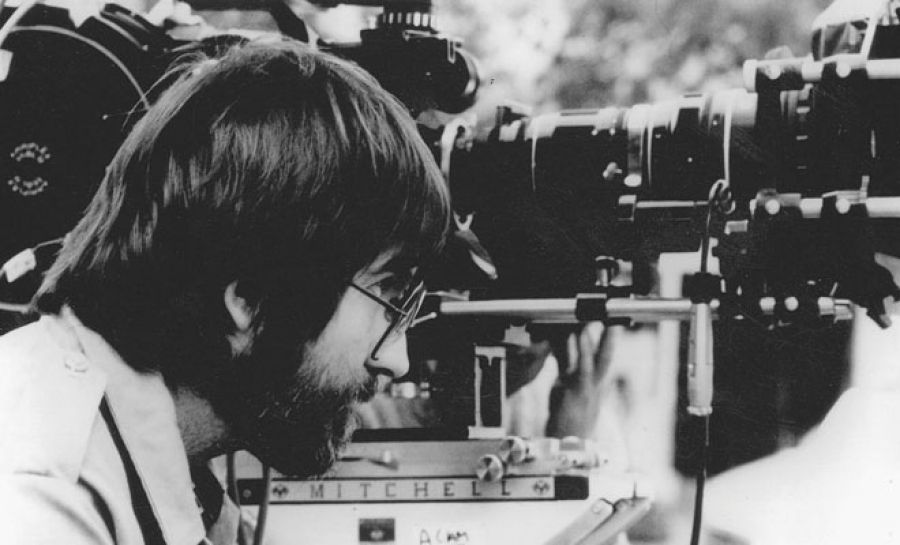

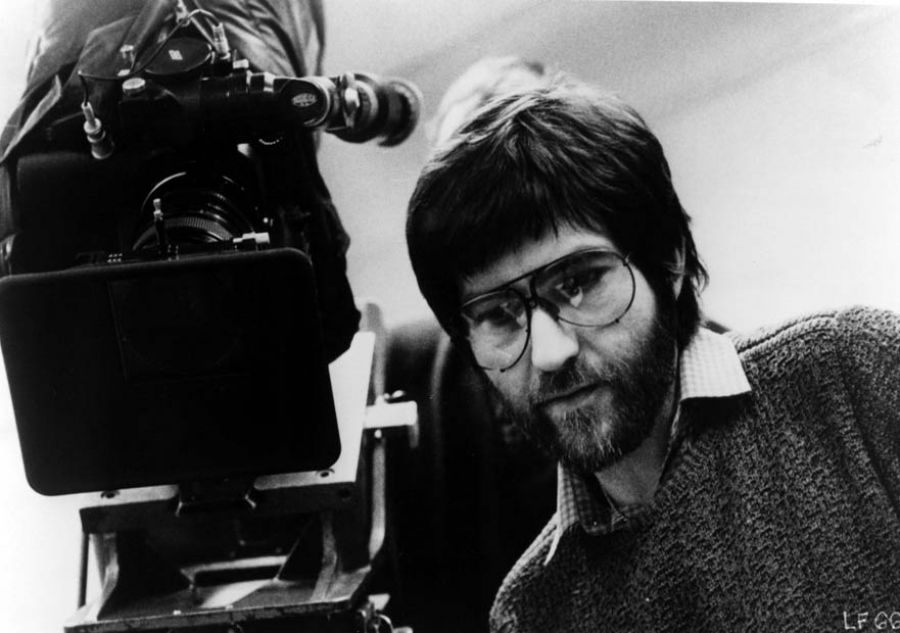

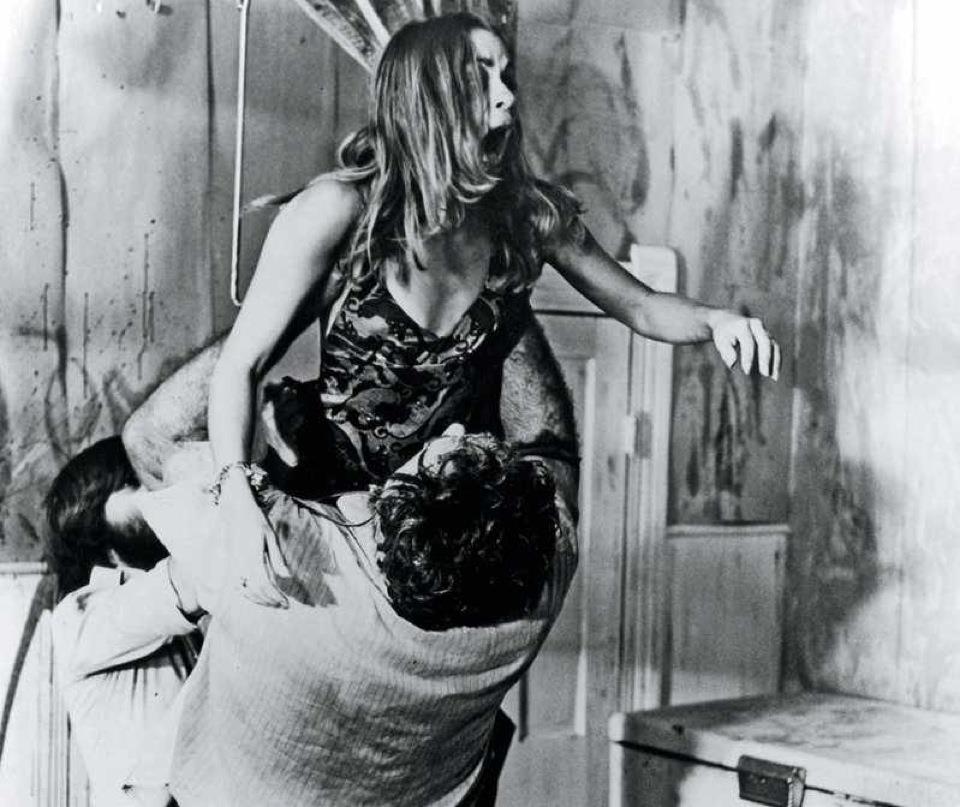

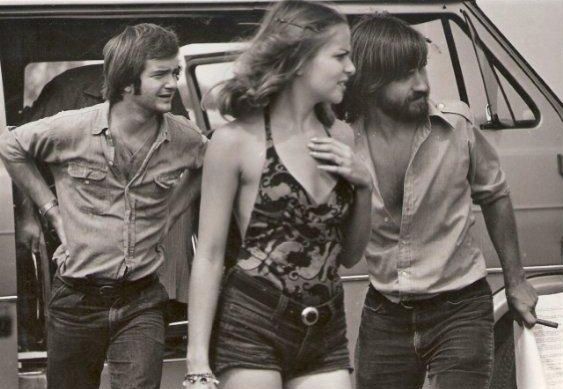

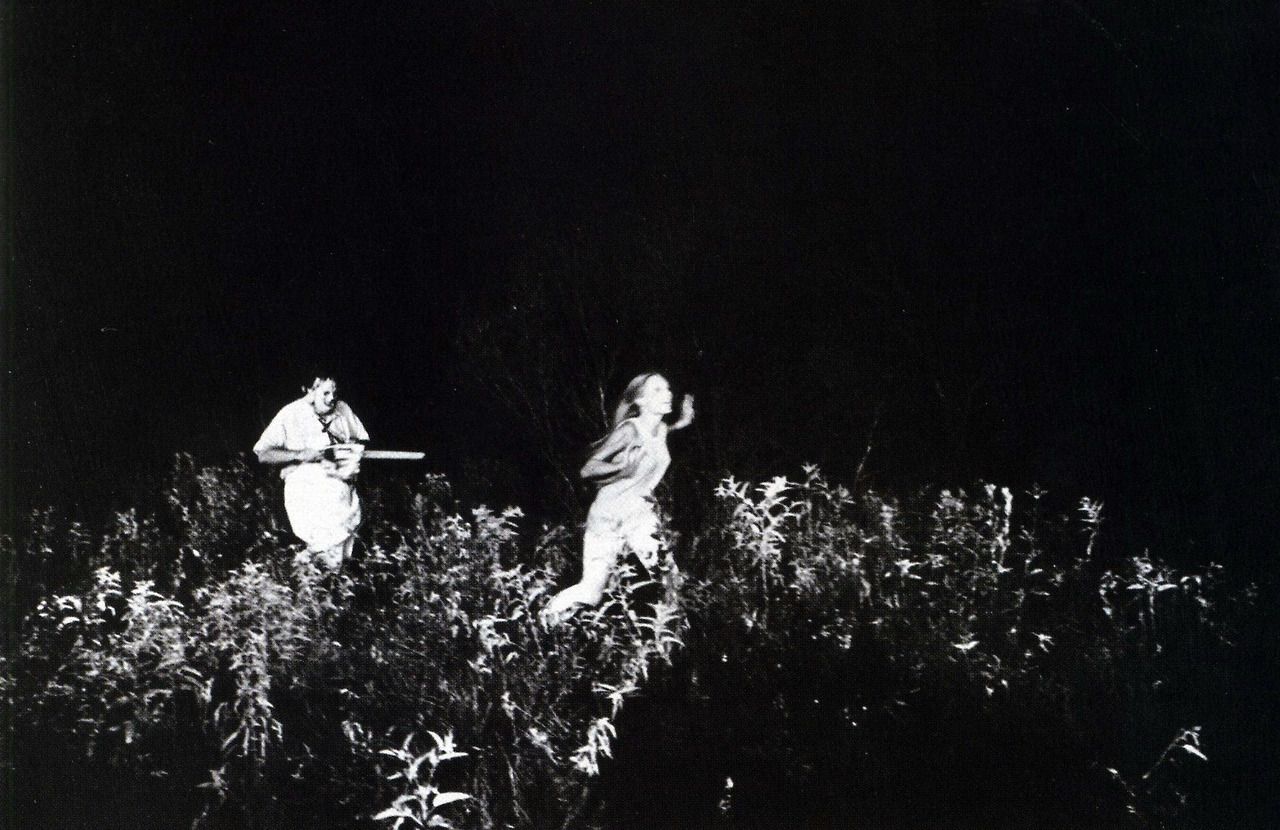

Hailed by many as the perfect horror film, lauded by millions as one of the most influential films ever made, considered by most one of the revolutionary pillars of latter day horror cinema, Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is an endlessly referenced cult slasher that beckons to be revisited every once in a while. Written and produced by Hooper and Kim Henkel, partly based on the story of the 1950s serial killer Ed Gein, it’s to no coincidence that countless all-time best lists reserve a spot at the top for this film. So what’s the deal with this seemingly gory slash fest? Why is it so important today, and what exactly separates it from the rest? Well, to answer these questions, one should note at the very start of an analysis that it’s incredibly effective. Fifteen years since seeing it for the first time, we still remember the inescapable terror freezing up our bone marrow. It’s staggeringly realistic: as the great Wes Craven once said, it “looked like someone stole a camera and started killing people.” A lot of this praise goes to Hooper’s talented cinematographer Daniel Pearl. This snuff quality makes it painfully easy for the viewer to forget they’re watching a fictional story, and the feeling of actually witnessing a series of real life brutal murders is abundantly helped by the fact that Hooper’s cast consisted of rather anonymous actors from the Texas area, which most likely had more to do with budgetary constraints than the filmmaker’s vision. It’s the same financial limitations that forced Hooper and his crew to work seven days a week up to 16 hours a day. Combine this with the exhausting weather conditions, when the temperature rose to 40 degrees Celsius, and it’s perhaps not so difficult to understand why the desperate, painful screams of the actors sound so real and unnerving.

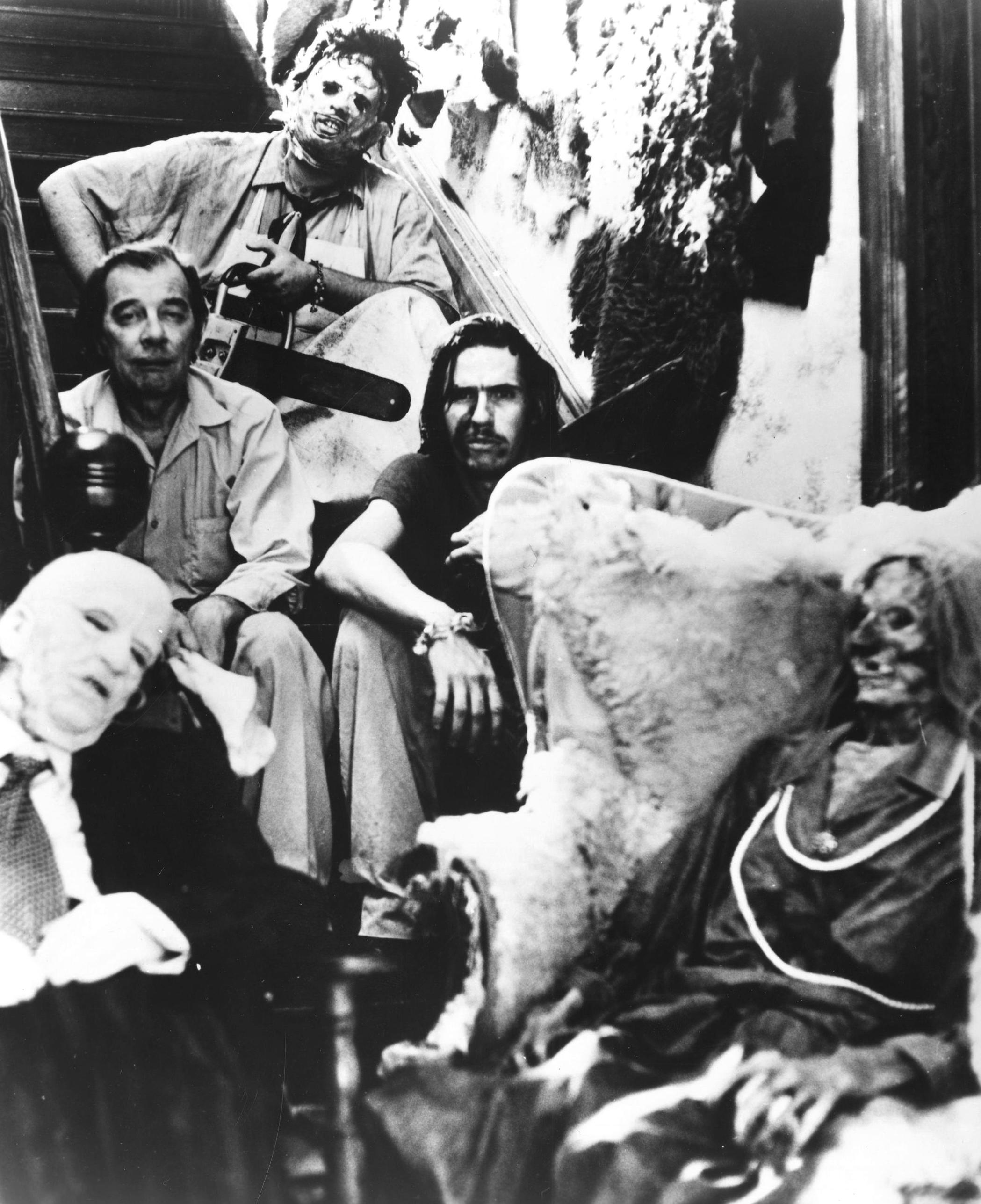

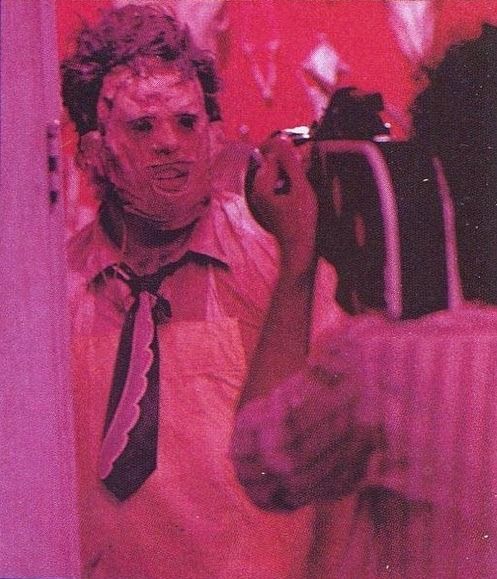

It’s impossible to talk about The Texas Chainsaw Massacre without referencing the influence it wielded on the horror film production that followed. The very concept—several ordinary people in wild, desolate surroundings faced with horrible, maniacal atrocities—has been copied endlessly up to this very day. Moreover, the legendary character of Leatherface, a towering figure of almost unnatural strength and tenacity but deprived of individuality and characterization, wearing a terrifying mask, became a role model for slasher icons that followed, as well as his use of motorized tools for destroying his victims. It’s rather curious to note that Hooper’s unsuccessful attempt to acquire a PG rating resulted in making the film even more petrifying. The filmmaker severely limited the quantity of onscreen gore, but this left plenty of implications and suggestions for the audience, which means quite a lot of the brutality and gruesomeness was left to the viewer’s imagination. These indirect subtleties, however, are far more effective than open, blunt portrayals of decapitation and gutting.

I knew it was going to get recognition, because it was so different. And I knew it was special. The films I had been watching before I made it were Fellini films, Antonioni, and Truffaut. I was at the art house a lot. And I had made about 60 documentaries and TV commercials, so I’d developed a style of fast cuts, almost as subliminal as you can get at 24 frames a second. But, yes, the film kept getting released after its first run, about eight times. You mention the horror genre, but the slasher-film concept didn’t really come about until years after this film. Probably it didn’t really start until Jason and Friday the 13th [1980]. And those films were made for shock value—splatter films or torture porn. —Tobe Hooper

Horror master Guillermo del Toro named Hooper’s film one of the top five horror films ever made, Nicolas Winding Refn said it was the film that attracted him to the filmmaking business, and this is just a small drop in the sea of appreciation the film’s been getting in the last couple of decades. Whatever layer of the film you decide to analyze and dissect, from whichever angle you choose to look at the movie, it’s simply a masterful, surprisingly artistic execution of a project developed in meager circumstances, which resulted in a timeless classic whose historical value, even if you fail to see its numerous qualities, simply can’t be denied.

Tobe Hooper was a maverick a rebel and gentle, kind soul. An unlikely combination and a great loss. He changed genre films forever.

— Guillermo del Toro (@RealGDT) August 27, 2017

A monumentally important screenplay. Screenwriter must-read: Kim Henkel & Tobe Hooper’s screenplay for The Texas Chain Saw Massacre [PDF]. (NOTE: For educational and research purposes only). The DVD/Blu-ray of the film is available at Amazon and other online retailers. Absolutely our highest recommendation.

Loading...

Loading...

The script was entitled Leatherface. At various points before the film’s release, the title was switched to Head Cheese and finally The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. The film’s original budget was $60,000; during the editing process, the filmmakers amassed an additional $80,000 in costs, requiring that they sell off portions of their ownership in the film’s royalties. —Texas Chainsaw Massacre 25 Things

Director Tobe Hooper discusses his breakthrough hit, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, one of the most successful and influential horror films ever made.

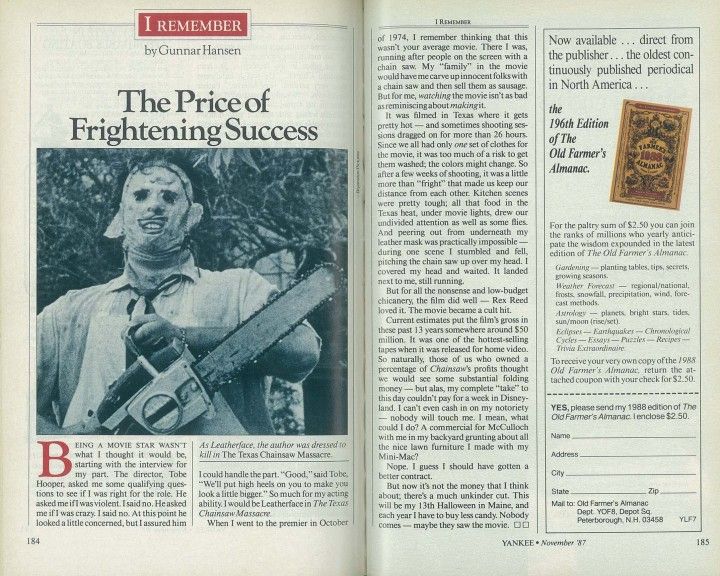

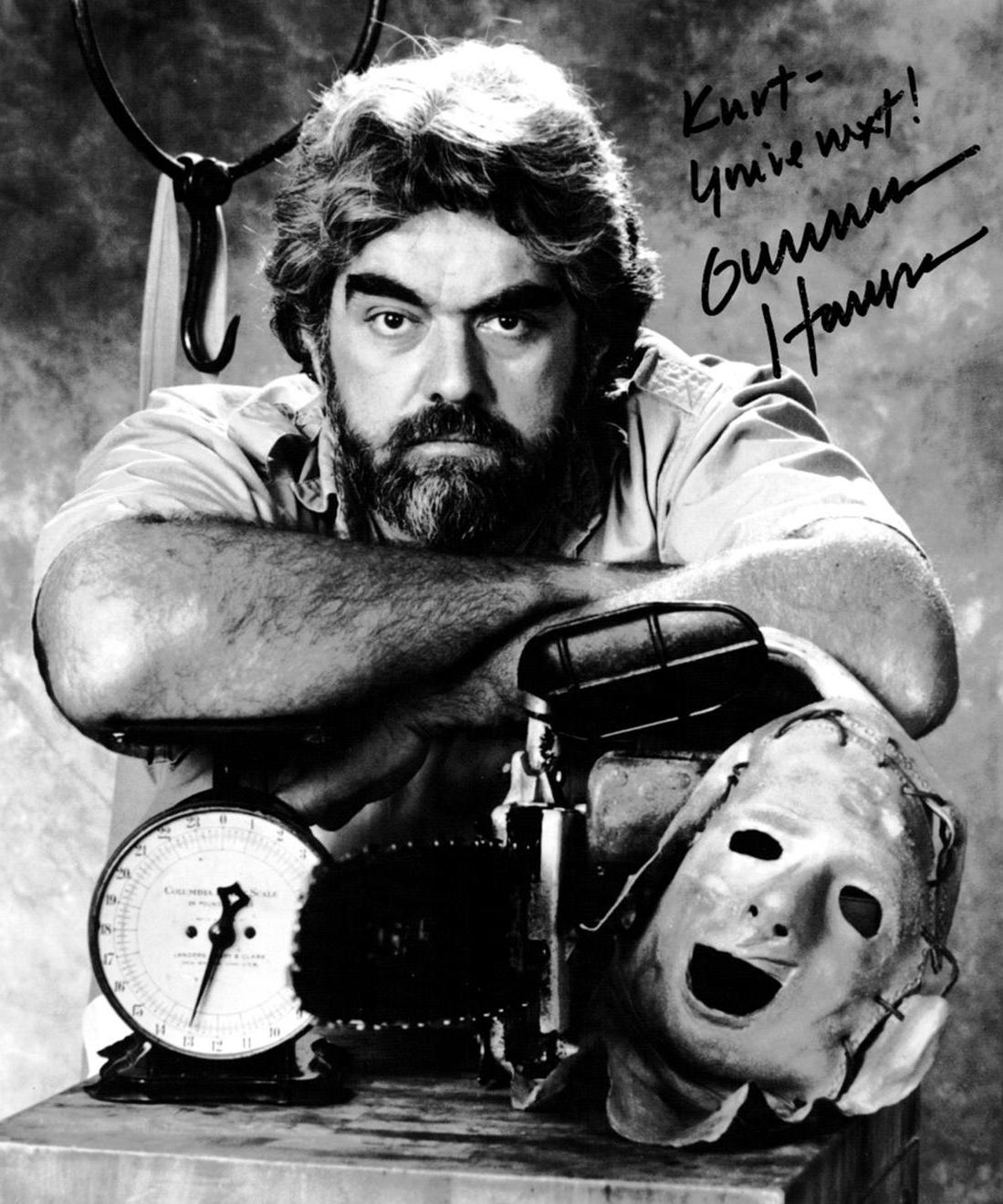

In 1987, Yankee Magazine asked Gunnar Hansen about his famous 1974 role as Leatherface in the cult horror movie classic, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Hansen spent his childhood years in Maine, and returned there in 1975 to begin a career in writing, which included appearances in Yankee. He passed away on November 7, 2015 at his home in Northeast Harbor. Excerpt from ‘The Price of Frightening Success,’ Yankee Magazine, November, 1987.

Being a movie star wasn’t what I thought it would be, starting with the interview for my part. The director, Tobe Hooper, asked me some qualifying questions to see if I was right for the role. He asked me if I was violent. I said no. He asked me if I was crazy, I said no. At this point he looked a little concerned, but I assured him I could handle the part. “Good,” said Tobe, “We’ll put high heels on you to make you look a little bigger.” So much for my acting ability. I would be Leatherface in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

When I went to the premier in October of 1974, I remember thinking that this wasn’t your average movie. There I was, running after people on the screen with a chain saw. My “family” in the movie would have me carve up innocent folks with a chain saw and then sell them as sausage. But for me, watching the movie isn’t as bad as reminiscing about making it.

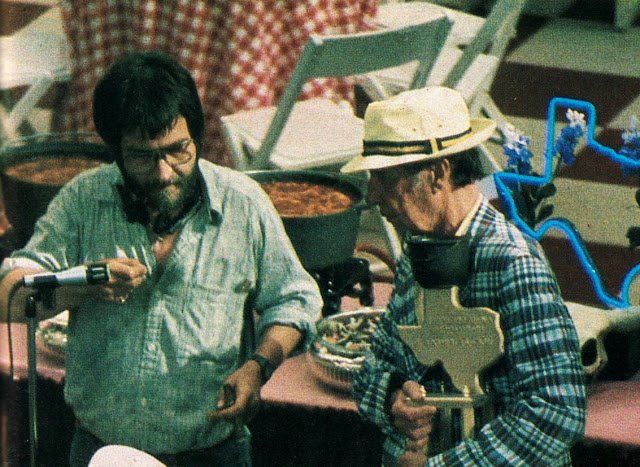

It was filmed in Texas where it gets pretty hot—and sometimes shooting sessions dragged on for more than 26 hours. Since we all had only one set of clothes for the movie, it was too much of a risk to get them washed; the colors might change. So after a few weeks of shooting, it was a little more than “fright” that made us keep our distance from each other. Kitchen scenes were pretty tough; all that food in the Texas heat, under movie lights, drew our undivided attention as well as some flies. And peering out from underneath my leather mask was practically impossible during one scene I stumbled and fell, pitching the chain saw up over my head. I covered my head and waited. It landed next to me, still running.

But for all the nonsense and low-budget chicanery, the film did well—Rex Reed loved it. The movie became a cult hit.

Current estimates put the film’s gross in these past 13 years somewhere around $50 million. It was one of the hottest-selling tapes when it was released for home video. So naturally, those of us who owned a percentage of Chainsaw’s profits thought we would see some substantial folding money—but alas, my complete “take” to this day couldn’t pay for a week in Disneyland. I can’t even cash in on my notoriety—nobody will touch me. I mean, what would I do? A commercial for McCulloch with me in my backyard grunting about all the nice lawn furniture I made with my Mini-Mac?

Nope. I guess I should have gotten a better contract.

But now it’s not the money that I think about; there’s a much unkinder cut. This will be my 13th Halloween in Maine, and each year I have to buy less candy. Nobody comes—maybe they saw the movie.

Hooper, an Austin-born filmmaker who was 30 years old when he shot this film, has gone on to make a dozen pictures (including directing 1982’s Poltergeist and 1986’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre 2). He lives in Los Angeles, and before a trip to Cannes to screen the restoration at the Directors’ Fortnight, he met up with designers Kate and Laura Mulleavy of Rodarte at a restaurant in downtown L.A. to discuss the making of his masterpiece. The Mulleavy sisters are horror-film aficionados who have used dark cinema as inspiration in their designs. Courtesy of Interview Magazine.

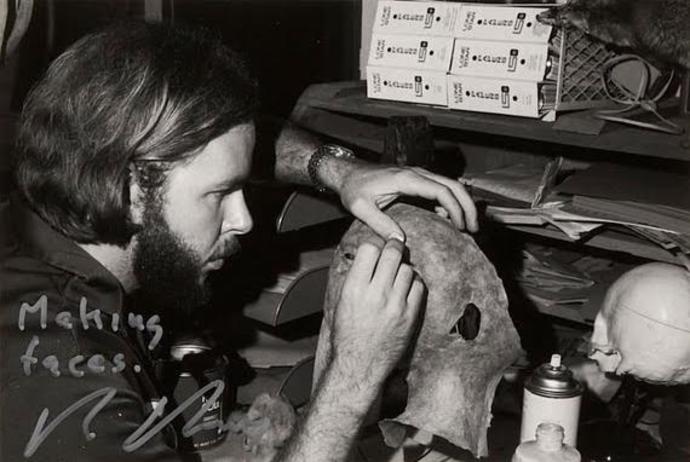

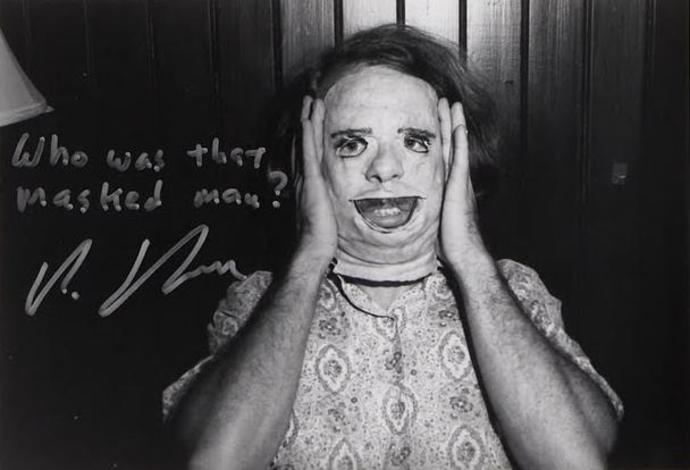

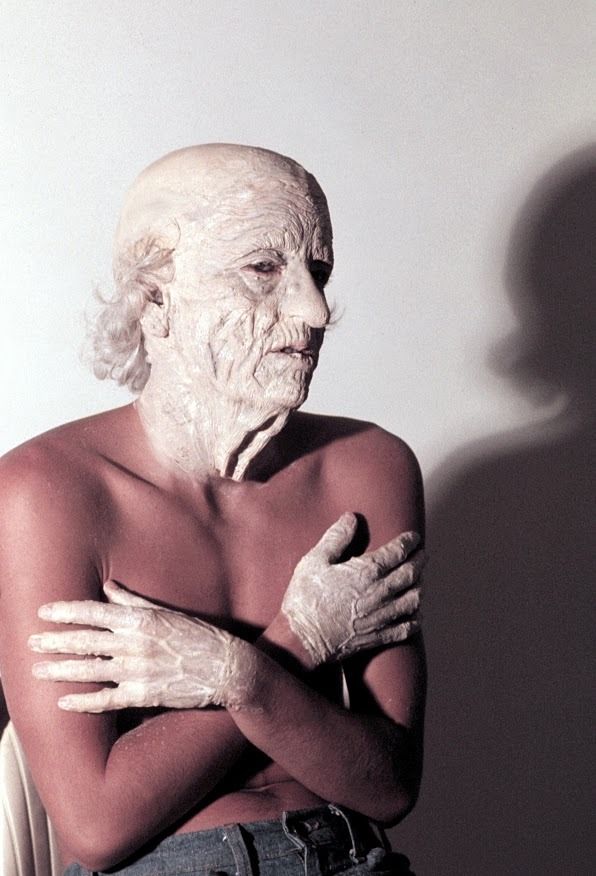

WHO WAS THAT MASKED MAN?

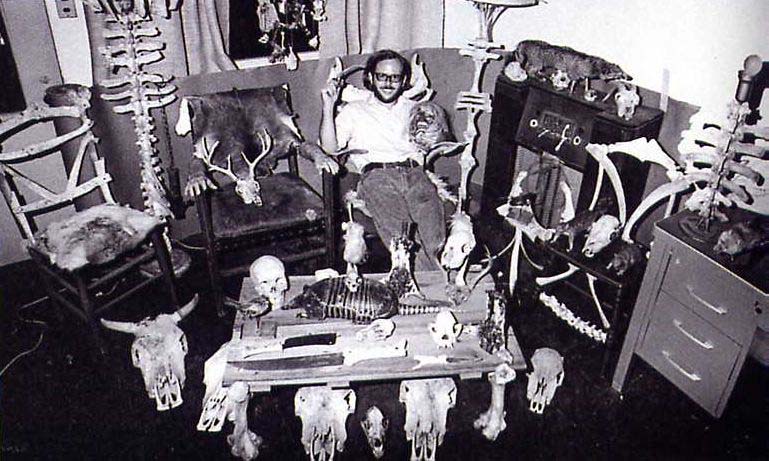

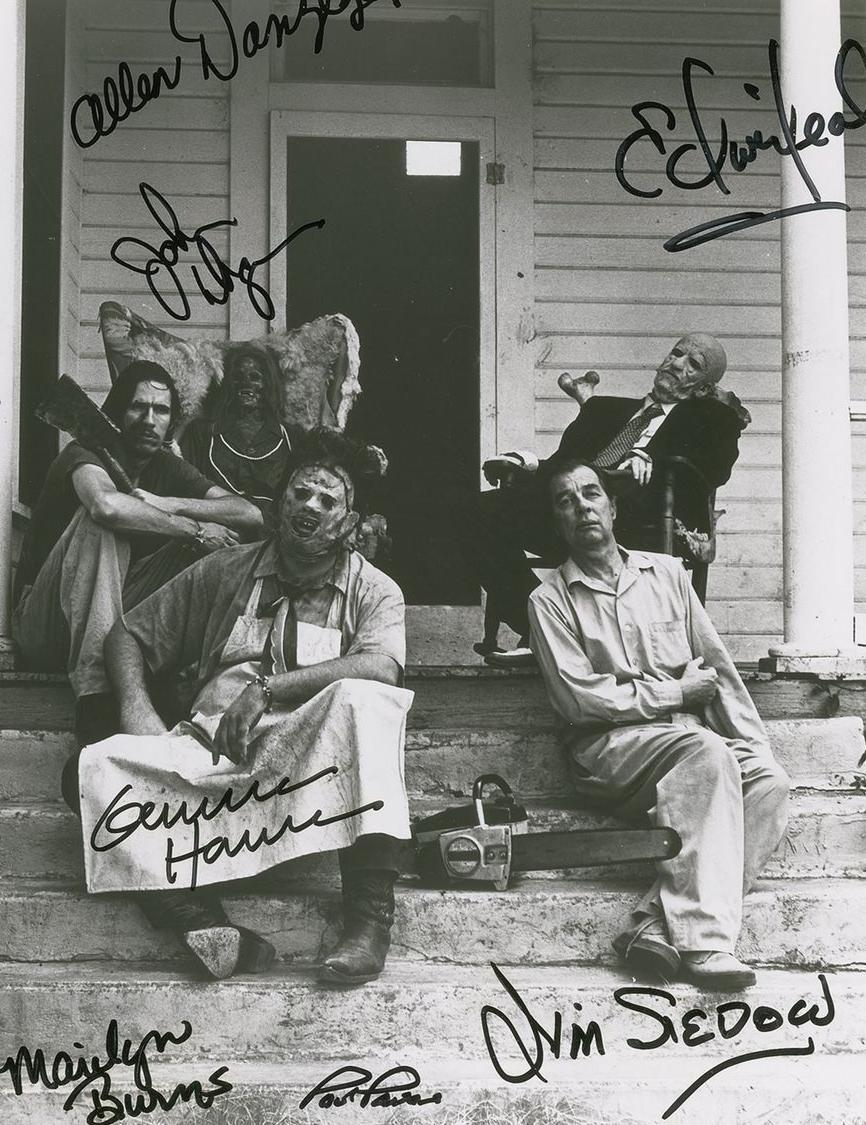

Robert A. Burns, an Art Director, signed Texas Chainsaw Massacre photos.

TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE: THE SHOCKING TRUTH

For the first time the full story behind the film which terrified the world. A documentary primarily focusing on the filming and release of the original Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

“No 3-D, no CGI, welcome to this Umami Burger of a movie. If you haven’t seen it, you will be unable to not give yourself to it. It is a very powerful experience. It transcends the genre.” —William Friedkin

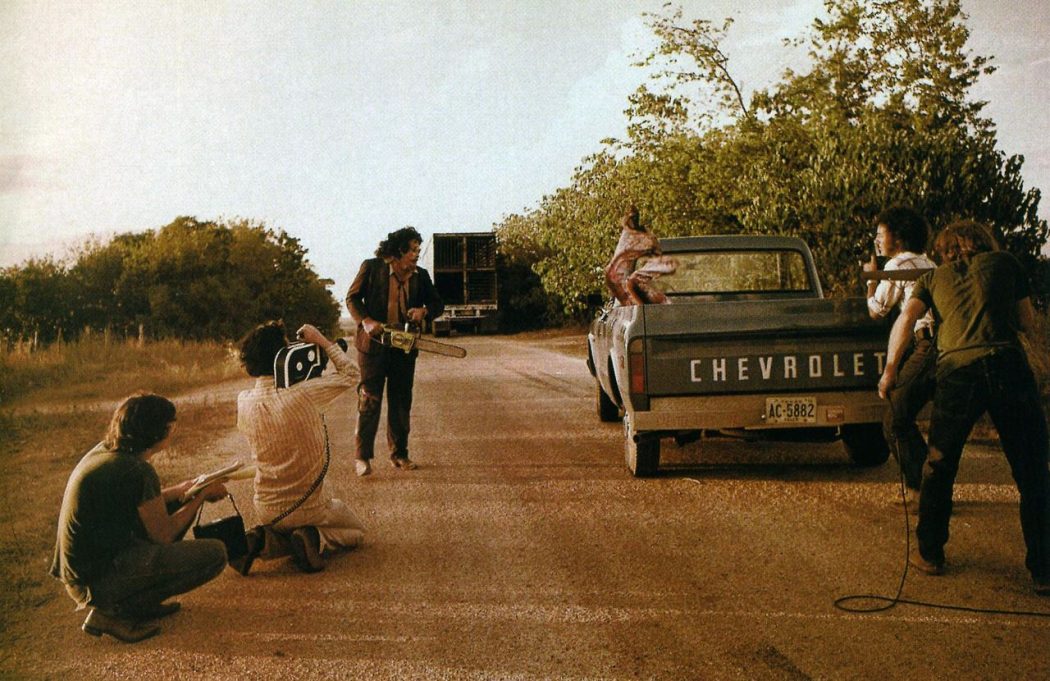

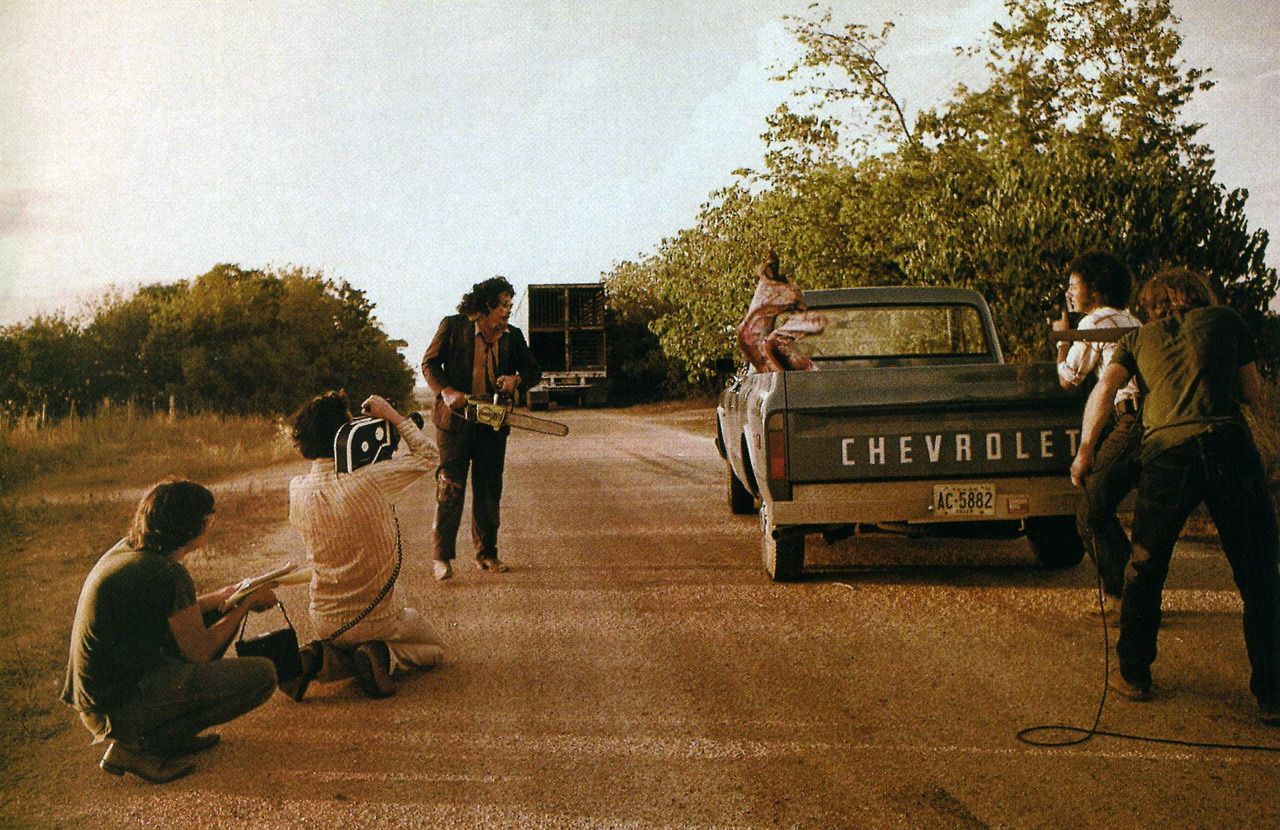

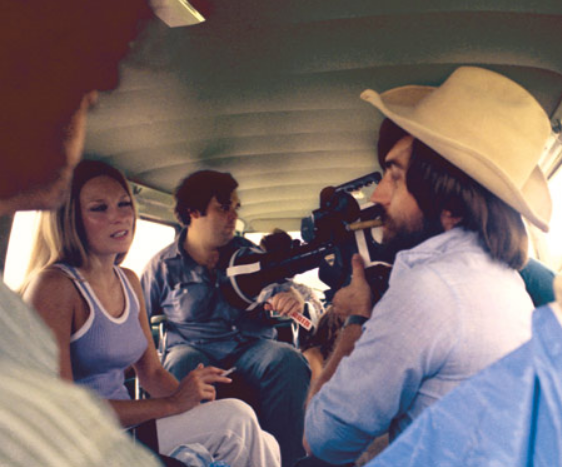

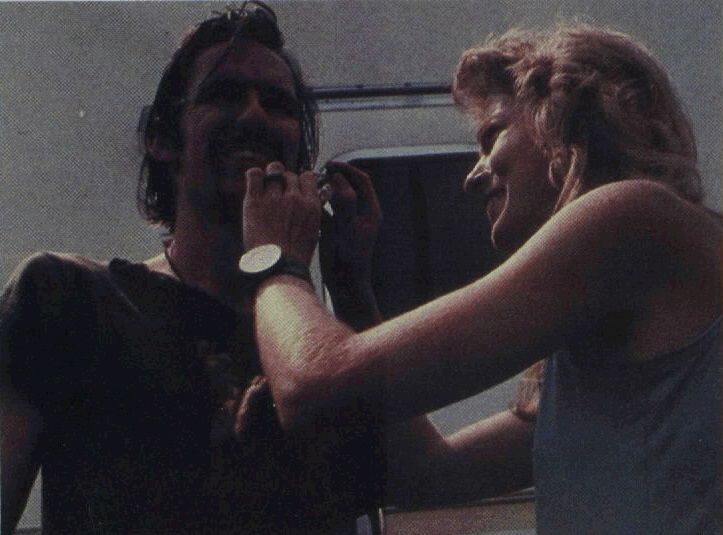

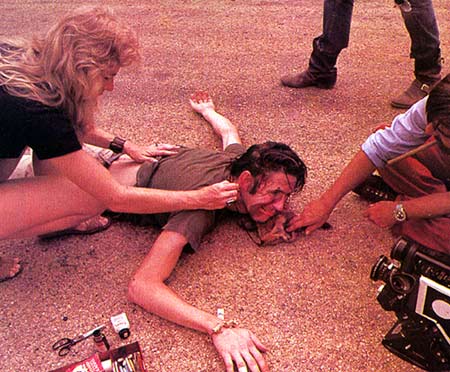

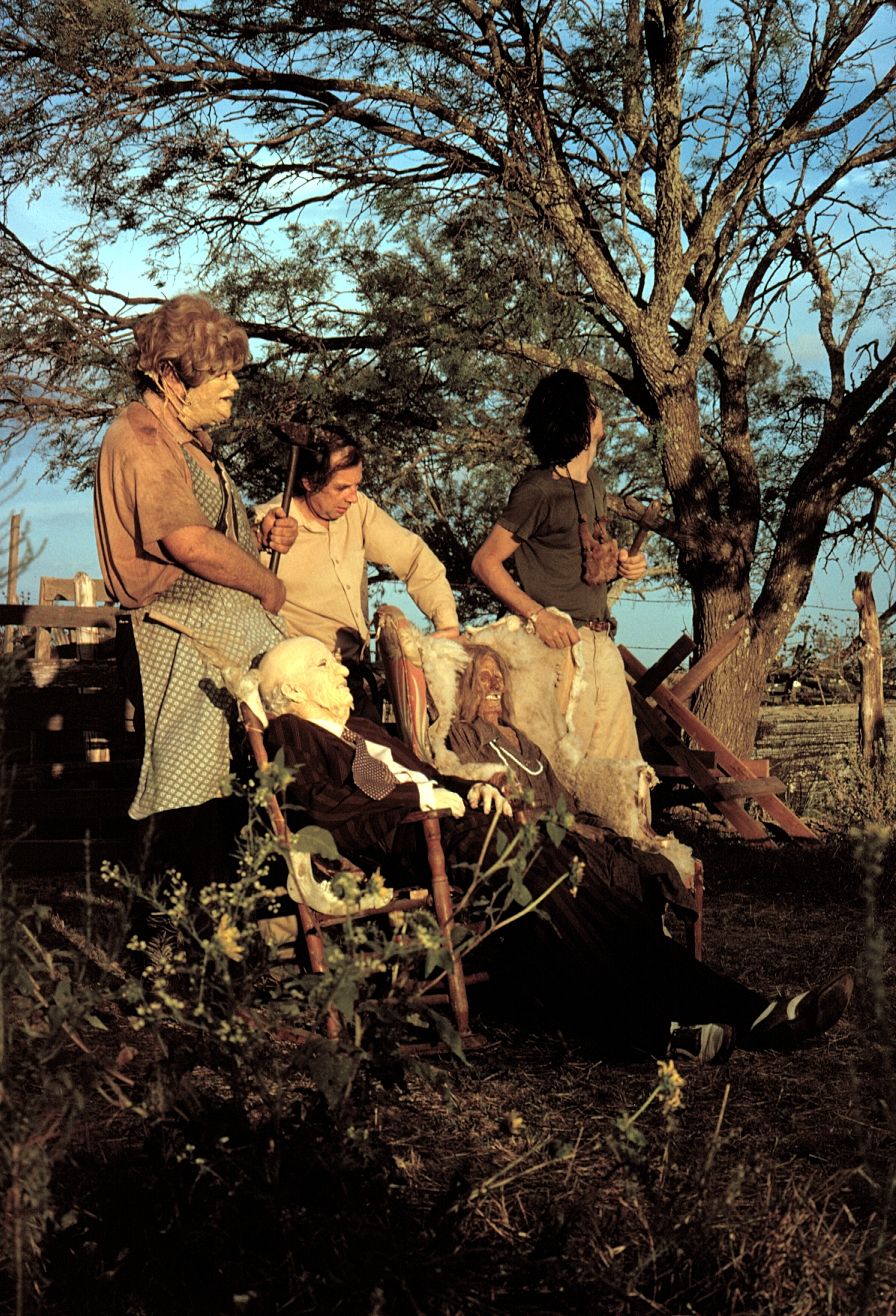

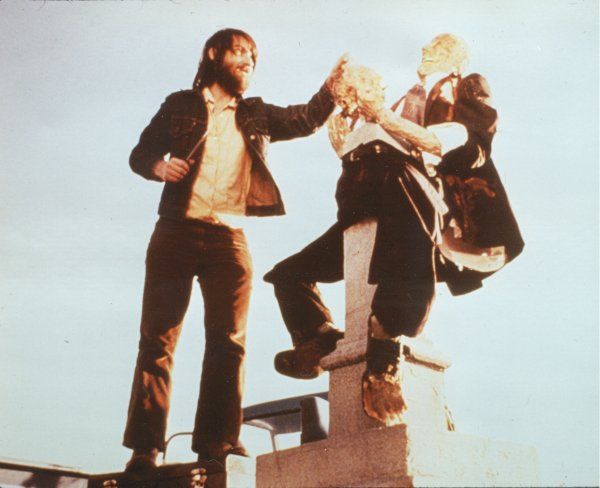

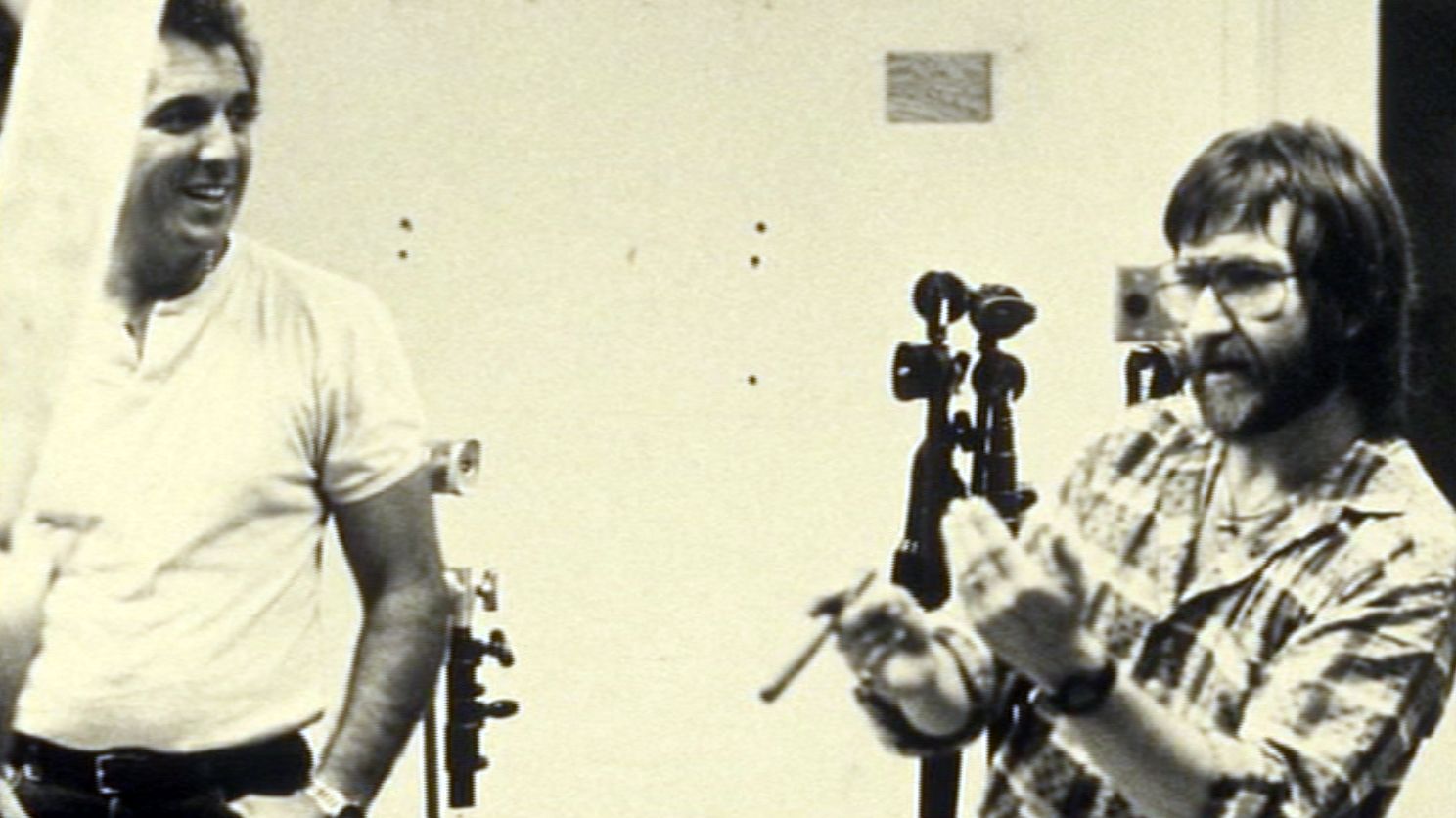

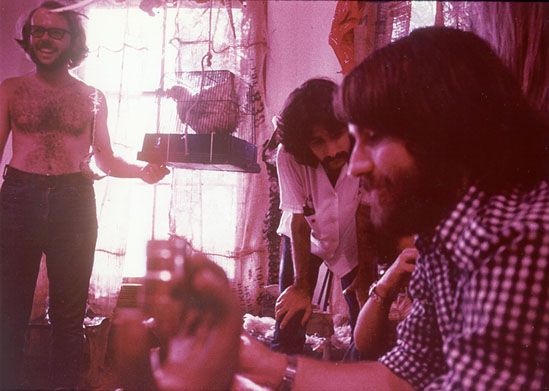

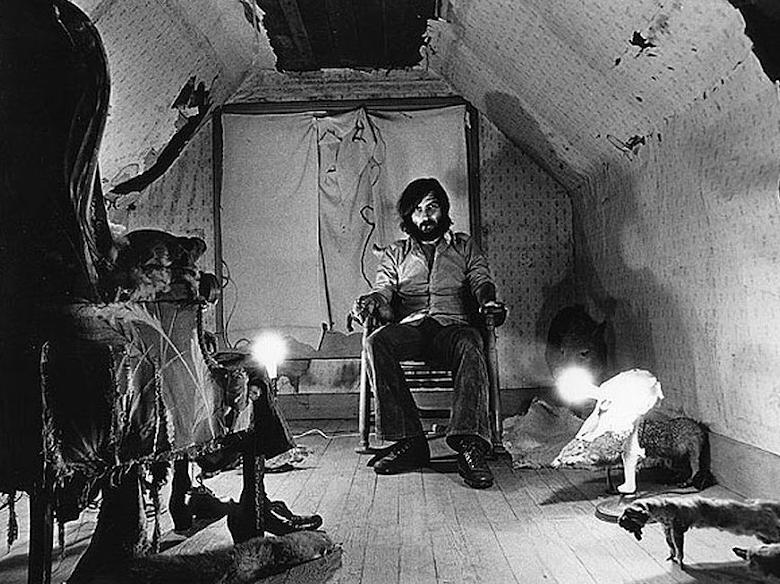

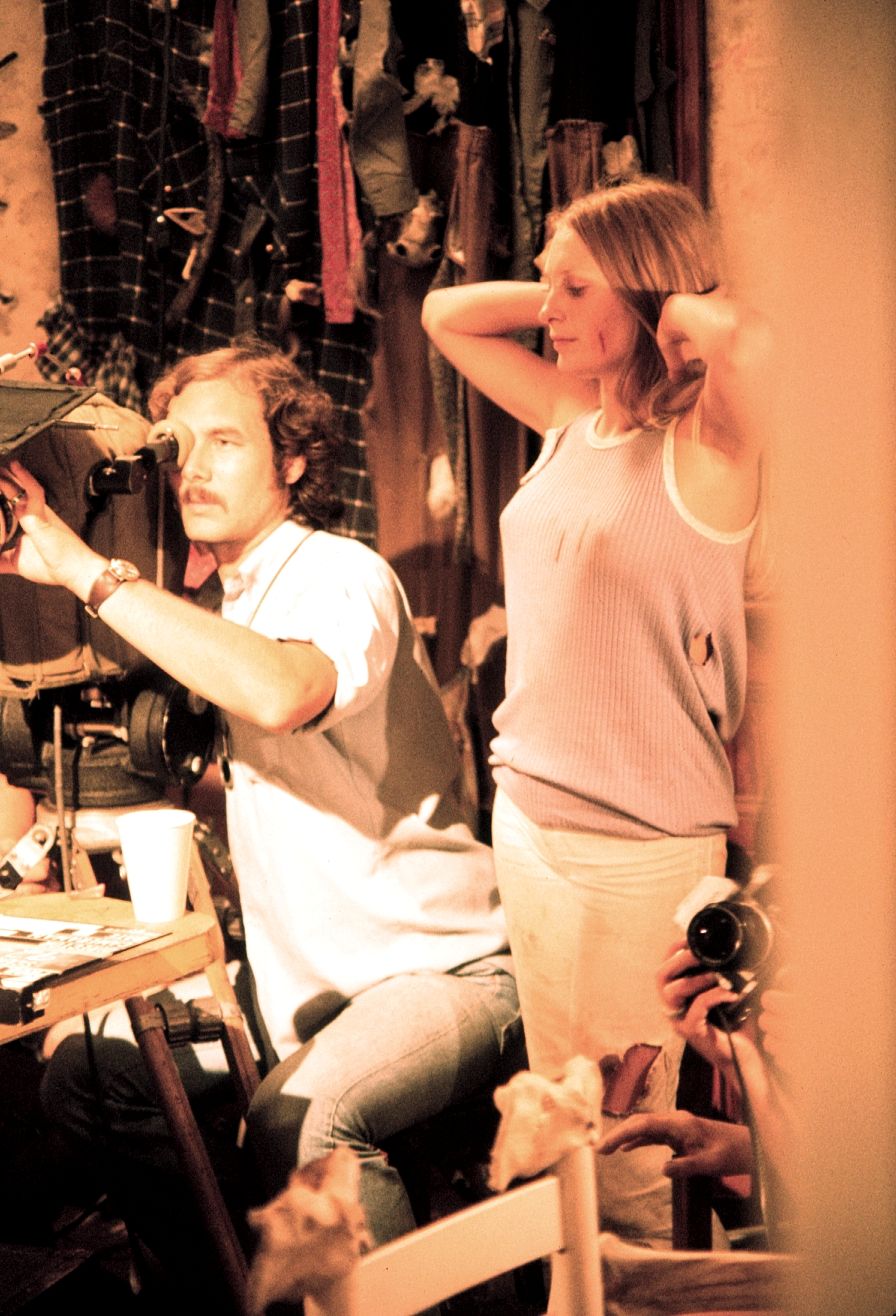

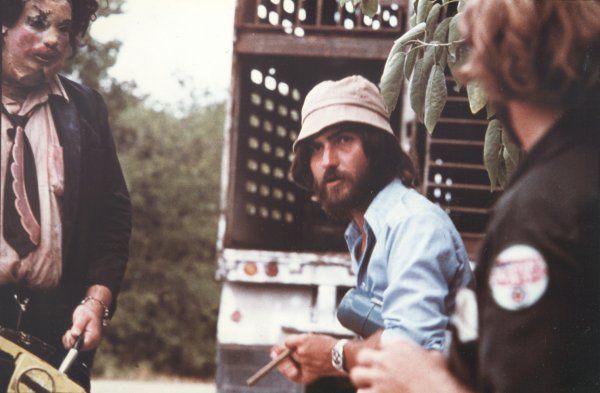

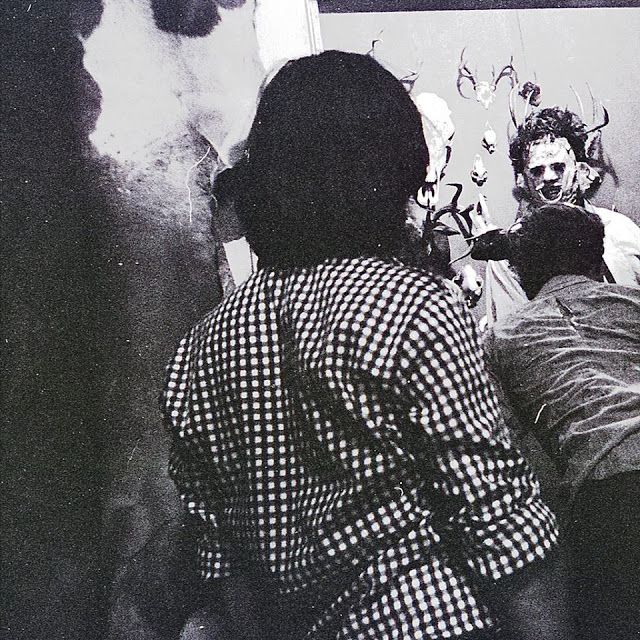

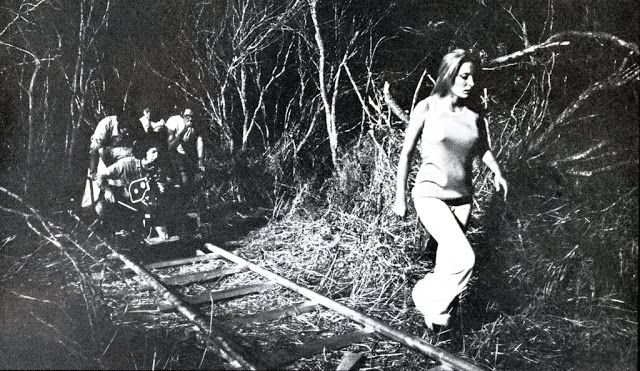

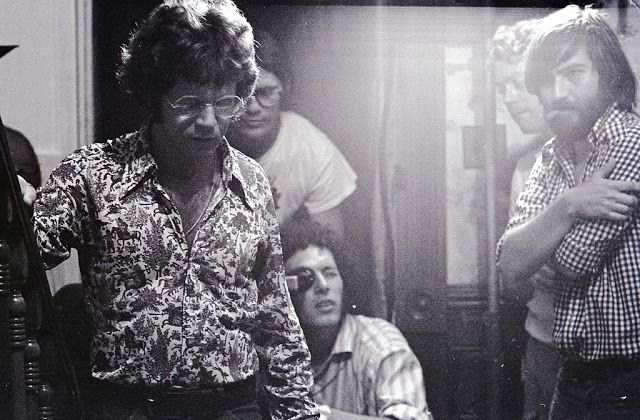

Here’s another fascinating compilation of photographs taken behind-the-scenes during production of Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre © Vortex/Bryanston Distributing Company/Photofest. Intended for editorial use only. All material for educational and noncommercial purposes only.

We’re running out of money and patience with being underfunded. If you find Cinephilia & Beyond useful and inspiring, please consider making a small donation. Your generosity preserves film knowledge for future generations. To donate, please visit our donation page, or click on the icon below:

Get Cinephilia & Beyond in your inbox by signing in

[newsletter]