I’m very happy when films I’ve made are still recognized by whomever decades after they were made, but for most part you make films for a contemporary audience, the great William Friedkin recently told us in an exhilarating interview. This respected filmmaker’s statement inexplicitly concerned Sorcerer, his 1977 existential thriller that had the misfortune of hitting theaters at the same time as George Lucas’ Star Wars, a film that Friedkin claims changed everything and a point in Hollywood history that many critics and analysts see as a starting point of the new blockbuster era, which marked the end of the New Hollywood cinema movement. Initially conceived as a small film with the budget of mere 2,5 million dollars, developed as a stepping stone for Friedkin’s next big project, The Devil’s Triangle, Sorcerer grew into a 22-million-dollar beast that failed to justify its expenses at the box office. History has been far more kind to the film that Friedkin considers his most personal one, as Sorcerer is nowadays hailed as a true masterpiece and one of indisputable classics of a dying era. A reimagination of Henri-Georges Clouzot’s 1953 The Wages of Fear, Sorcerer features the story of four characters in charge of transporting two trucks full of nitroglycerin to a remote oil well. These people are difficult to sympathize with: portrayed as neither heroes nor villains, they are flawed individuals in a dire situation over which they have literally no control. Their lives are ruled by chance and fate. It is the latter which the puzzling title of the film refers to: the evil wizard playing with people as helpless puppets is actually fate, as Friedkin nicely put it, waiting around the corner to kick you in the ass. Even more significantly, the main theme is easily related to the political situation of the seventies, as well as it’s hardly preposterous to link it to the contemporary barrel of gunpowder the world has turned into: the characters, who have hardly anything in common, are forced to collaborate, overcome their differences and, concerned with the common good, repress their primary selfish preoccupation with their own well-being. A simple, yes, but beautiful and highly effective metaphor Friedkin manages to employ without ever leaving the impression of artificial moralizing or high-horse didacticism.

Written by Walon Green, whose work on The Wild Bunch Friedkin allegedly admired, based on Georges Arnaud’s ‘Le Salaire de la peur,’ shot magnificently by John M. Stephens and his predecessor Dick Bush, abounding in fantastic scenery and breathtaking landscapes, greatly enriched by Tangerine Dream’s electronic score, and presenting a rock solid performance by Roy Scheider, Sorcerer is a masterful presentation of impressive filmmaking abilities that turned William Friedkin in one of the most cherished auteurs of the last half a century. “Life is actually a beautiful gift, but people regard it not as something that is vulnerable, but as something that they take for granted. The major powers in the world just keep threatening each other, attacking each other, and there’s going to come a point where there’s enough nuclear proliferation to destroy the world,” Friedkin told us. Cautionary tales have seldom taken such an amazing artistic form.

A monumentally important screenplay. Dear every screenwriter/filmmaker, read Walon Green’s screenplay for Sorcerer. Based on the novel ‘Le Salaire de la peur’ by Georges Arnaud [PDF]. (NOTE: For educational and research purposes only). Newly remastered Blu-ray under the supervision of William Friedkin is available at Amazon and other online retailers. Absolutely our highest recommendation.

Loading...

Loading...

“I had seen The Wages of Fear and I thought it was a great film. It was really a theme about brotherhood. You had four guys, total strangers to each other, hated each other, and had to cooperate with one another or die. Make a last stand together or die. And I thought that this was really a metaphor for the world, for all the various nations of people who hated each other, yet had to find a way to live together, or perish. This theme should be continuously revived and presented to an audience. So I didn’t want to remake Wages. I wanted to take that theme and do a new version with my own kind of spin on it that was based on the Georges Arnaud novel. I just thought it was another interpretation of a great classic.” —William Friedkin, Hollywood Flashback interview, 1997

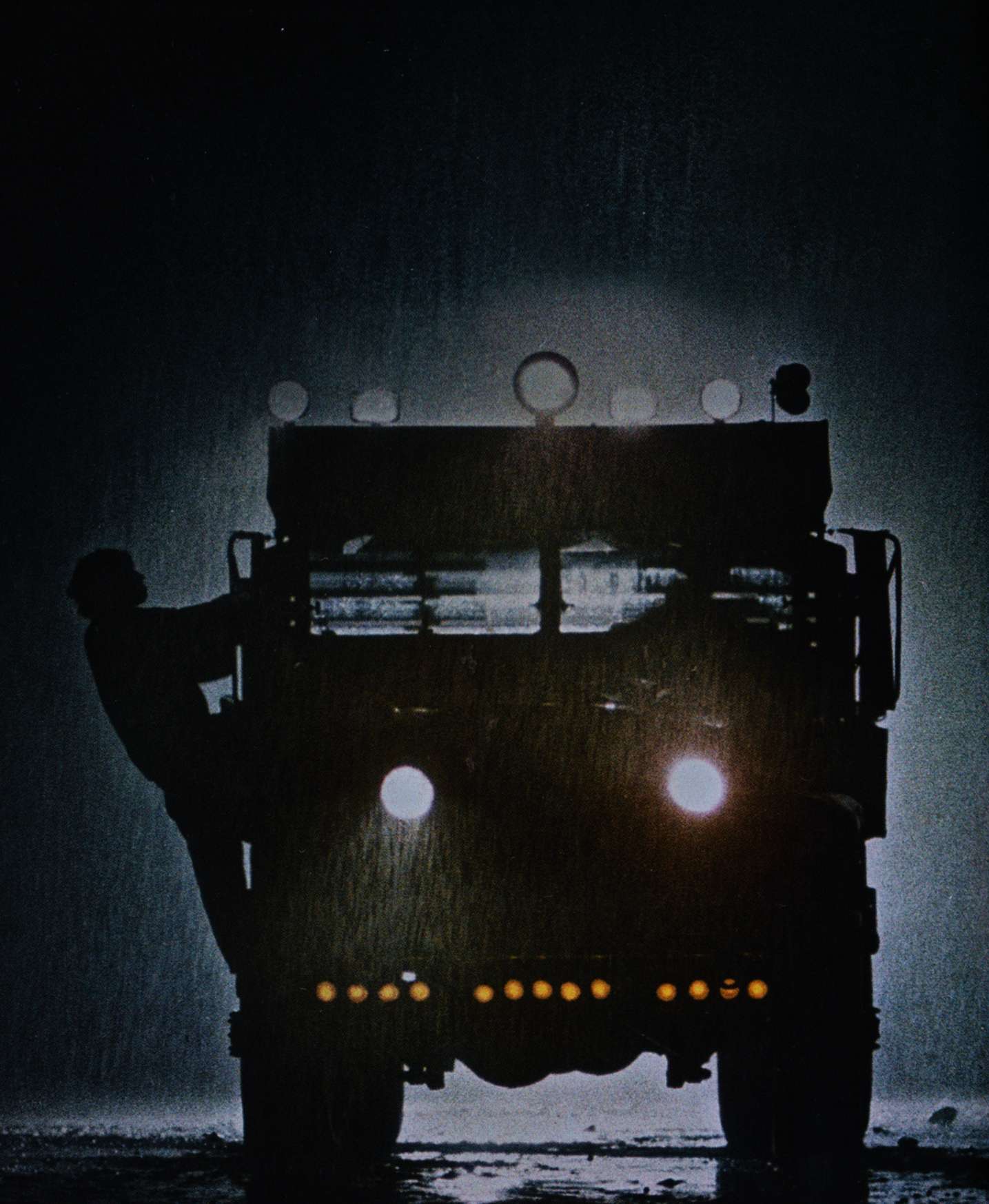

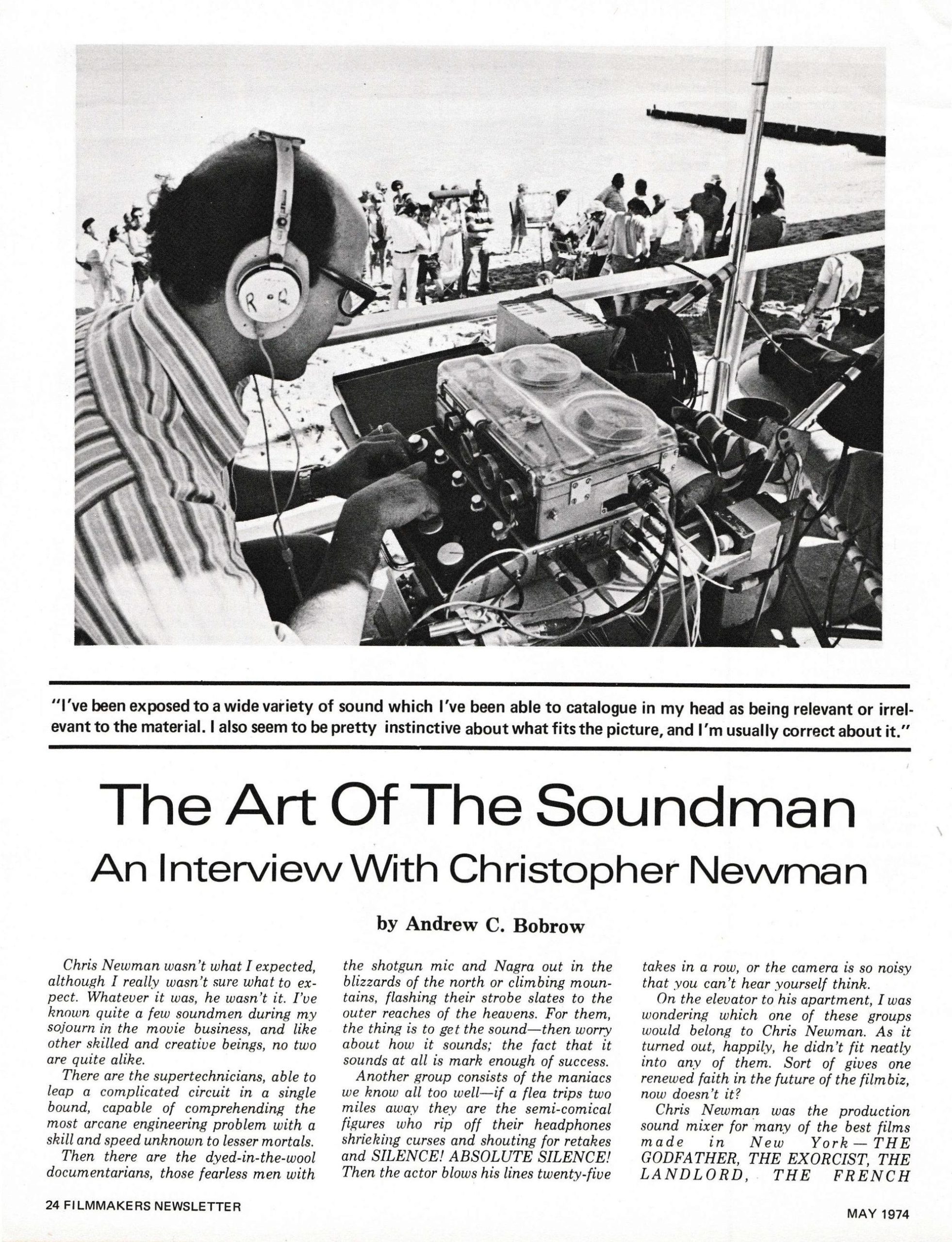

Selected by Friedkin as his personal favorite, Sorcerer tells the story of four unfortunate men (Roy Scheider, Bruno Cremer, Francisco Rabal and Amidou) from different parts of the globe, forced by their various misfortunes to work in a dangerous oil-drilling operation in South America. After an industrial accident, these outcasts are given the opportunity to earn enough money to escape this situation if they undertake a perilous mission of transporting crates of unstable high-explosives through 200 miles of treacherous jungle terrain in two ancient trucks. The film has been lauded by critics as an overlooked masterpiece and was nominated for an Academy Award for best sound. Following an introduction by DGA Special Projects Committee Chair Jeremy Kagan, Friedkin spoke about the film he has called the most difficult movie he ever made; discusses the ambiguous moral situation in Sorcerer, challenging audiences to root for the main characters with villainous backgrounds; explains his intentions behind using flash-frame cutaways towards the end; and traces his path from making The Exorcist to Sorcerer, and the new theme he wanted to explore —An Evening with Director William Friedkin

MASTER CLASS DE WILLIAM FRIEDKIN : À PROPOS DE SORCERER

A few months after its world premiere at the Venice Film Festival, the restored version of William Friedkin’s resurrected masterpiece Sorcerer was screened in Paris at La Cinémathèque Française as the opening film of the 2nd edition of ‘Toute la Mémoire du Monde,’ an international festival devoted to recently restored films. Among the topics discussed during the masterclass, the director tells how and why Steve McQueen, Lino Ventura and Marcello Mastroianni got in and out of the project, how Star Wars ruined the potential success of Sorcerer, how difficult the shooting was (“It was life threatening; almost everyone on the crew got sick. I myself got malaria.”), how demanding he is as a director (“Come on! Do I seem tyrannical?”), how he sued the studios to get his film back (“I did not sue them for money. I will never make a penny out of this picture.”) and how he worked on the restoration of the movie (“It took me about six months. Six months of my own time, and I lovingly restored every single frame of that picture…”). —William Friedkin’s Sorcerer Celebrated In Paris Before Its Worldwide Release

“I wanted to make an action-adventure film that had a more profound meaning, like the mystery of fate, and that’s what Sorcerer’s about. It’s about the mystery of fate, and purgatory, and redemption, and in contemporary terms. I felt that the story embodied in The Wages Of Fear, the French novel and the film, fit that template very clearly. I wanted to do a version of it, in the same way that if someone does a version of Hamlet on the stage, it’s not a remake, it’s a new production, a new interpretation. And that’s how I did it: I changed all the characters, I changed all the incidents, but kept the spine of the original framework of the story, because I thought it was timeless. I had no interest in doing a remake or a shot-for-shot or anything like that, but I love the premise, the essential premise of four strangers who mostly didn’t like one another, delivering a load of dynamite, and they either had to cooperate or die. And that seemed to me like a metaphor for the world situation—even more so today.” —William Friedkin on Sorcerer, his career, and fate

A rare 8mm footage behind-the-scenes footage of William Friedkin’s Sorcerer, courtesy of Edkfilms.

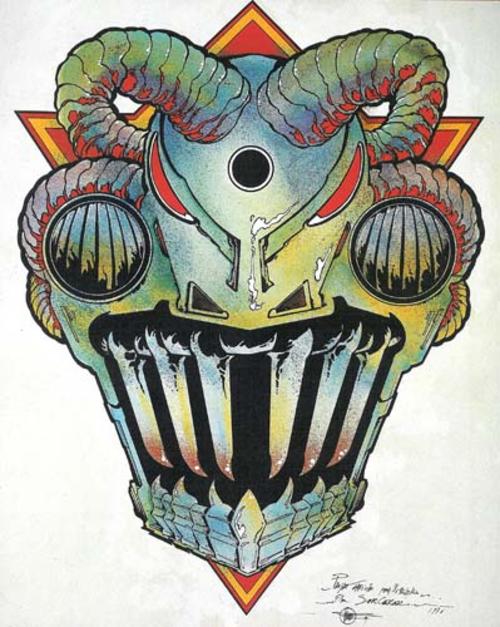

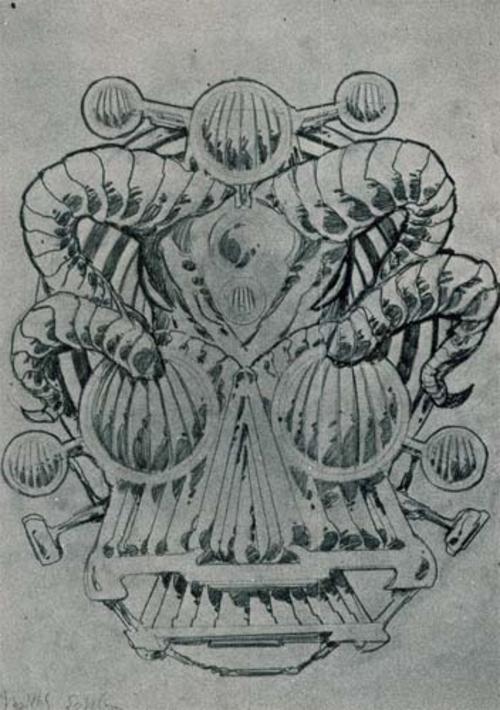

At some point in pre-production for Sorcerer, William Friedkin had the French comic illustrator Philippe Druillet do some concept sketches for the trucks. What he came up with hardly looks like something you’d see in a film committed to authenticity and realism, but it’s cool stuff. —Toby Roan, The Sorcerer Blog

Probably the oddest thing about the Sorcerer/Druillet connection is that the commercial failure of the film in 1977 has often been laid at the door of Star Wars, the advent of George Lucas’s dismal saga being regarded, with some justification, as the opening of the gate to the barbarian hordes. (Friedkin’s film might also have fared better had it not been titled as though it were an Exorcist sequel.) The irony here is that George Lucas happened to be a big Druillet enthusiast, although there’s little evidence of this in his films; in addition to writing an appreciation for ‘Les Univers de Druillet’ in 2003, he also commissioned Druillet to create a one-off piece of Star Wars art in the late 70s. Knowing this it’s tempting to imagine Lucas creating a very different kind of science-fiction film in 1977, one with some Continental weirdness at its core. But when the world has already been deprived of Jodorowsky’s Dune it’s best not to dwell too much on might-have-beens. —John Coulthart

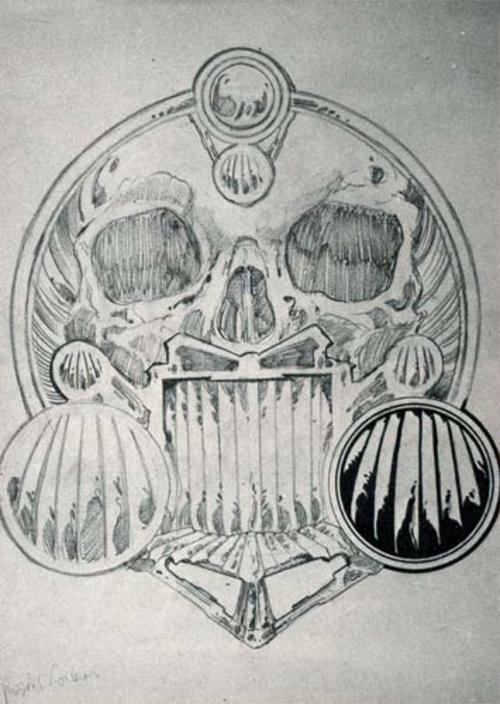

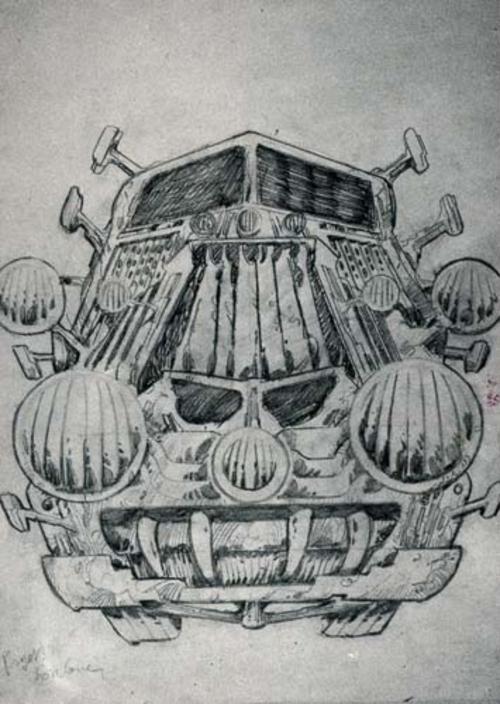

JOHN BOX’S SKETCHES

Here are three of John Box’s sketches of the trucks from Sorcerer. Fascinating stuff. Courtesy of Toby Roan’s The Sorcerer Blog.

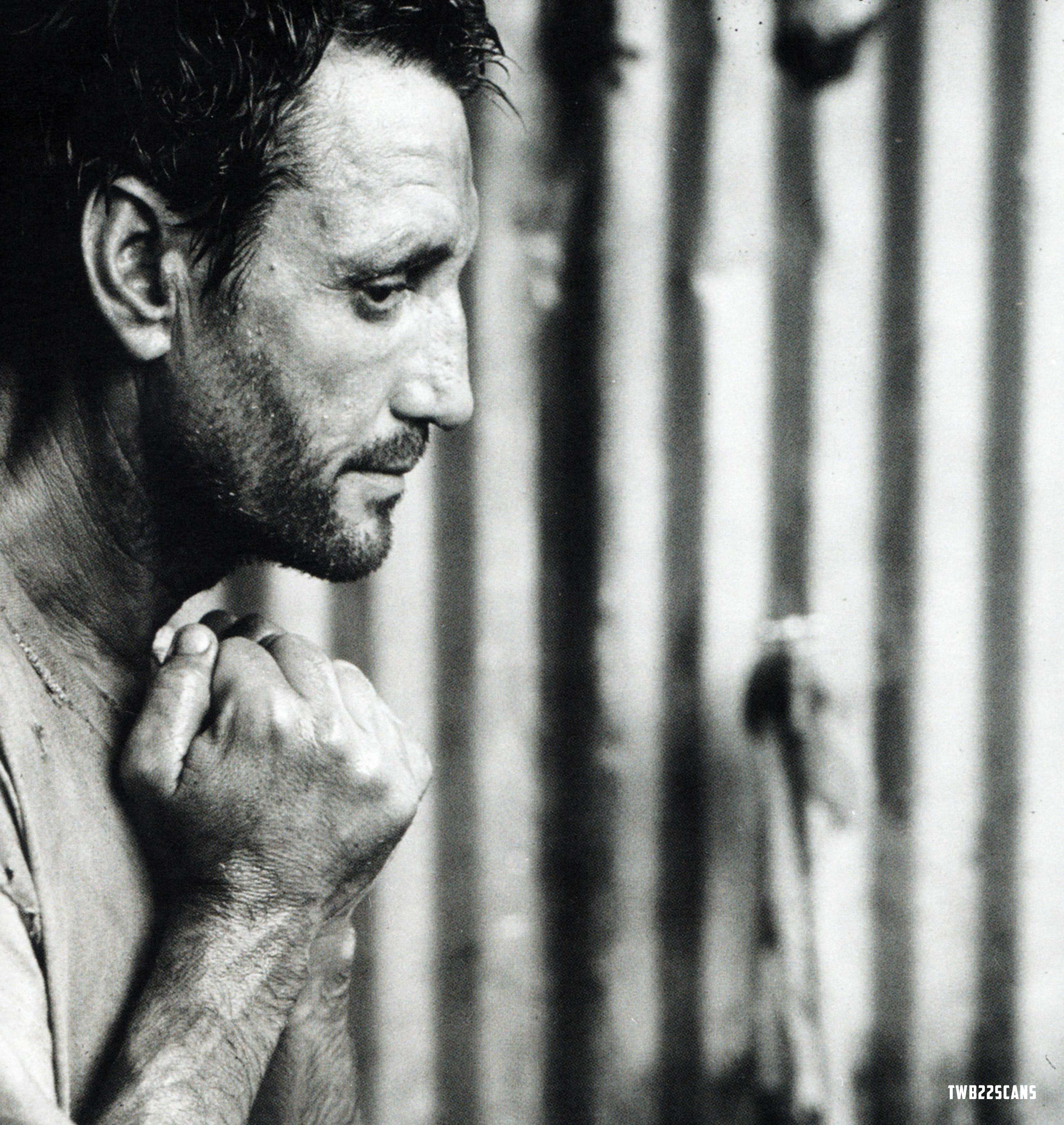

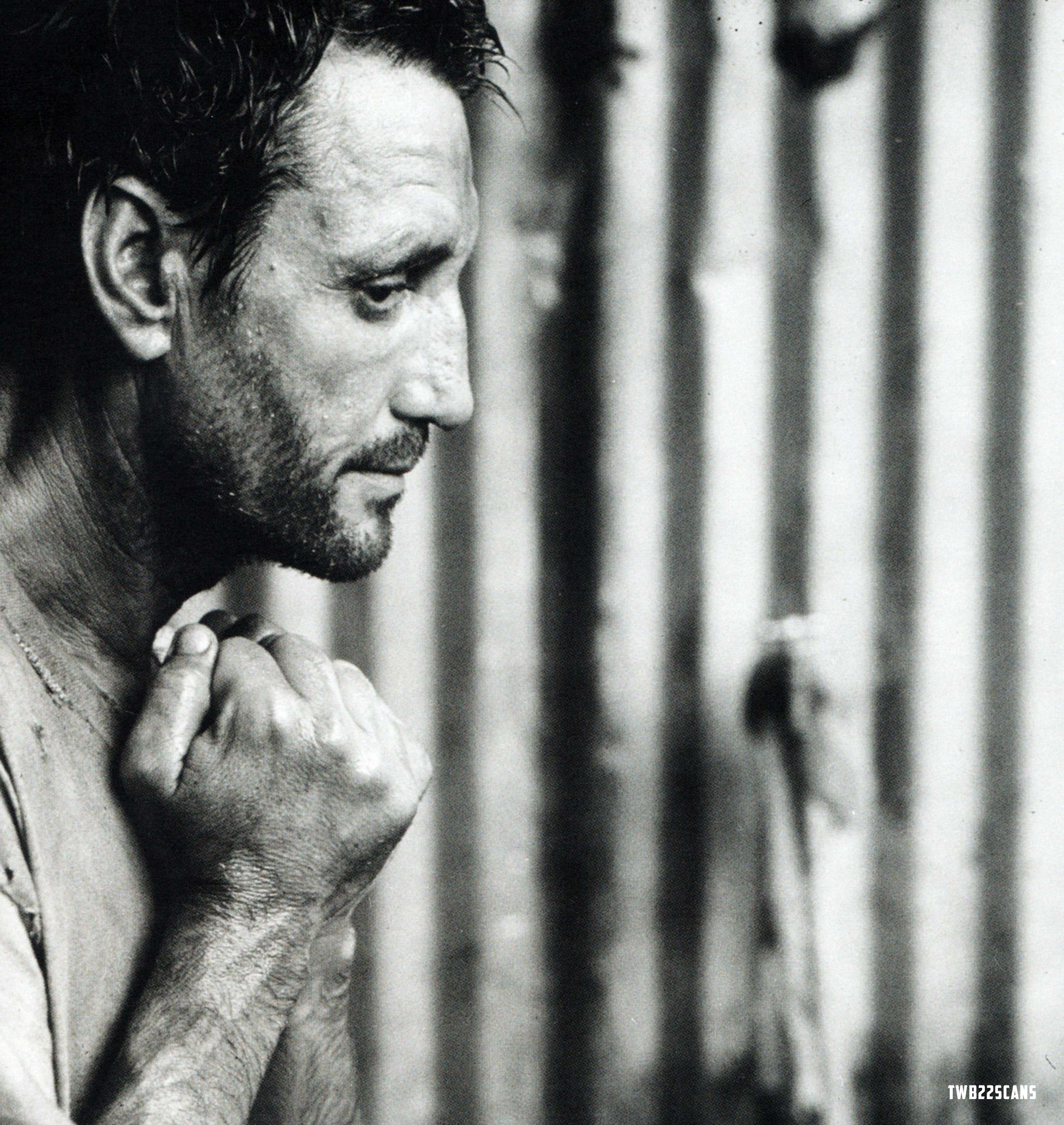

“What I did in Sorcerer makes Jaws look like a picnic… The stuntmen complained because the principals were doing all the stunts, but that’s the way Billy Friedkin makes movies. The most dangerous scene I’ve ever shot was the one where we were driving across a rope suspension bridge in a horrible storm and we kept swaying back and forth, back and forth. What the audience will see on that screen is what really happened.” —Roy Scheider, Sorcerer Star, Talks Of Thrillers, January 21, 1977

“I was rehearsing to stay alive… When we got to the Dominican Republic, I appreciated all that practice back in the States. Billy’s approach to Sorcerer ruled out rear-projection or trick photography. The actors, the vehicles and the terrain were too closely integrated into the composition of each shot. So what you see in the film is exactly what happened. When I take a mountain road on two wheels, on a road with potholes the size of shell craters, that’s the way it was. No one but Billy Friedkin could have persuaded me to take the insane chances I did. But when it was over and I looked at the rough footage I knew it was worth it.” —Roy Scheider

“We finally got so deep in the jungle that the crew had to build its own roads. Then we chewed them up with the trucks. Years from now, some geographer will have one heck of a time trying to figure out who built all those roads going nowhere… and why.” —Roy Scheider, The Henderson Home News, September 29, 1977

“In the ’70s I only made, like, three films, and if we talk about them—The French Connection, The Exorcist, Sorcerer and, later, Cruising. That had Al Pacino. It could’ve been De Niro. I liked his work in the ’70s very much, but I only made those few films and they took up every day of my life! I would love to have worked with De Niro back then, without a doubt. It’s not simply that you like an actor; you have to have a role for that particular actor. And I simply didn’t do that many films. The guy I really wanted to work with other than anyone was Steve McQueen, and I almost did on Sorcerer, but for a variety of reasons we couldn’t get together. The script was written for him.” —William Friedkin

“Walon Green wrote the Sorcerer screenplay for Steve McQueen to play the Scheider role. We sent it to Steve and he called me and said, this is the best script I’ve ever read. I love this picture. Then, he said, there are a couple of things I need you to do for me. I know you want to go out to some jungle and shoot it and I can’t do that because I just married Ali McGraw and she has a career. Can you write a part in there for her so she can be with me when I’m shooting this? I said Steve, you just told me it was the best script you ever read. There’s no major role for a woman in there. He said, okay, I get it. Then why don’t you make her a co-producer? I said Steve, I’m not going to do that, I don’t believe in that sh*t. And I certainly don’t want to schmuck bait your wife and call her a producer because she’s not going to be a producer on the film. And he then said okay I understand that, then let’s make it all in America. I said, Steve I’ve found the locations and I’m committed to them. I don’t want to do it in America. Because of those three reasons, he decided to pass.

I’ll admit something. If that came up today, I would have done anything he wanted. I was so arrogant at that time. I thought I was the star of that film. So I didn’t think that a close-up of Steve McQueen was worth a shot of the most beautiful landscape. A close-up of McQueen was worth more. When McQueen dropped out, I lost Marcello Mastroianni and Lino Ventura, who were big European stars and were known in America as well. Only my arrogance cost me that cast.” —William Friedkin, ’70s Maverick Revisits A Golden Era With Tales Of Glory And Reckless Abandon

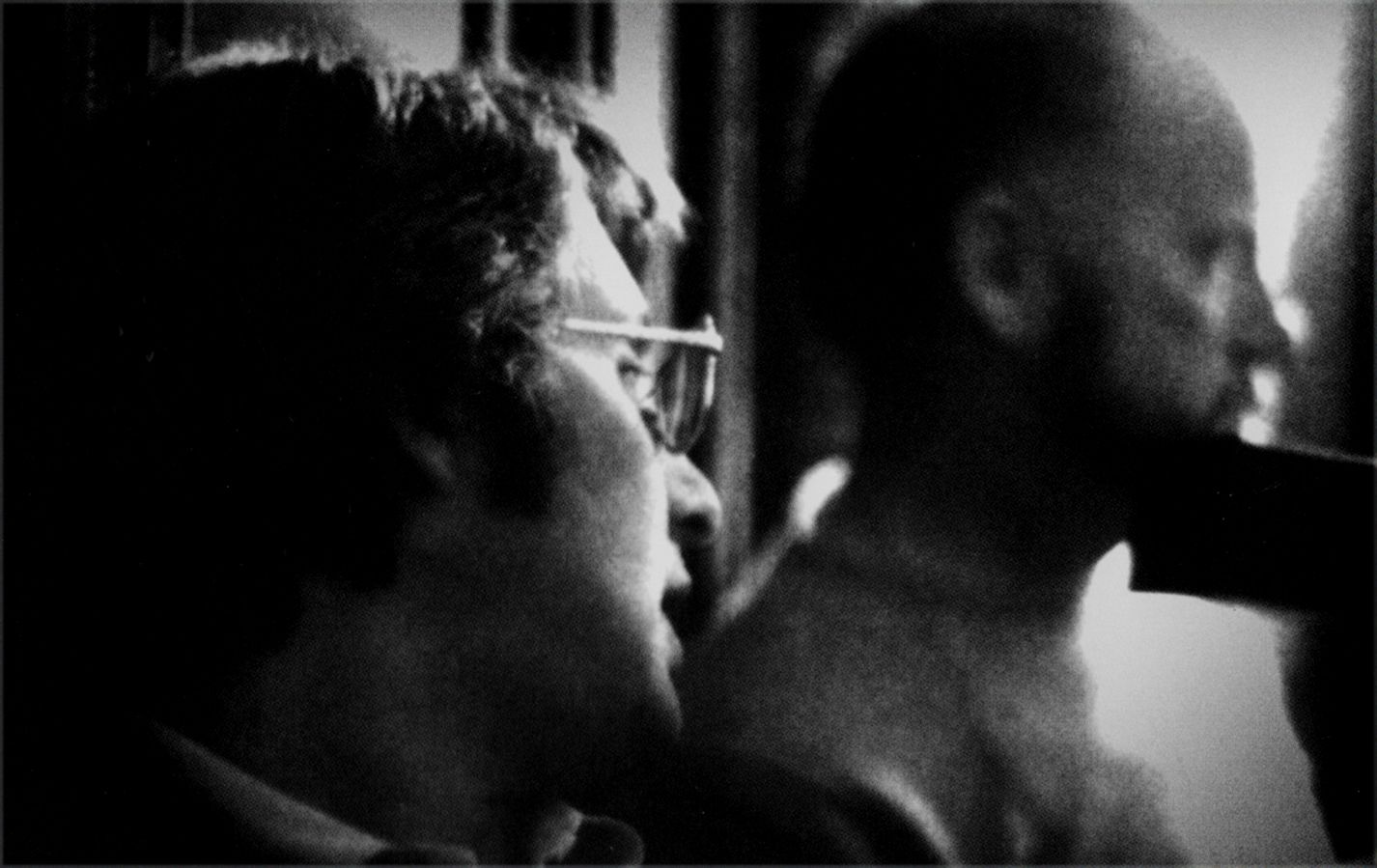

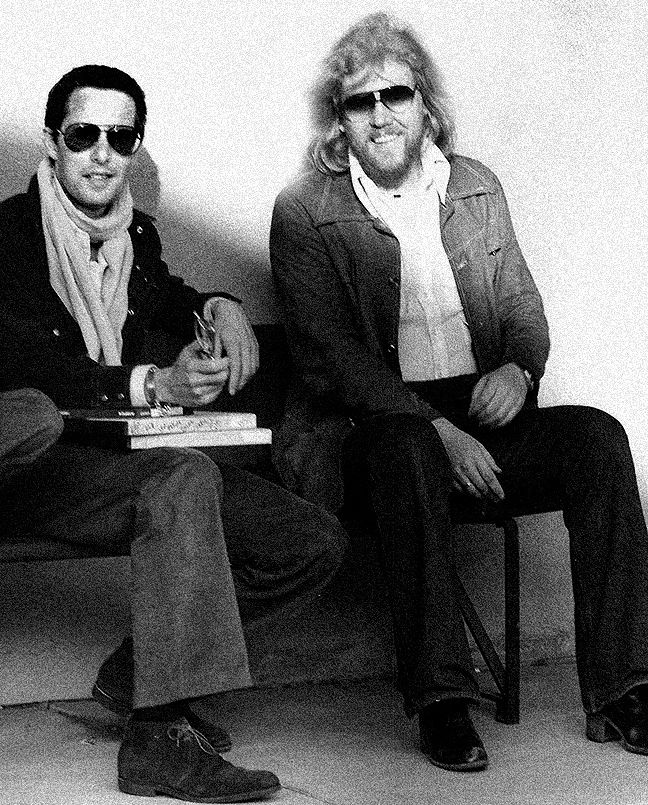

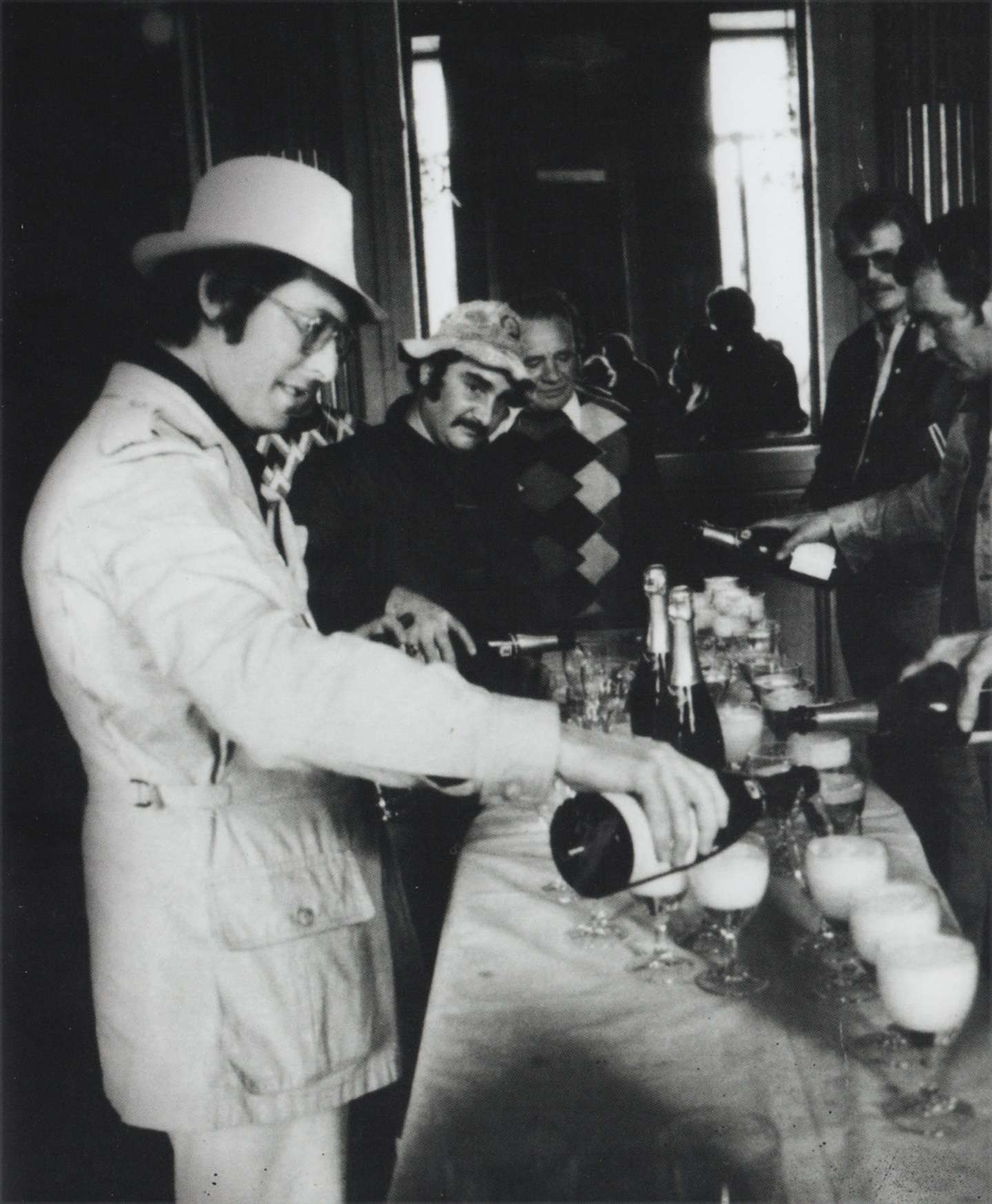

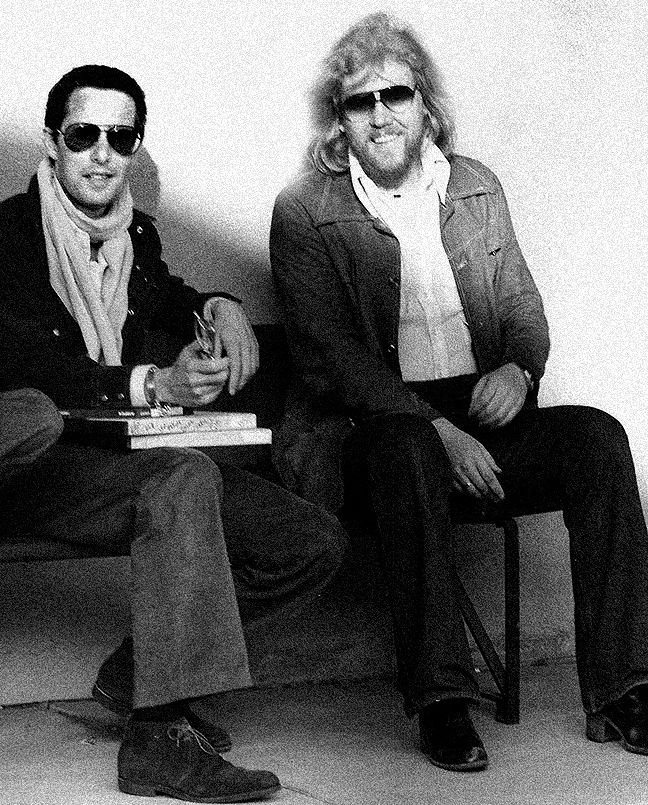

Here’s William Friedkin with Edgar Froese of Tangerine Dream. Courtesy of Toby Roan’s The Sorcerer Blog.

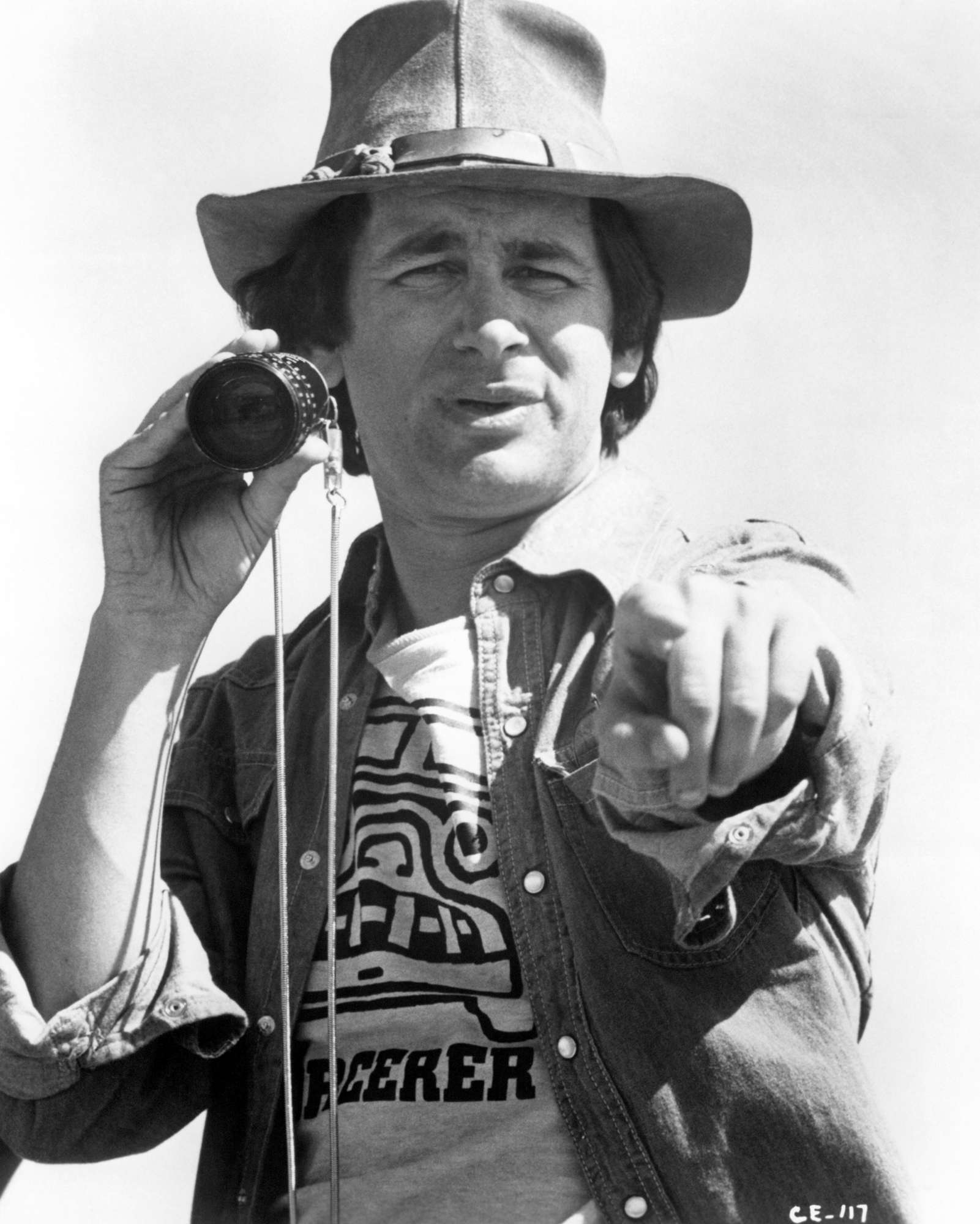

Here’s Steven Spielberg hard at work on Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), wearing a Sorcerer t-shirt.

Karlovy Vary International Film Festival presents a masterclass with William Friedkin, an outstanding figure of American filmmaking who received the Crystal Globe for Outstanding Artistic Contribution to World Cinema and presented a restored version of one of the central films of his career, Sorcerer.

Director William Friedkin is a consummate storyteller, which explains why he tells such an entertaining story of his own life, rooted in three recurring themes: faith, fate and film. Within that story, William tells Marc Maron about the making of The French Connection and The Exorcist, the failure and resurgence of his film Sorcerer, and his reasons for never wanting to do a second take.

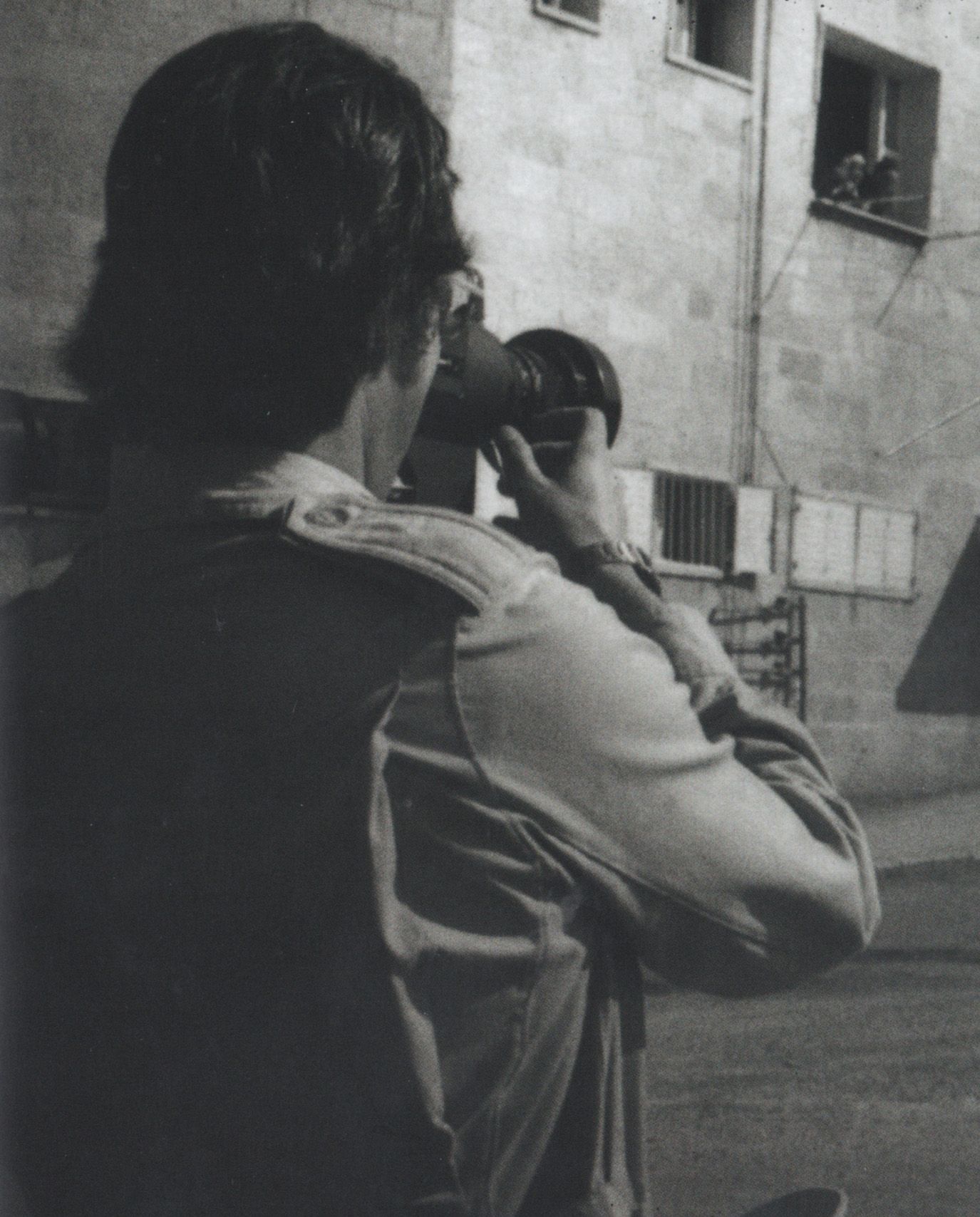

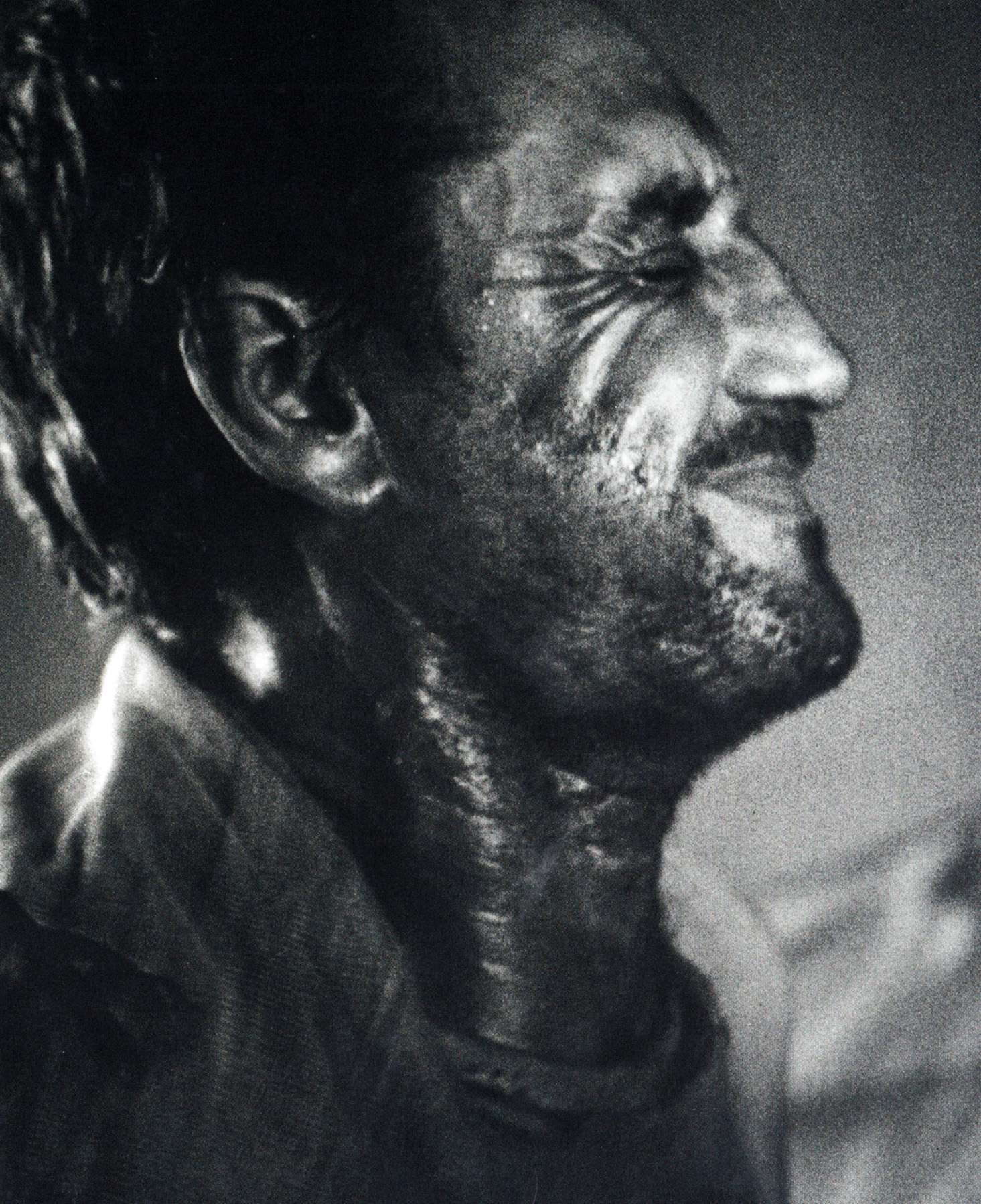

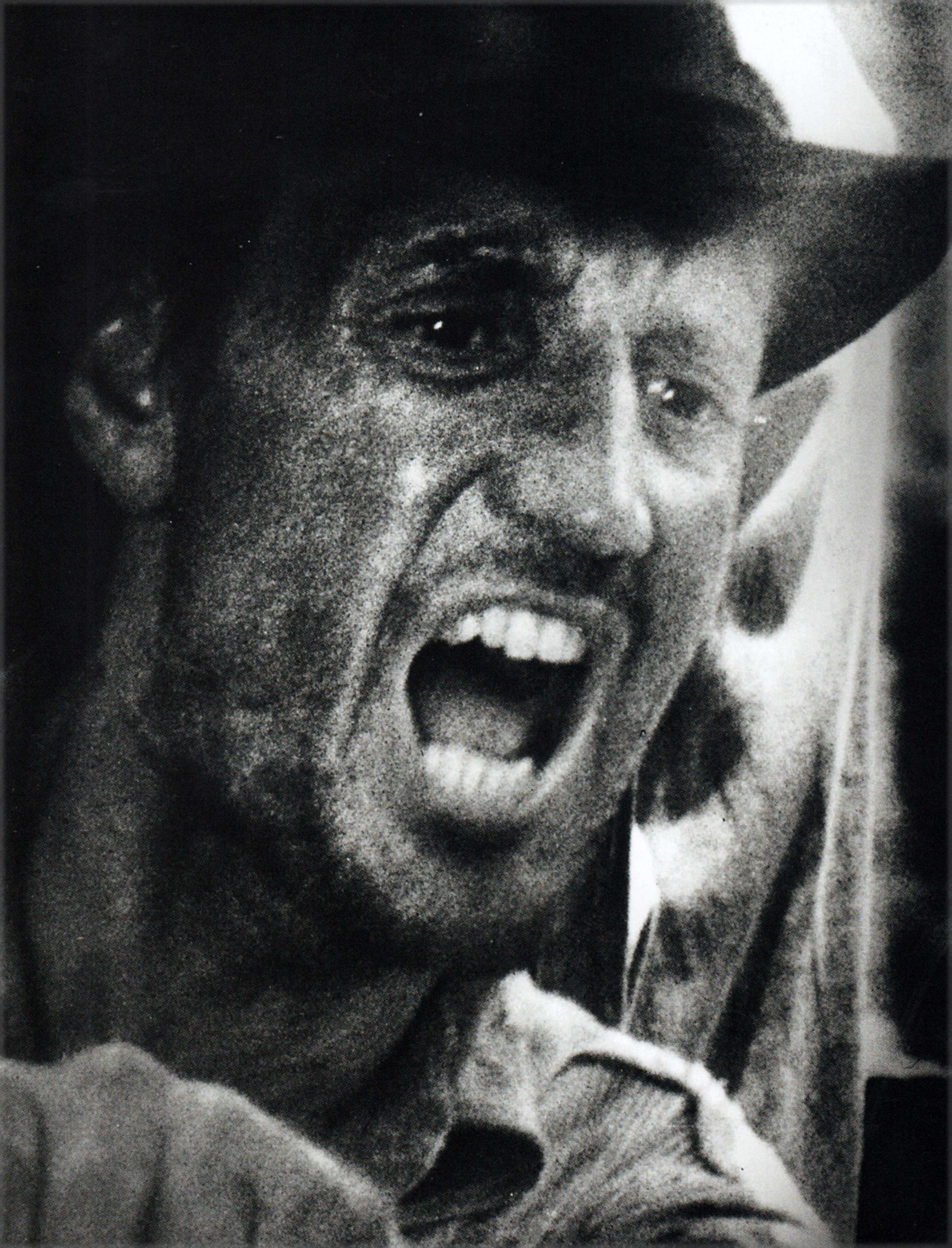

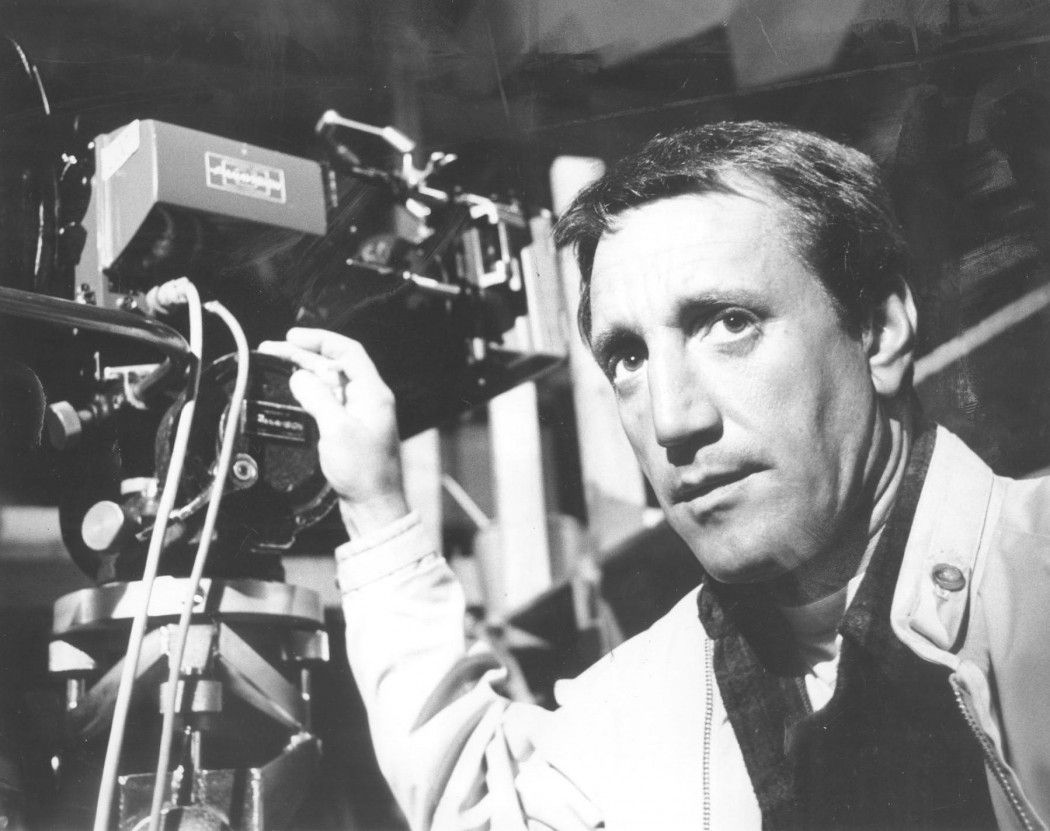

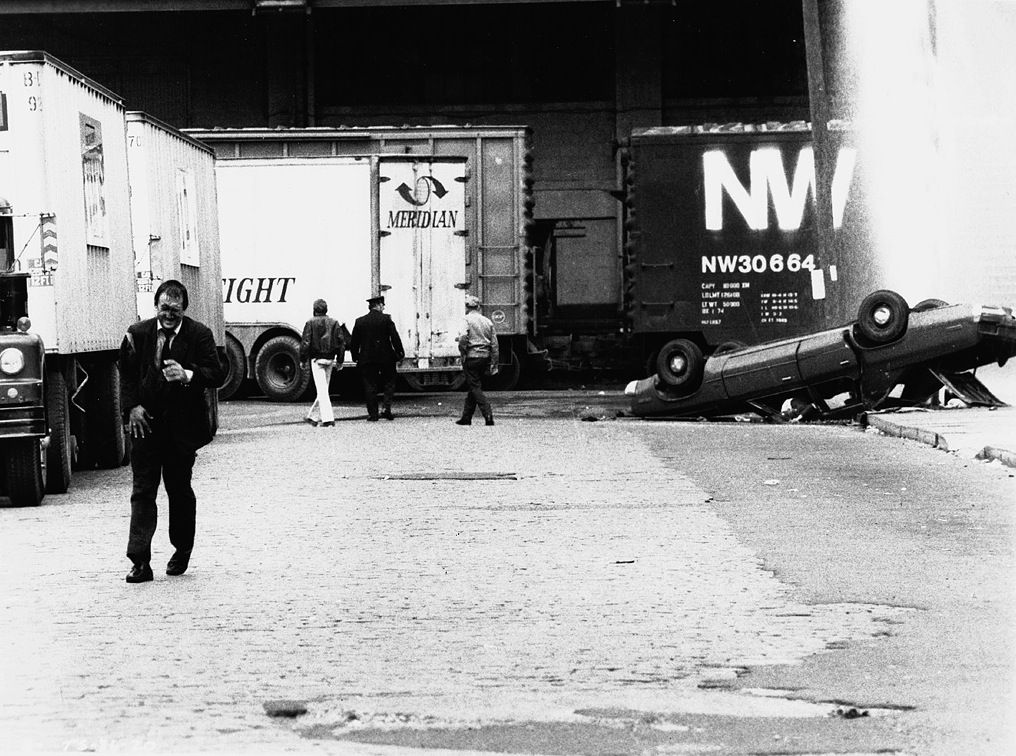

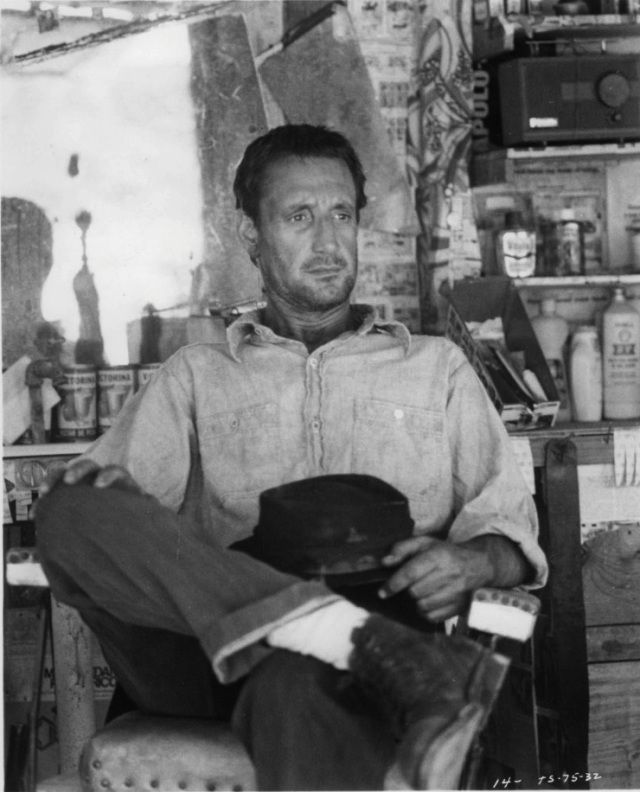

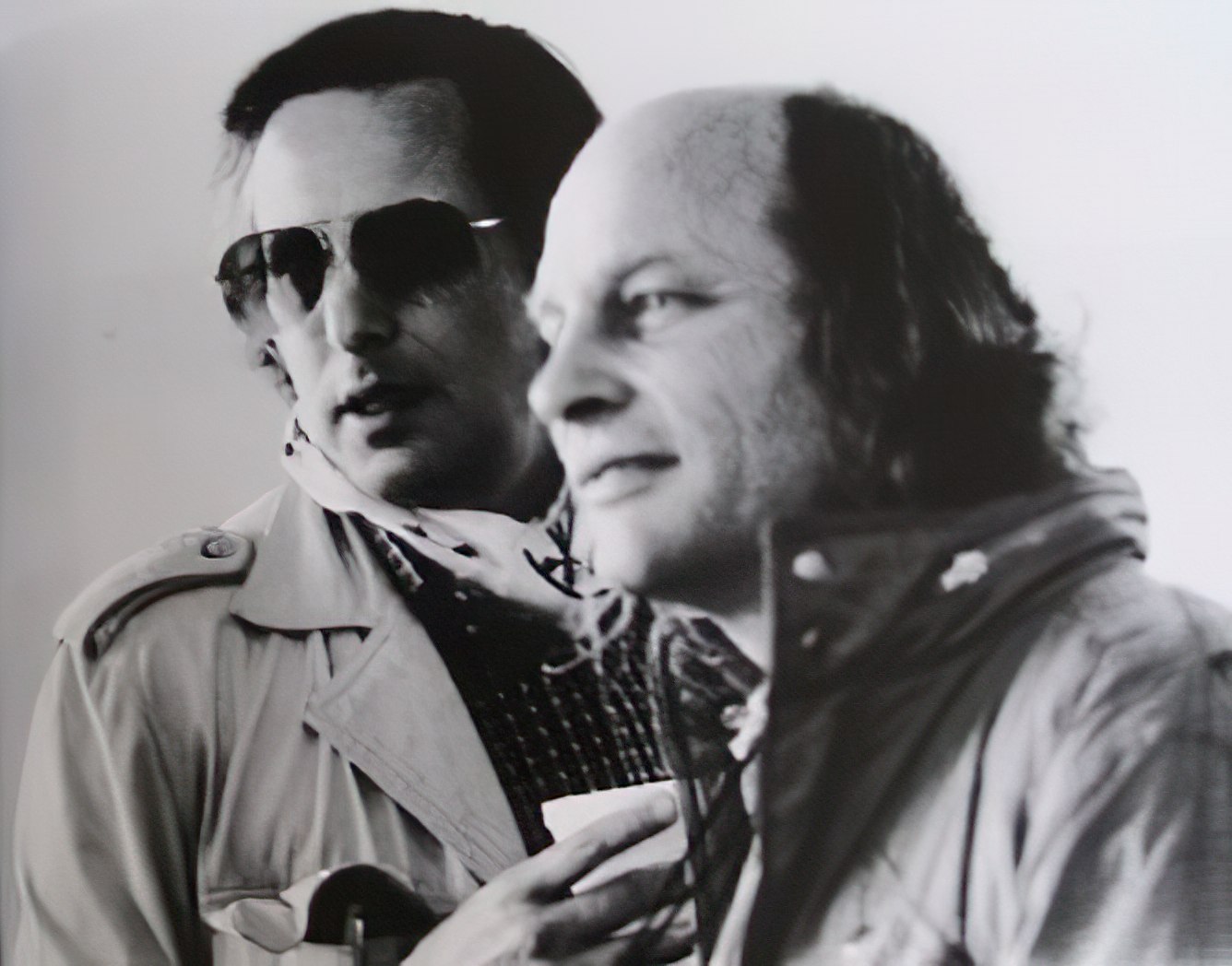

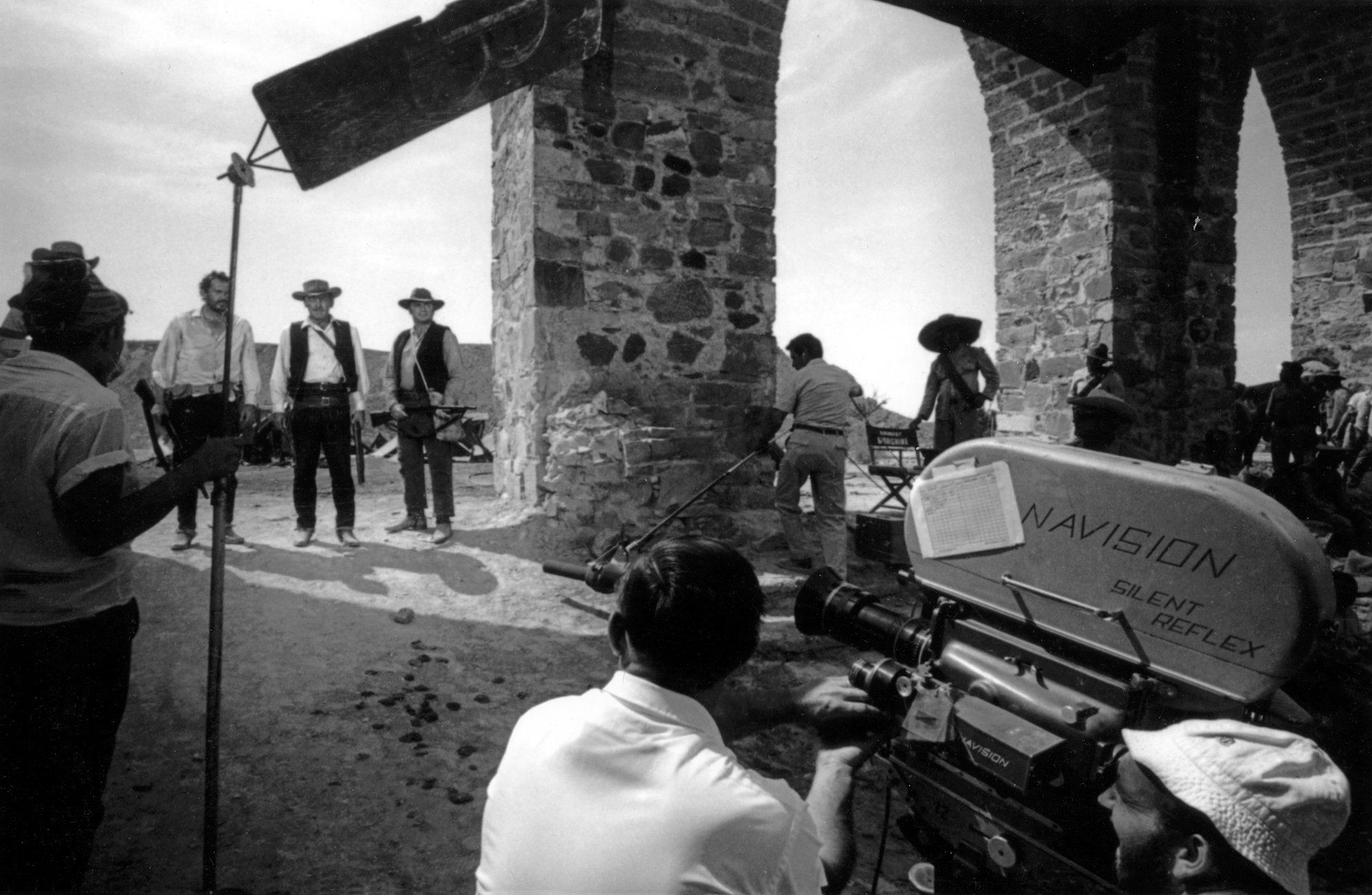

Here are several photos taken behind-the-scenes during production of William Friedkin’s Sorcerer. Production still photographer: N/A © Universal Pictures/Warner Bros. Home Entertainment. Intended for editorial use only. All material for educational and noncommercial purposes only.

Get Cinephilia & Beyond in your inbox by signing in