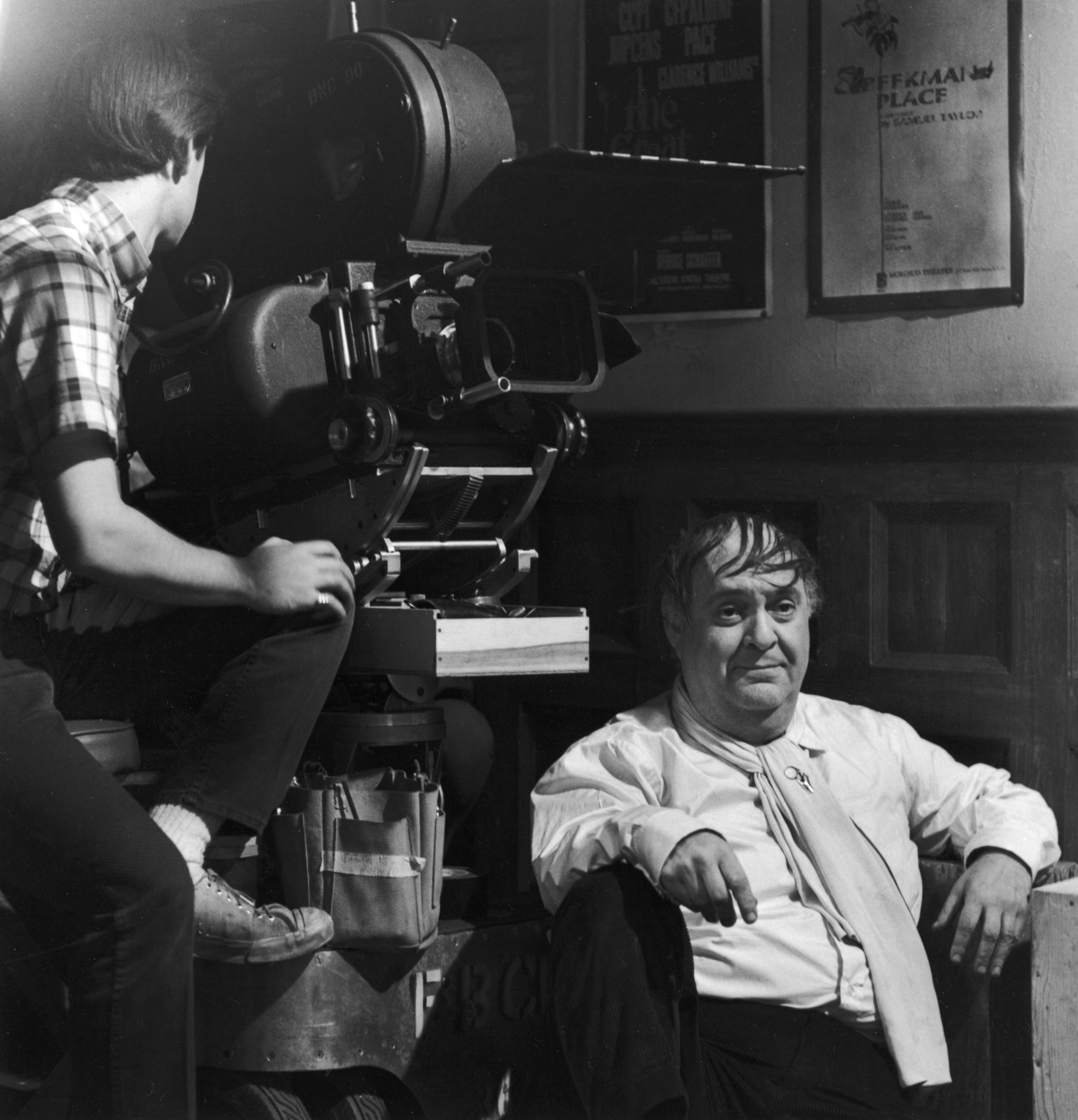

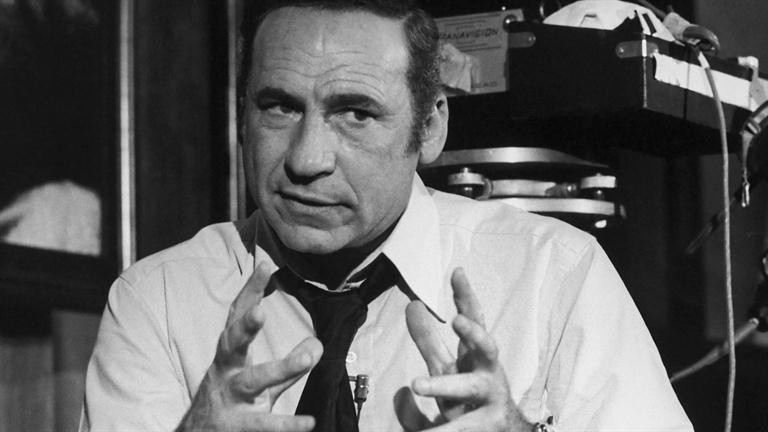

The American 1968 dark comedy The Producers was written and directed by the one and only Mel Brooks, the absolute king of satire and parody. The story of a desperate Broadway producer so poor he actually wears a cardboard belt who decides to make a lot of money by deliberately producing a disastrous play (and keeping the producers’ money in his pockets) is actually a very clever, full-frontal attack on the ethics at the heart of Broadway and the film industry. The Producers is a roller-coaster of low humor, cheap shots and silly, childish gags, but at the same time a work of tremendous energy, frenetic pace and marvelously inspired acting performances. The American comedian and actor Zero Mostel is instrumental here, but without Gene Wilder’s dedicated interpretation the film wouldn’t have had the kind of impact it enjoyed when it started winning over the audiences at the rise of VHS.

This film transformed Wilder into a star, but it also established the producer and comedy writer Mel Brooks as a highly promising filmmaker. The Producers, after all, got him the Academy Award in the Best Original Screenplay category. Brooks, who would a couple of years later create the lauded classics such as Blazing Saddles and Young Frankenstein (both with Wilder!), later returned to the film that jump-started his career: in 2001, he produced a Broadway adaptation of the film with Matthew Broderick and Nathan Lane in lead roles. Observed in a historical sense and through the prism of its influence on the film industry, the importance of The Producers lies in the film’s successful attempt to bring the traditional American film humor of the Marx Brothers a bit closer to the contemporary audiences. Mel Brooks created an unyieldingly entertaining series of sketches and routines ranging from just good to downright hilarious, offering the audiences a strong dose of vulgar, tasteless humor that was perceived as incredibly refreshing and even revolutionary.

A monumentally important screenplay. Dear every screenwriter/filmmaker, read Mel Brooks’ screenplay for The Producers [PDF]. (NOTE: For educational and research purposes only). The DVD/Blu-ray of the film is available at Amazon and other online retailers. Absolutely our highest recommendation.

Loading...

Loading...

Mel Brooks explains the film’s remarkable journey, courtesy of the Guardian.

BROADWAY

“I worked for a producer who wore a chicken fat-stained homburg and a black alpaca coat. He pounced on little old ladies and would make love to them. They gave him money for his plays, and they were so grateful for his attention. Later on there were a couple of guys who were doing flop after flop and living like kings. A press agent told me, ‘God forbid they should ever get a hit, because they’d never be able to pay off the backers!’ I coupled the producer with these two crooks and—BANG!—there was my story.”

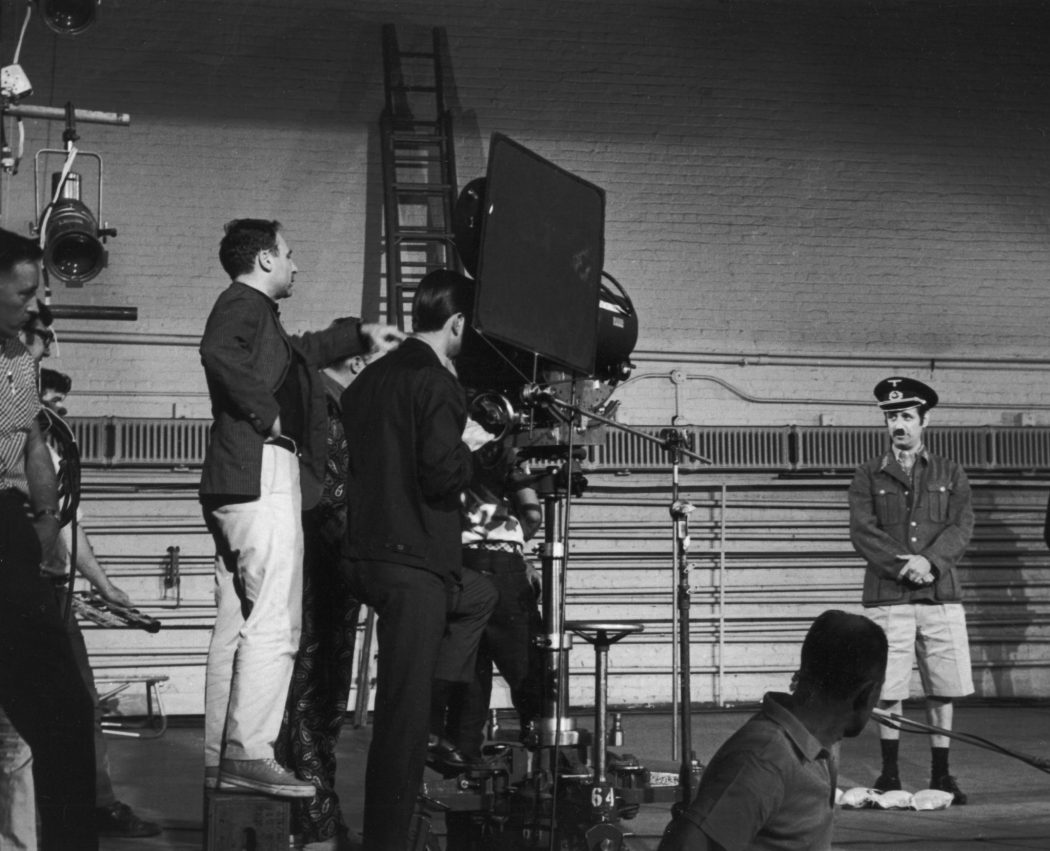

ADOLF HITLER

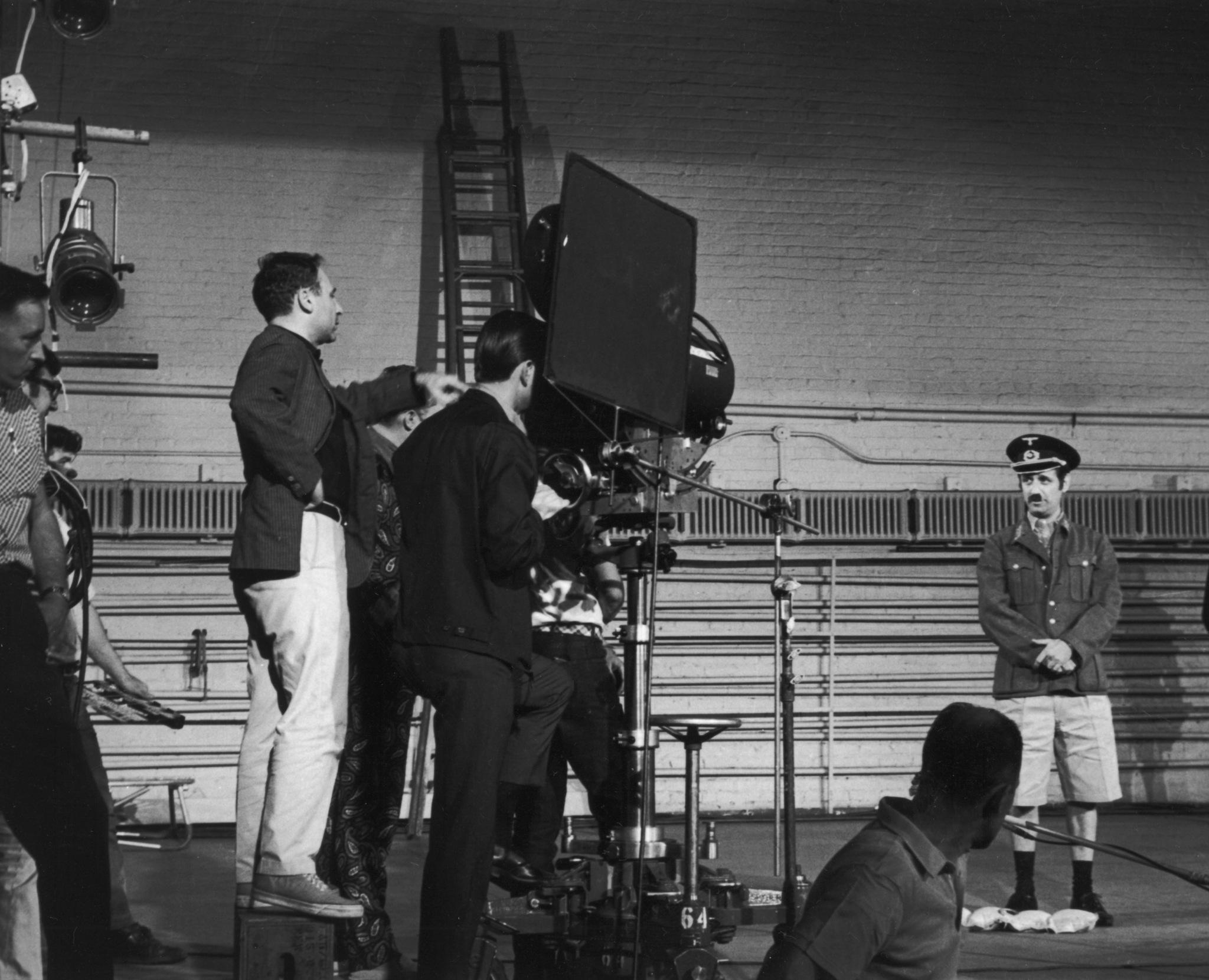

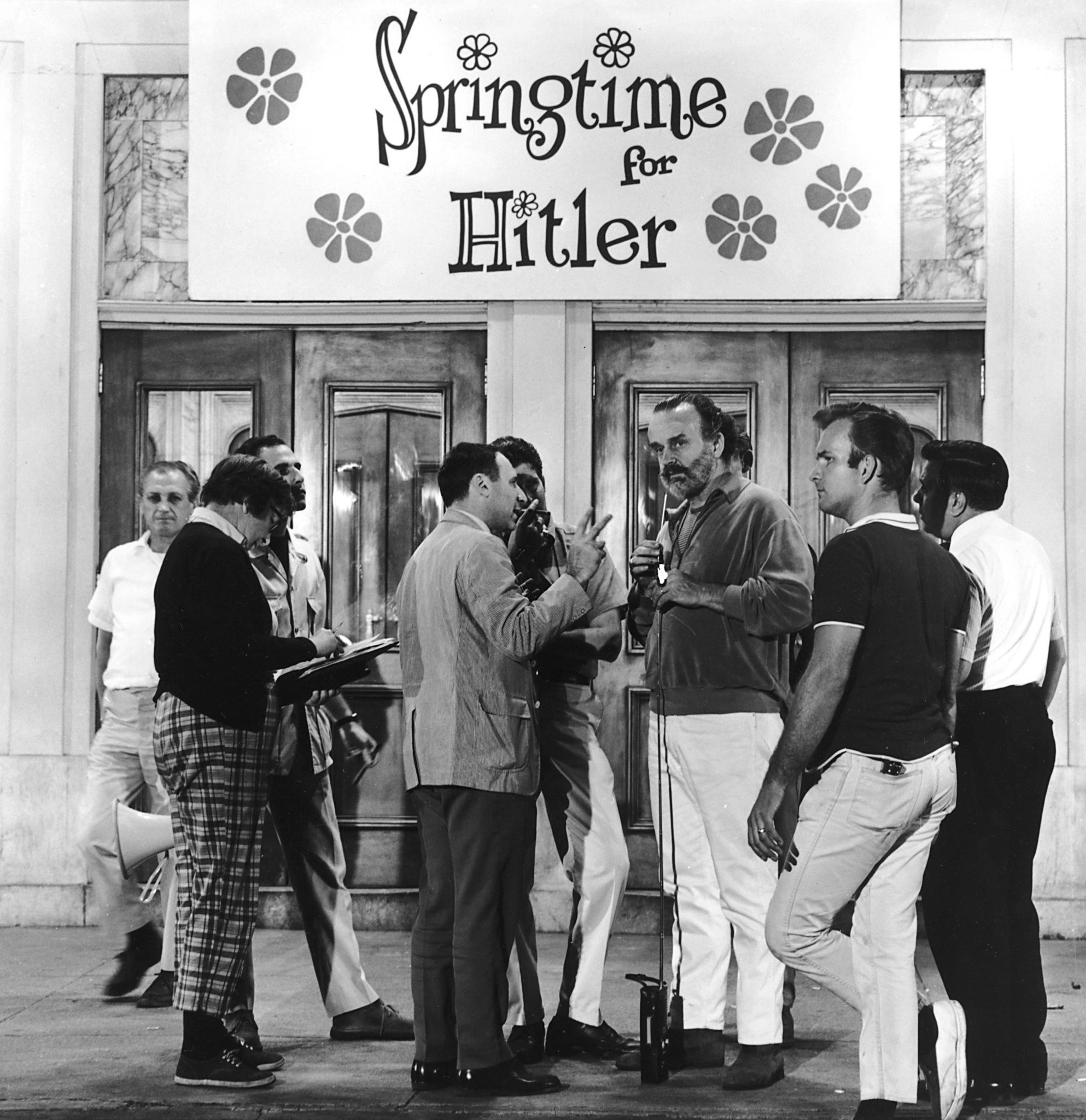

“It was such a delicious scheme, and I said to myself: so what is the flop? They’ve got to make a surefire flop, one that simply can’t run! But what would have people packing up and leaving the theatre even before the first act is over? Well, how about something about Hitler! How about a musical! A gay romp with Adolf and Eva in the Berchtesgaden! Well, that would certainly send the Jews flying out of the theatre! So that’s what I called my script: Springtime For Hitler.”

THE ORCHESTRA

“I only had eight weeks to get it all in the can, including a big production number, Springtime For Hitler. I was lucky to have John Morris as my composer. He’d never done a score before. I said, ‘Look, I’ve written a beautiful song called Springtime For Hitler. Forget the lyrics. If you sing the lyrics, it’s crazy, but if you just stay with the tune, it’s a very beautiful song, all you’ve got to do is play variations on that. When we have a sad scene, play it sad. When we have a happy scene, play it happy.’ He said, ‘Well, that’s a good start!'”

A TUNA SANDWICH

“Sidney Glazier was the only producer who would do this. He’d won an Academy award for The Eleanor Roosevelt Story, so I knew the guy had good taste, but I didn’t know why he’d want to do this crazy comedy. I went to see him, and he was eating a tuna fish sandwich, and he said, ‘Read it to me.’ So I began to read it to him… When I got to the part about Springtime For Hitler he exploded. He was choking with laughter; he came sputtering up from behind his desk and he said, ‘BY GOD, WE’LL MAKE THIS MOVIE!'”

HORSE RACING

“Sidney went to a guy called Louis Wolfson, a rich philanthropist. He also was a great racetrack enthusiast, so he was a gambler. And when he heard my idea, he said, ‘Oh good, this is getting back at Hitler. You can’t bring dictators down on a soapbox with rhetoric. But if you can make people LAUGH at them, you’ve won.’ He put up half the money. It cost $941,000 to make. The other half was put up by a producer called Joseph E Levine, who said, ‘I’ll do it if you change the title.’ That’s when we decided to call it The Producers.”

GENE WILDER’S EYES

“I found Gene in a Bertolt Brecht play called Mother Courage. My wife, Anne Bancroft, was starring in it, and Gene and I got to be friends. He’d say, ‘Why do people laugh at me?’ I said, ‘Because you’re a funny guy.’ He said, ‘But I don’t intend to be funny.’ I said, ‘That’s what comedy is all about: having the audience discover it.’ So I said, ‘I’m writing this script, and you’re going to be Leo Bloom.’ He said, ‘Ha ha, that’ll be the day!’ Then, two years later, I went back to him. By that time he had become a star, but he read the script and cried. Gene was nuts. Crazy. I loved Gene, because he was always an inch and a half away from hysteria. It was right there in his eyes. He was like a trapped animal and, in The Producers, Max Bialystock is the thing that’s trapping him.”

THE TUESDAY NIGHT GOURMET CLUB

“I knew it was always Zero Mostel that had to play Max Bialystock. Who else would pounce on old ladies to get the last dollar out of them? But Zero wouldn’t do it. Now, in those days I was part of a club called The Tuesday Night Gourmet Club, and we would meet at Chinese restaurants. It consisted of Speed Vogel, a clothing merchant and sculptor, and George Mandel, a novelist, who was best friends with Joseph Heller, and Joseph Heller was very good friends with Mario Puzo. Speed knew Zero’s wife, because they had a loft together where Speed sculpted and Zero painted, and Speed knew Kate, Zero’s Irish wife. He said, ‘Kate would love this, we gotta get it to Kate.’ So he gave her the script, she loved it, and she made Zero do it. She said, ‘No more sex,’ or something.”

PETER SELLERS

“Peter Sellers was a champion of The Producers and he nearly ruined it. It was about to open in England, and he took out a double-page ad in the Sunday Times that said, ‘This is the funniest and the best picture ever made.’ The critics said, ‘Hmm, we’ll be the judges of that, thank you.’ So I got good and bad reviews because they decided that they would judge it for themselves and not just take Peter Sellers’ word for it.”

FRANK SINATRA

“I only got one really great review at the time, and that was, ‘No one will be seated during the last 88 minutes—they’ll all be on the floor laughing.’ Oh, and someone at Newsweek said it was best lunatic humour since the Marx brothers invaded the opera. But word of mouth floated it, and the next year I found myself at the Oscars. Why? I don’t know! I was just lucky. I was up against Stanley Kubrick’s 2001! I was up against The Battle Of Algiers! I said, ‘Forget it.’ But sure enough, when Frank Sinatra was giving out the award, he said, ‘Best Original Screenplay… Mel Brooks!’ I got up and I took the award and I said, ‘I must tell you all what’s deep in my heart, what’s really in my heart.’ They waited, and I said, ‘Ba-DUM… Ba-DUM… Ba-DUM…’ And then I left!”

THE NEW YORK TIMES

“The first review, God bless the critics, was by Renata Adler in the New York Times. She crucified it. She said it was a lousy picture—not worth seeing. And when you do a little arts picture like that, you need the Times. You can’t survive without it. I don’t know what kept that movie alive! I mean, it wasn’t a Doris Day/Rock Hudson movie! It was definitely bizarre. Who would go see a film about Hitler and two Jews trying to outsmart their investors? Who cares about that?”

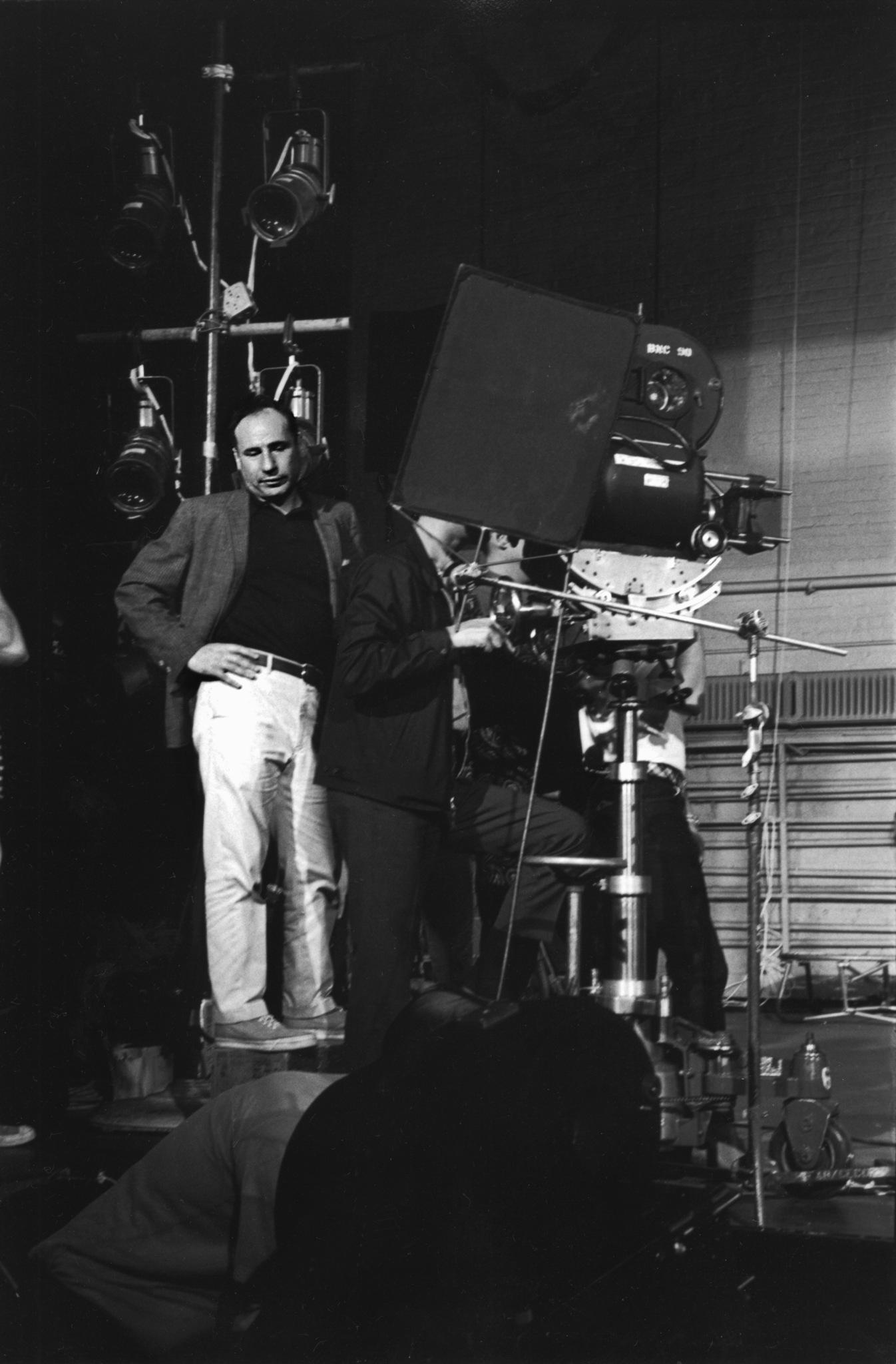

One of Mel Brooks’ biggest problems directing such classics as The Producers, Blazing Saddles, and Young Frankenstein was that his crew was always cracking up. With some of the most clever, hilarious, and outrageous moments ever put on film, who could blame them? —Quiet on the Set! by Robert Weide

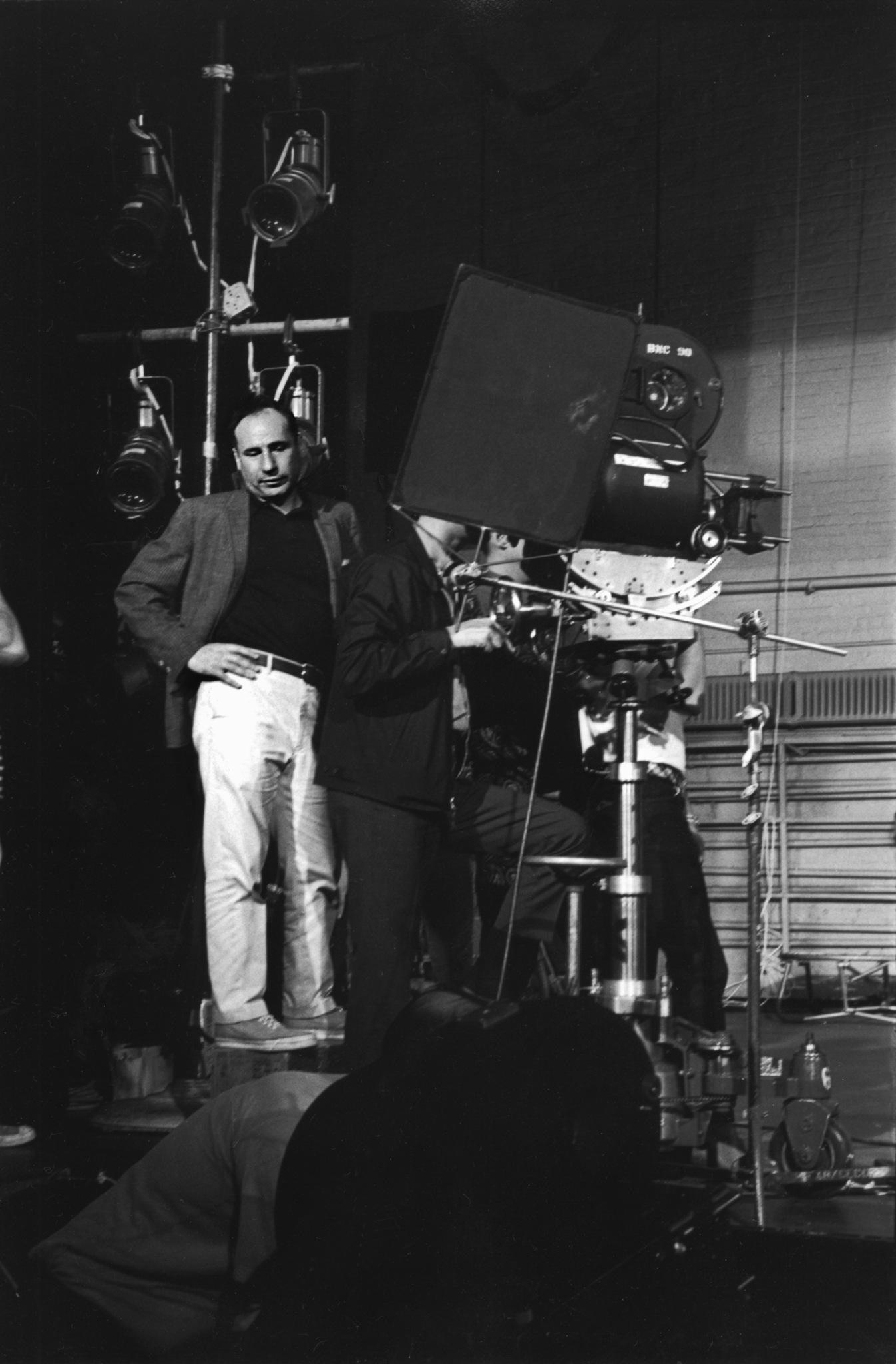

How did you convince anybody in 1968 to let you direct your first screenplay, The Producers, seeing as you hadn’t yet directed?

When I met [producer] Joseph E. Levine, he was making Hercules, and that was a big hit. And Hercules Unchained, then Hercules Nearly Chained, But Roped. I don’t know; he had a lot of Hercules pictures with chains. And he was making some money. So Levine says, ‘I’ll do it, but who are we going to get to direct it?’ And I said, ‘Me.’ And he said, ‘Oh no, you’ve never directed a picture. It’s still a million bucks, and we can’t afford to risk it.’ In those days it was a lot of money. And I said, ‘Joe, I’ve got the pictures in my head. I know what they look like; I know what they’re doing; I see them moving; I see them sitting; I see their expressions. I see it all lit, because I wrote it. If you get another director, they come in, they may have completely different pictures in their head. Maybe good, maybe bad, but it won’t flow.’ He said, ‘You know, that makes a lot of sense. Will you do it for scale?’ I said, ‘Of course, yeah, yeah. But I won’t direct it unless I get final cut, because I know what studios can do.’ So he gave me final cut.Did you just instinctively know how to get needed coverage of the scene, or was someone assigned to look over your shoulder?

I had a vague idea of coverage—of what might go wrong, of what might be a link shot or a fulcrum. I didn’t know that you could cut to an alarm clock or an ashtray. So there were a lot of tight shots and close-ups, which in my naiveté, saved me.I assumed all the close-ups in The Producers were there because if you have faces like Gene Wilder’s and Zero Mostel’s, you want to show them off. It never occurred to me that you simply lacked coverage.

Right. But I always had a place to rest on so I could get the best of the scene. And I had a great editor, Ralph Rosenblum. He later did Woody’s first picture. The truth is you cannot save a bad picture in the cutting room. You can help a good picture, though. And I’ve had some very good editors. John Howard, who I worked with a number of times, was also a wonderful editor.I’m guessing you’re very hands-on in the editing room.

Absolutely. It’s always been my thinking that the final editor should always be the director, and the director should always take a huge hand in the editing. I never did what a lot of directors do. They say, ‘Well, throw it together and let me take a look and then I’ll re-edit it, and we’ll work together.’ I would say, ‘Give me everything you’ve got: outtakes, the works, everything you’ve got.’ And I’d look at it all and spend a couple of days not editing, just looking. Running it through in my head.So you want to see every frame of footage.

Every frame. And I would ask: One, am I telling the story? Two, is it entertaining and interesting? Three, is it well-lit, or whatever directors like to talk about. And the first scene in The Producers took the longest time. It was the scene in which Zero Mostel is screwing this little old lady on the couch—Estelle Winwood, a marvelous actress. But it’s really the meeting of Bialystock and Bloom. I only had about 20 weeks to edit the whole [picture], but two very precious weeks were spent on the first scene.Do you remember your first day on the set? Did you feel you were in your element?

Yeah, I was thrilled. Michael Hertzberg was my 1st AD, and he was very wonderful and helpful. Sometimes he would take me by the collar and say, ‘We’re finished here.’ And he’d take me to a new set that was lit.That’s a good 1st AD.

Yeah, he was very good, and he knew how much money we had to work with. But on that first day, I wanted to give the crew an extra treat, and I didn’t want them to break for lunch, so I spent my own money and I went to Chock full o’Nuts and got dozens of sandwiches and gallons of coffee, but they wouldn’t let me back in. There was a new woman who took over the desk at 26th Street, and she wouldn’t let me in. Finally Hertzberg came out and said, ‘He’s the director, lady!’What was your shooting schedule like?

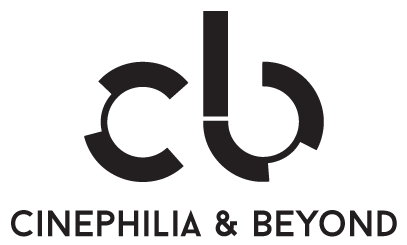

I only had 40 days to make the picture, including Springtime for Hitler, the big stage number, and the opening night, which I did at the 48th Street Theater. We only had the theater for two days to do everything, and I was given four cameras to do it. It was great. Alan Johnson, the choreographer, was sitting next to me. I said, ‘Alan, this is the only scene I’m spending money on.’ And what was wonderful about it was choreographers can bug the shit out of you. You know, ‘He missed that step … ‘ But he was so cooperative. I said, ‘Alan, we’re gonna do this as if it’s a documentary. We’re just going to cover it.’ We only did two takes of the whole number. But that was the hardest work and the most thrilling thing I’ve ever done in my life. The only other thing to compare to it was the scene at Lincoln Center. They got the fountain up to about 8 feet, just above the actors’ heads, which was wonderful. But I met somebody who said to me, ‘I’m one of the engineers who works on the fountain. I can get it up to 16 [feet].’ I said, ‘Could I see it at 16?’ And there it was. Sixteen feet of tons of water. And when Gene Wilder shouts, ‘I’ll do it, by God, I’ll do it!’ it was thrilling.That’s such an iconic scene.

And Joseph E. Levine, after seeing the first week of dailies said, ‘I’ll give you another $35,000 or $40,000 to get another actor. This guy Gene Wilder stinks.’ And I said, ‘Joe, trust me. It’s going to be all right. He’s very good. It’ll be fine.’ Anyway, I didn’t fire Gene. So we made it, and it was shown at the Lane Theater, somewhere in the suburbs of Philadelphia. And Levine came with three or four guys. There was a bag lady sitting in the second row just sleeping, and maybe three or four people scattered around this 1,500-seat theater.Was this a test or the actual opening?

It was a test to see how much money they would spend on advertising. The next day I met with Levine, and he said, ‘You know, we’re not going to go crazy on this. We’re going to be kind of conservative.’ He was being kind. So I said, ‘What is that? You’re going to spend about $200 on marketing?’ He said, ‘No, no, you can double or triple that.’On the surface, The Producers is simply good, silly fun. But do you take personal pleasure in the subversive element of making fun of Nazis? There are Nazi jokes in many of your movies.

Yeah. If you can make them seem foolish and silly, then you’ve won. But if you get on a soapbox and go head to head with Herr Hitler and Goebbels, you’re not going to win. They’re good at that shit. But they’re not good at comedy.

The Making of The Producers.

After 60 years in show business, Mel Brooks has earned more major awards than any other living entertainer; he is one of 14 EGOT (Emmy, Grammy, Oscar and Tony) winners. Yet, the comedy giant has energetically avoided a documentary profile being made, even issuing an informal gag order on his friends… until now.

Images courtesy of mptvimages.com, Photofest.

If you find Cinephilia & Beyond useful and inspiring, please consider making a small donation. Your generosity preserves film knowledge for future generations:

Get Cinephilia & Beyond in your inbox by signing in

[newsletter]