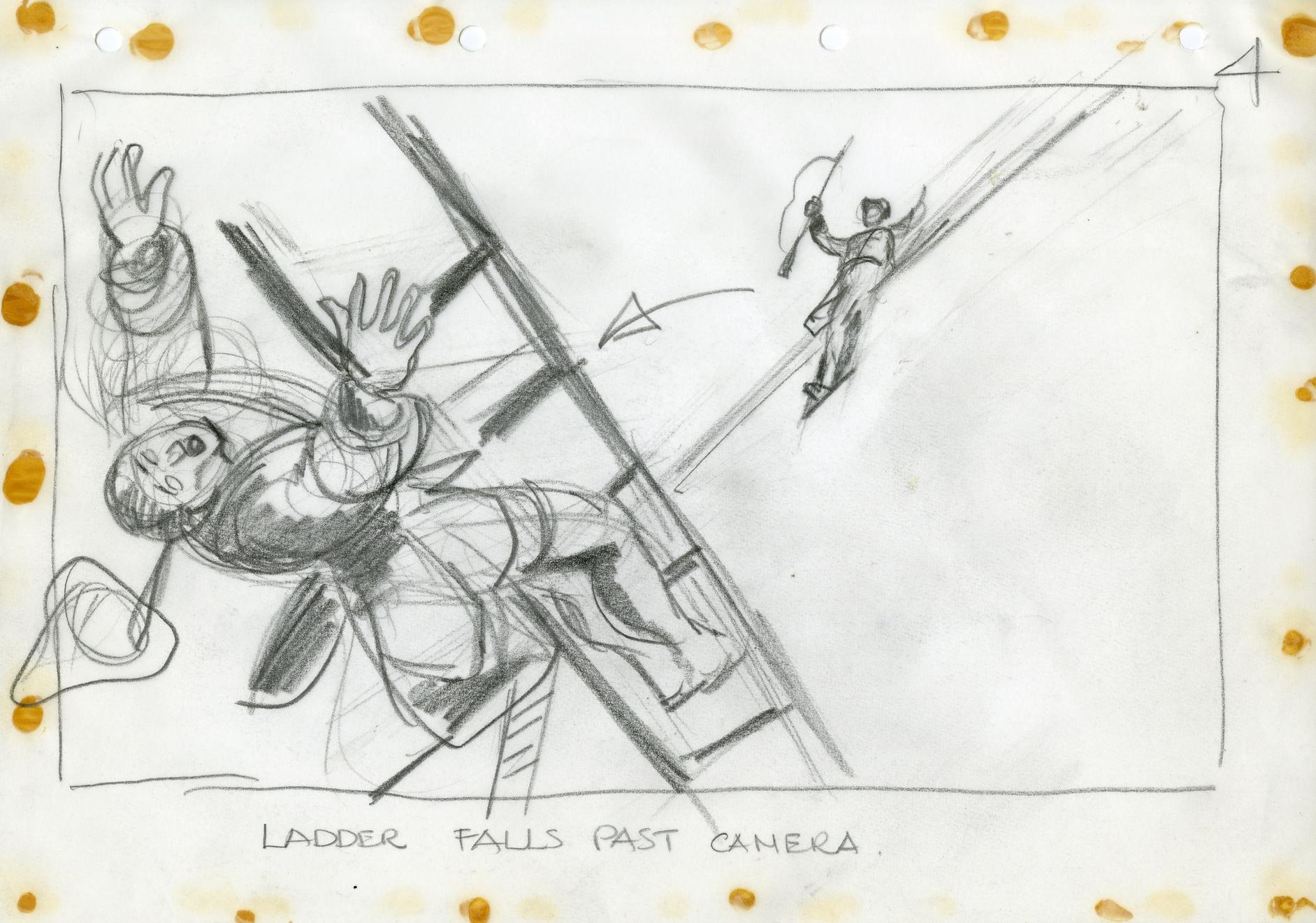

VISUALISATION DRAWING

Jan Harlan: “Storyboard is not the right word for what this is; Stanley did not construct his sequences in that kind of detail, but he certainly prepared himself well. Barry Lyndon has all these battle scenes, with lots of action, and Stanley would say: ‘How are we going to do this? I want some action.’ The art department would then come up with a visualisation of how to do a scene. Stanley wouldn’t have done this drawing himself; he was not a great pencil illustrator.” Photograph: SK Film Archives LLC, Warner Bros. and University of the Arts London.

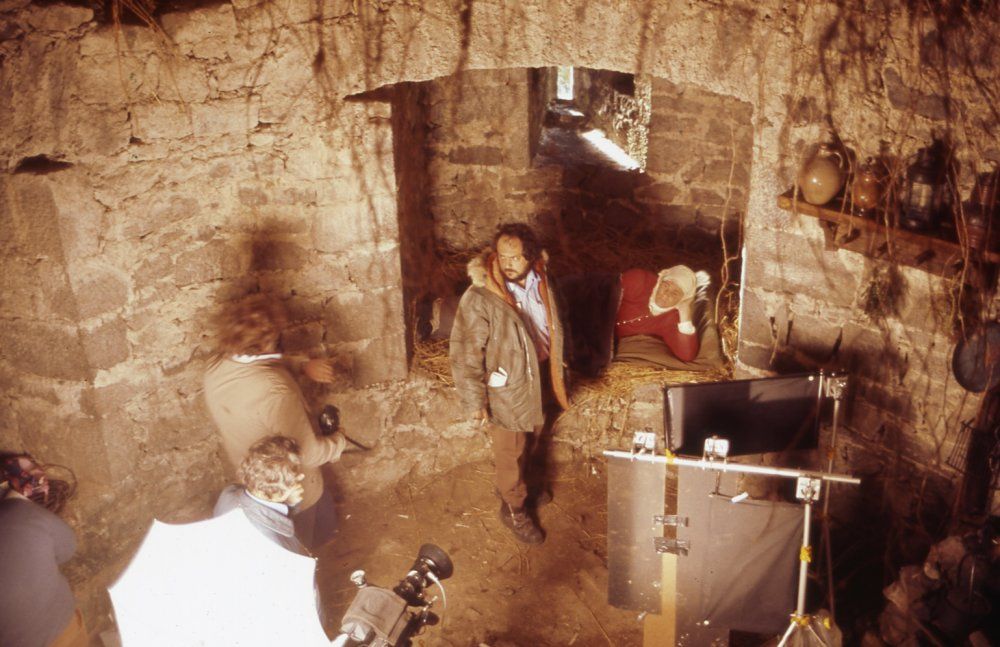

KUBRICK WITH THE CAST AND CREW DURING SHOOTING

The archive holds two boxes of production stills from the filming of Barry Lyndon. Still photographer: Keith Hamshere; SK Film Archives LLC; Warner Bros. and University of the Arts London. Courtesy of The Guardian & Hollywood in Éirinn.

MEMO OF ‘KEY WORRIES’

Jan Harlan: “Stanley didn’t like travelling. At the time he lived in Elstree, and he was hoping to do the whole thing in the studio down the road with a front projection system he had used in the ape scenes on 2001. That’s why the memo starts off with the front projection screens. But he had to abandon the idea after (production designer) Ken Adam convinced him it wouldn’t look right.” Photograph: SK Film Archives LLC; Warner Bros. and University of the Arts London. Courtesy of The Guardian.

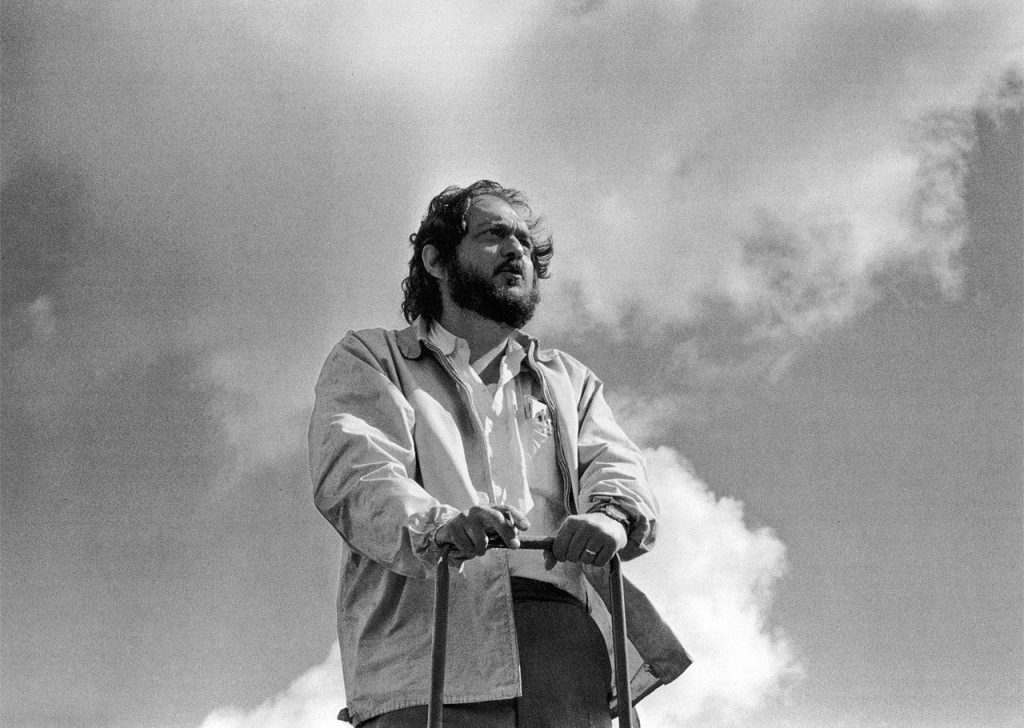

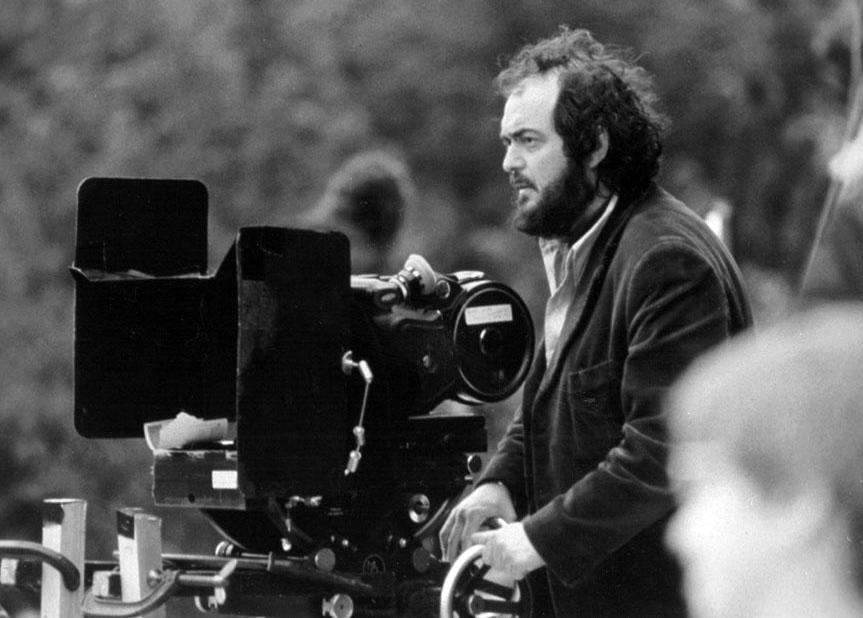

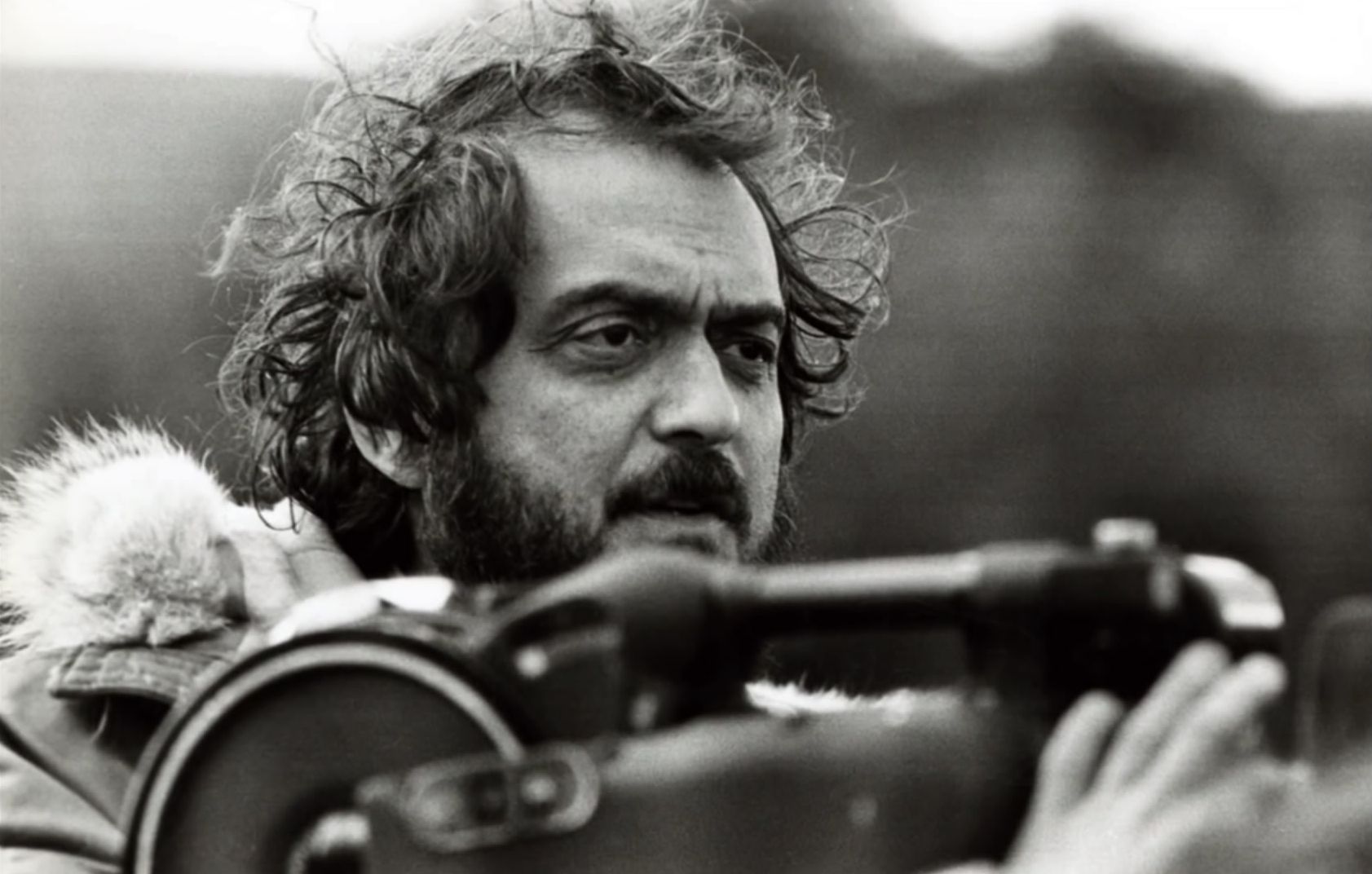

STANLEY KUBRICK MAKING ‘BARRY LYNDON’

Exclusive behind-the-scenes images showing Stanley Kubrick in production on his lavish 18th-century period masterpiece Barry Lyndon. Still photographer: Keith Hamshere. Credit: With thanks to the SK Film Archives LLC, Warner Bros. and University of the Arts London. Courtesy of British Film Institute.

Kubrick and O’Neal chatting during filming of the communal dinner scene in Barry’s Irish hometown. It’s at this table that Barry comes to blows with his love rival John Quin (Leonard Rossiter), a British army captain—the conflict that sets our hero’s adventures in motion.

Kubrick setting up a shot with Ryan O’Neal.

Kubrick surveys the scene from atop the camera platform, as his crew and extras mingle below.

The director prepares a shot. His cinematographer on the film was John Alcott, who won the Oscar for best cinematography on what is often referred to as one of the most beautiful films ever made. Alcott also collaborated with Kubrick on A Clockwork Orange (1971) and The Shining (1980).

Filming the bare-knuckle brawl at the army encampment, in which Barry is pitted into combat with a troublemaker called Toole. Toole is played by actor and wrestler Pat Roach, who would later turn up as various strongmen in the first three Indiana Jones films, Clash of the Titans (1981) and Never Say Never Again (1983).

Kubrick with actor Patrick Magee as the Chevalier de Balibari. Barry is employed by the Prussians to befriend the Chevalier, whom they suspect is a spy, and to report on his activities.

Kubrick shares a joke with O’Neal and Berenson.

Surveilling the scene from on high. Notice the floral garden chair with the words ‘Stanley Kubrick’ emblazoned on the back—a picnic-ready alternative to the traditional director’s chair.

PHOTOGRAPHING STANLEY KUBRICK’S ‘BARRY LYNDON’

American Cinematographer

March 1976 edition of American Cinematographer Magazine with two Kubrick-related articles, each covering the photographing of the film Barry Lyndon. One article focuses generally on the cinematography by John Alcott, while the other focuses more closely on the specialized lenses utilized for the film. Subscribing to American Cinematographer is highly recommended.

Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon is often lauded as one of the greatest achievements in the history of cinematography. And in a decade or even a year with some of the toughest competition you can think of, Barry Lyndon always seems to stick out just a little bit more. But what sets the cinematography of Barry Lyndon apart from other movies? And how was it done? Another excellent video essay by CinemaTyler.

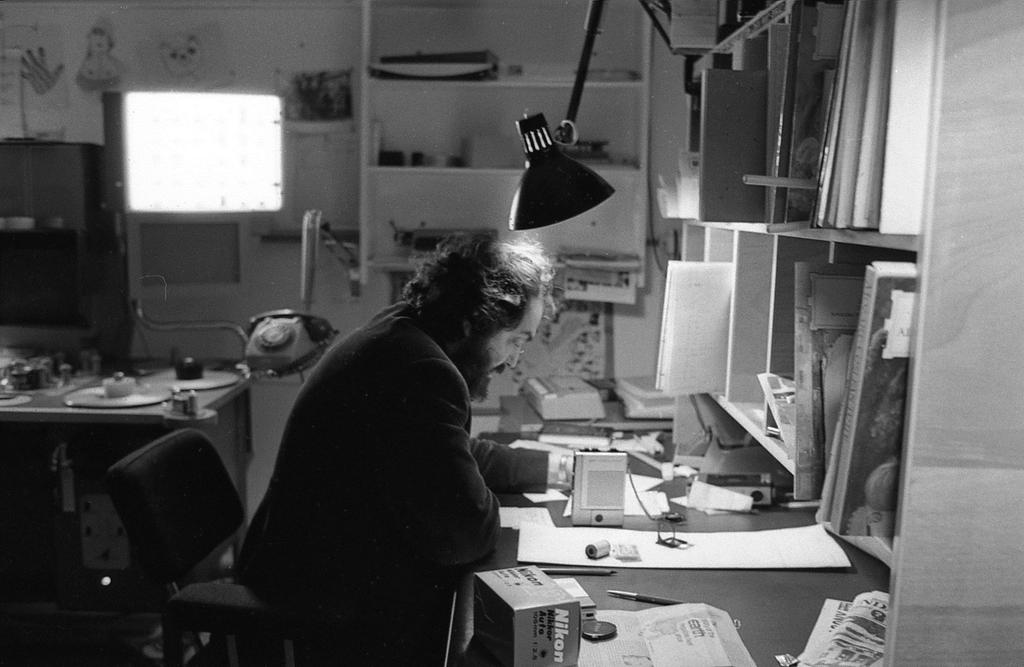

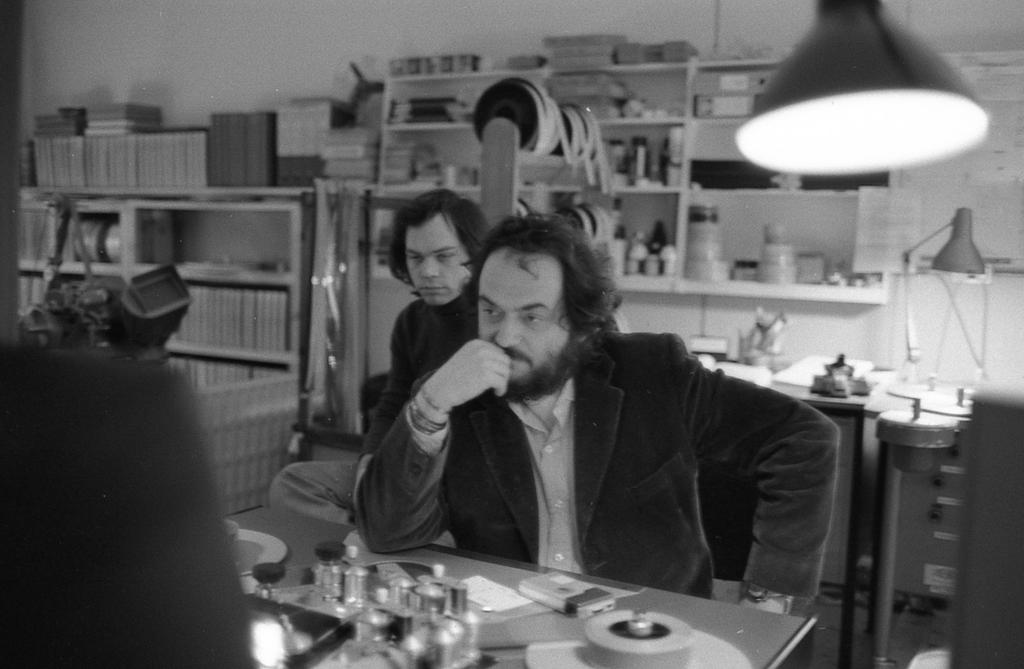

Previously unseen photos of Stanley Kubrick editing Barry Lyndon in the converted garage of his home in Abbots Mead, December 1974. Many thanks to Vivian Kubrick for sharing these amazing photos.

Documentary excerpt detailing the production of Kubrick’s masterpiece. Interviewees reminisce on how Kubrick acquired the Mitchell BNC cameras and used them, in conjunction with NASA Zeiss lenses, to film Barry Lyndon using natural light.

CASTLES, CANDLES AND KUBRICK

In the summer of 1973, director Stanley Kubrick arrived in Ireland to make his period masterpiece Barry Lyndon. On an overcast night the following January, the director fled Ireland on a ferry from Dun Laoghaire. Within 48 hours the entire production also abandoned their stations. Produced by Pavel Barter, Castles, Candles and Kubrick tells, for the first time, the story behind the making of Barry Lyndon in Ireland, featuring interviews with cast and crew from the film.

HOLLYWOOD IN ÉIRINN

Subtitled Irish language documentary on Kubrick shooting Barry Lyndon in Ireland. When a major movie production machine rumbles into town, anything can happen and frequently does. An invigorating injection of magic, money and mayhem arrives along with it, all contributing to a wild sense of excitement and anticipation. Denis Conway travels to four such locations, small villages and towns, in search of the memories of residents who witnessed the high and low jinks during the making of four major Hollywood blockbusters: The Wind That Shakes the Barley, Barry Lyndon, Moby Dick and Song for A Raggy Boy. Contributors include film actors Aidan Quinn, Iain Glenn, Jan Harlan and Pádraig Delaney. Produced by Seabed Productions.

KUBRICK RECALLED BY LEGENDARY SET DESIGNER SIR KEN ADAM

“In 1972 he approached me about designing Barry Lyndon but I think he decided I was too expensive and he employed someone else. Three weeks later I was in the south of France doing a film and the phone went. “It was Stanley sounding like a little New York boy: he said the designer hadn’t worked out and he needed me. He schmoozed me into doing the film and I was never happy about it.” Barry Lyndon was an ambitious historical epic to be shot on location. But there was a problem: Kubrick wanted to find locations while barely leaving his family home in Elstree, north of London. “So we set up in his garage a little war room, with Ordnance Survey maps on the walls and pins everywhere. We had an army of young photographers to go looking at buildings and possible locations and every evening we looked at what they’d done. “He would be enthusiastic about a particular bed or whatever in a slightly voyeuristic way. “But we’d have big arguments because I would say: ‘No that’s Victorian but the film is set in Georgian times.’ Well Stanley was so competitive that he bought almost every book available on Georgian architecture so he could argue with me. But none of this was getting the movie made because the buildings and peaceful locations he wanted just don’t exist anymore near London.

“It was nerve-destroying. But after five months I got Stanley to switch production to the Republic of Ireland—which I thought was my masterstroke.” As Sir Ken recalls it, once in Ireland Kubrick changed totally. “He saw himself as General Rommel, who he admired greatly. He equipped all of us with Volkswagens so we became a complete mobile unit driving around Ireland finding locations. “I spent weeks being chased through fields by bloody bulls. I was going crazy but this was Stanley’s character—with all his fears and anxieties he was relentless.” When Letizia, Sir Ken’s Italian-born wife, came out to Ireland she was shocked at his state of mind. She persuaded him to return to England and see a doctor for the sake of his health. “So now I was in hospital in England with a breakdown. Stanley rang the hospital every day to see how I was doing and if I was still alive. The day I left he phoned me at home. “He said: ‘Ken you were right: we’re going to change the way we’re making the film and you’ll love it. I’m sending a second unit to Potsdam in Germany to pick up extra material and I want you to direct it.” Sir Ken laughs. “Well I found that idea such a huge shock I had to go straight back to the clinic and check in again.”

After Barry Lyndon, Sir Ken decided this time, whatever his admiration for Kubrick, the two would never work together again. It was a vow he adhered to with one brief and slightly bizarre exception. In 1977, designing the Bond film The Spy Who Loved Me, Sir Ken had built a vast set at Pinewood studios. It included a supertanker which was proving hard to light.” So I called Stanley up and asked him down to Pinewood to give me ideas. At first he said I was out of my mind but eventually he agreed to come on a Sunday when only security were around. “He spent three or four hours with me telling me how he would light the stage. And of course the whole thing being in secret appealed to Stanley’s sense of drama. But I knew we would never work together again. And Stanley didn’t ask—he’d been so scared when he saw what happened to me half way through Barry Lyndon.” —Kubrick recalled by influential set designer Sir Ken Adam

KUBRICK’S GRANDEST GAMBLE

TIME magazine on Barry Lyndon and its director: “In a December 1975 cover story, TIME Magazine examines Barry Lyndon and the many paradoxes of Stanley Kubrick, covering the filmmaker’s Herculean task in bringing the 18th century novel by William Makepeace Thackeray to the screen and the near impossibility of selling a three hour art film spectacle to the masses. Read the full PDF.” —New Beverly Cinema

Loading...

Loading...

SIX KINDS OF LIGHT: JOHN ALCOTT

John Alcott, the great cinematographer who worked with Stanley Kubrick for some time, speaks at length about Kubrick and his additional work on 2001: A Space Odyssey, for which he took over as lighting cameraman from Geoffrey Unsworth in mid-shoot, A Clockwork Orange, Barry Lyndon, the film for which he won his Oscar, andThe Shining. Kubrick promoted Alcott to lighting cameraman in 1968 while working on 2001: A Space Odyssey and from there the two created an inseparable collaboration, in which they worked together on more than one occasion. In 1971, Kubrick then elevated Alcott to director of photography on A Clockwork Orange. Alcott studied lighting and how the light fell in the rooms of a set. He would do this so that when he shot his work it would look like natural lighting, not stage lighting. It was this extra work and research that made his films look so visually beautiful. Along with his Academy award for Barry Lyndon, the film is considered to be one of the greatest and most beautiful movies made in terms of its visuals. Not one, but three films worked on by Alcott were ranked between 1950–1997 in the top 20 of ‘Best Shot,’ voted by the American Society of Cinematographers. Yet another great accomplishment made possible by John Alcott.

Six Kinds Of Light (Masters Of Cinematography), a look at the work of six cinematographers—including Gordon Willis; Vilmos Zsigmond; Sven Nykvist, and, of course, John Alcott—was shown on PBS as part of their Film On Film series in 1986. A huge thanks to the original uploader, J Willoughby.

An interview with Kubrick from a conversation he had with French film critic Michel Ciment, in which he specifically discusses Barry Lyndon, The Shining and Full Metal Jacket. Additional text excerpt from a Ciment/Kubrick interview available here.

During a break in filming Pat Heavin approached O’Neal for a photograph. “I was a member of the Waterford Camera Club at the time. I was conscious that no press were allowed on set so I kept it very low key. I asked Ryan O’Neal if I could take his picture. He was extremely friendly to me.” Then he spotted the famously irascible Kubrick, who hated being photographed, taking a break. “I said ‘To hell with it. I’ll go for broke.’ I asked if I could take his picture and with a bit of encouragement from Ryan O’Neal, Stanley smiled and I had my picture.” Kubrick is seen smiling in the photograph, something he rarely did and certainly not for the press. Heavin says he respected the circumstances in which he was allowed to take the photographs and has never released them publicly before now. —When Ryan O’Neal and Stanley Kubrick made a film in Waterford

Here are some great photos taken behind-the-scenes during production of Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon. Photographed by Keith Hamshere © Peregrine, Hawk Films, Warner Bros. Kubrick on the set of Barry Lyndon, Waterford in 1973 by Pat Heavin. Photographs: SK Film Archives LLC, Warner Bros. and University of the Arts London. Courtesy of British Film Institute. Intended for editorial use only. All material for educational and noncommercial purposes only.

If you find Cinephilia & Beyond useful and inspiring, please consider making a small donation. Your generosity preserves film knowledge for future generations. To donate, please visit our donation page, or click on the icon below:

Get Cinephilia & Beyond in your inbox by signing in

[newsletter]